Developing Competency in Baccalaureate Nursing Education: Preparing Canadian Nurses to Enter Today’s Practice Environment

By Jodi Found RN,BSN,MN

SIAST Faculty / University of Regina Adjunct Professor

jodi.found@siast.sk.ca

A Special thanks to Dr.Norma Stewart for her mentorship and the SIAST Nursing Informatics Faculty Development Team for all the efforts towards furthering nursing informatics.

Abstract

Baccalaureate nursing education is not preparing graduates with adequate competencies to practice in today’s technology-rich health care environment. Competence in nursing informatics (NI) is lacking in students and faculty alike at local, national, and international levels. Faculty may be the biggest hindrance to this issue. A description of how one educational institution is developing strategies to increase their faculty capacity for NI using current evidence, theory, and perseverance is presented in this paper. It will also demonstrate the usefulness of having a NI competency list in order to measure student outcomes.

Baccalaureate nursing education is not preparing graduates with adequate competencies to practice in today’s technology-rich health care environment. Competence in nursing informatics (NI) is lacking in students and faculty alike at local, national, and international levels. Faculty may be the biggest hindrance to this issue. A description of how one educational institution is developing strategies to increase their faculty capacity for NI using current evidence, theory, and perseverance is presented in this paper. It will also demonstrate the usefulness of having a NI competency list in order to measure student outcomes.

The use of technology in health education has been described in the literature since the early 1970s. Current local and international literature reflects the urgency of establishing competent professionals that can practice in the ever-evolving, technology-rich health care environment. The emergence of the electronic health record (EHR), advances in hospital and clinical information systems, and the push to use evidence at the point-of-care in many countries have propelled this urgency for all nurses to become competent in areas enveloping technology and health.

Despite staggering amounts of data to support the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in nursing, there has yet to be any real action globally in baccalaureate nursing education to provide the health care system with beginner nurses ready to practice with skills, knowledge, and a positive attitude in nursing informatics (NI). Many nurse educators do not understand the scope of NI and they may be the biggest barrier to developing student competence in NI (Thompson & Skiba, 2008). Nurse educators must move beyond thinking that NI is simply using computers in nursing or posting a course online.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a clear, evidence-based definition of NI and rationale for why knowledge and skill in NI is important to the entry-level nurse in practice. As a nursing education example of this issue, I will present what commitment to building competence in NI looks like at a Western Canadian College and some challenges to consider. Perhaps our initiatives may inspire you or your organization to consider strategic steps to influence a global change in this crucial area of nursing education. The Diffusion of Innovation theory is suggested as a foundation to move ICT initiatives forward. I will argue that nurse educators must start with valuing competence in NI and working towards developing their own competence.

DEFINITION OF NURSING INFORMATICS

Nursing informatics

Thompson and Skiba (2008) report that many nurse educators do not know what NI entails and according to their critical review of the literature, Staggers and Bagley-Thompson (2002) define NI as integration of:

nursing science, computer science, and information science to manage and communicate data, information, and knowledge in nursing practice. Nursing informatics facilitates the integration of data, information, and knowledge to support clients, nurses and other providers in their decision making in all roles and settings. (p. 260)

It is important for nurse educators to understand that NI integrates three areas of knowledge and skills- nursing science, computer science, and information science. These will be further defined.

Nursing science

Barrett (2002) defined nursing science as “the substantive, discipline-specific knowledge that focuses on the human-universe-health process articulated in the nursing frameworks and theories” (p.57). Nursing is an evolving profession that continually develops knowledge to improve nursing practice. Skills and knowledge in nursing science will assist the nurse educator to integrate the nursing portion with the informatics piece. The nurse applies evidence from nursing science to improve client outcomes. The nurse educator must demonstrate to students how to apply evidence-based care.

Computer science

To be computer literate, according to the Committee on Information Technology Literacy (1999), requires skill and knowledge in computer science. Computer literacy is defined as the skill sets to be computer fluent, not only being able to manage a computer and use common software applications (e.g., e-mail, word processing, spreadsheets, and databases), but, also to know about computers and information systems, how they work and how they impact society. This definition implies having the ability to solve problems by reasoning, testing possible solutions, anticipating and adapting to change, and troubleshooting. Skills and knowledge in computer science are required for the nurse educator to function in today’s health care and education settings and to also develop these skills in students.

Information science

Information literacy has four components, according to the American Library Association Presidential Committee on Information Literacy (1989). These components are (1) the ability to recognize when information is needed, (2) locate, (3) evaluate, and (4) effectively use the needed information. Nurse educators must be proficient in this area in order to teach students how to effectively use information to improve patient care.

Nurse educators must understand what NI entails to be proficient in computer, information, and nursing science. Adept nurse educators have the capability to enhance student competency in NI. Only then can an educational institution present the health care system with a beginner level nurse that is competent in providing the best possible care to clients and communities.

LITERATURE REVIEW

NI and the Practicing Nurse

There is an array of literature to support the use of NI in nursing practice for the benefit of the patient, the nurse, and the health system. It is the goal of any educational institution to present the health system with a competent beginner nurse ready to practice in today’s health care setting.

Patients can be empowered when nurses employ their NI skills and knowledge (Vlasses & Smeltzer, 2007). Additionally, increases in accessibility (Canadian Nurses Association (CNA), 2006b; Dagnone, 2009), safety (Institute of Medicine (IOM), 1999; IOM, 2001) and quality of care (CNA, 2006b; CNA & Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions (CFNU), 2006) occurs when nurses use NI skills and knowledge. NI skills can also advance the nursing discipline (CNA, 2006a; Hannah, 2008; ICN, 2009a; Pringle & Nagle, 2009), can assist nurses in providing evidence-based care, promote a spirit of inquiry, critical thinking, and a philosophy of life-long learning (CNA, 2006b; CNA, 2006c; Hegarty, Condon, Walsh, & Sweeny, 2009; McNeil McNeil, Elfrink, Bickford, Pierce, Beyea, Averill, & Klappenbach, 2003; Nayda & Rankin, 2008; Sherwood & Drenkard, 2007). Finally, the health system can benefit by using technology to reduce costs and increase efficiencies (CNA, 2009; Smadu, 2008) and to help manage all the information (Rubenfield & Scheffer, 2006).

NI and the Nurse Educator

Much of the health literature, professional reports, and nursing position statements overwhelmingly support and encourage the use of informatics in nursing education (CNA, 2006a; CNA, 2006b; CNA, 2006c; Fetter, 2008; Hannah, 2007; Hebert, 1999; IOM, 1999; IOM, 2001; International Council of Nurses (ICN), 2009a; ICN, 2009b; Pringle & Nagle, 2009). Despite this, many nursing faculty are not prepared to integrate NI into curricula and consequently they interfere with the incorporation of technology into curricula. Nurse educators have been found to have low computer literacy skills (Austin, 1999; Nagle & Clarke, 2004; Ornes & Gassert, 2007; Saranto & Hovenga, 2004; Thompson & Skiba, 2008). Additionally, they feel they have enough skill in this area and do not seem to see the potential that NI skills can have on their students’ practice and in teaching and learning (Austin, 1999; McNeil, et al., 2003; McNeil, Elfrink, Bickford, Pierce, Beyea, Pierce, & Bickford, 2006; Nagle & Clarke, 2003; Ornes & Gassert, 2007; Saranto & Hovenga, 2004; Thompson & Skiba, 2008).

Education and training in NI has been demonstrated to increase the knowledge and confidence of students in NI, but training of faculty has yet to be studied. The majority of courses that had been offered to students only contained information on computer literacy and did not include information literacy components (Courey, Benson, Deemer, & Zeller, 2006; Verhey, 1999). Nurses are knowledge workers and competence in information science is vital to providing informed care. Nurses who self-reported competence in computer literacy skills were more likely to incorporate these skills in classes they were teaching (Austin, 1999; Thompson & Skiba, 2008). Very few schools of nursing are incorporating informatics competencies into their curricula (Booth, 2006; Nagle & Clarke, 2004; Ornes & Gassert, 2007; Thompson & Skiba, 2008). If faculty do not have NI skills and are not incorporating informatics competencies into their curricula, how do institutions intend on meeting the NI needs of graduates? The need to increase faculty capacity for NI is glaringly obvious.

Educators in the Classroom

Nurse educators are increasingly using technology in the classroom. In education, millennial students are hungry for technology (McCartney, 2004; Oblinger & Oblinger, 2010). Additionally, there is a push to provide more distributed learning opportunities for students. According to Porter O’Grady (2003) preparing new nurses requires different approaches. Some of these approaches may include the use of computers and knowledge in computer science, information science, and nursing science.

The literature, specifically for technology in education, is growing exponentially as teachers are demonstrating the benefits of technological tools to support education, such as use of electronic medical devices (EMDs) or personal digital assistants (PDAs), simulation, virtual worlds, Blogs, Wiki pages, and discussion boards to name a few. It is not the intent of this paper to look at each learning tool and the benefits in education; however, it is important to note that nurse educators and researchers are continually striving to engage their students in a more student-focused environment. Faculty require professional development in this area.

Educators in the Clinical Practice Setting

Educators continue to use the clinical setting as a main component of nursing education. Faculty and students are required to be more skilled and knowledgeable in the information systems used in these areas. Although Fetter (2008) found that the various information systems were problematic, Saskatchewan Institute of Applied Science and Technology (SIAST) is fortunate to deal with only one province-wide information system. Yet, there remains the challenge to get faculty orientated to these systems. There is disconnection between what the practice settings are doing and what educators have been prepared for.

Many professions, including nursing, are relying on wireless, handheld devices to provide the best evidence at the point-of-care. The Canadian Nurses Association and the USA’s National League of Nurses recommend the use of the PDAs to assist nurses in information retrieval (CNA, 2006b; NLN, 2008). The literature reveals many advantages of the use of these devices for students when caring for patients. There is greater accuracy and speed when students research their patient’s medication (Greenfield, 2007), improved student time-management (Guillot & Pryor, 2007; White, Allen, Goodwin, Breckinridge, Dowell, & Garvy, 2005), greater student satisfaction (Bauldoff, Kirkpatrick, Sheets, & Curran, 2008; Carlton, Dillard, Campbell, & Baker, 2007; Curran, 2008; Goldsworthy, Lawrence, & Goodman, 2006; Williams, & Dittmer, 2009), increase in student self-efficacy (Bauldoff, Kirkpatrick, Sheets, & Curran, 2008; Carlton, Dillard, Campbell, & Baker, 2007; Curran, 2008; Goldsworthy, Lawrence, & Goodman, 2006; Kuiper, 2008; Williams, & Dittmer, 2009), and reduction in medication errors by students and faculty (Guillot & Pryor, 2007). The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Canada report one out of ten Canadian patients are the product of a medication error and offer several technologies to prevent these accidents-the PDA was listed as one such device (2010).

In this information-age, nursing students and faculty are inundated with all kinds of information. Their primary tasks are that of communication, information retrieval and dissemination. Nursing students are required to make critical decisions based on the information they have. The use of the PDA at the bedside is the epitome of evidenced-based practice at point-of-care. Scollin, Healey-Walsh, Kafel, Mehta, and Callahan (2007) found that student’s perceptions and acceptance of the PDA were enhanced when there were faculty champions using the device. This further demonstrates the importance of faculty competence development in this area.

Additionally, billions of people around the globe are using a mobile device as their primary means for connecting to the internet and this is their only means (Rainie & Anderson, 2008). Nursing faculty that use mobile technology are embarking on a tool that appears to be here to stay. In fact it may be one way to achieve health in the most isolated and impoverished nations due to the interconnectivity and access to information the mobile device can provide.

Furthermore, patients are presenting with health knowledge due to increasing accessibility to information over the internet. Students and faculty must develop their information literacy skills to be able to evaluate all the information coming at them from various print and electronic resources and also assist their patients to evaluate various resources of information. According to McLeod and Mays (2008), “the challenge for teachers is to empower students to navigate evaluate, select, and synthesize information to support real-time, evidenced-based practice at the point of care” (p.584).

Finally, students need to be aware that their discipline and their patients rely on the data collected by nurses. Students need to make the connection that patient data provides knowledge to measure nursing sensitive outcomes. Faculty and nurse students also have the additional responsibility to protect patient’s electronic information and must have skill and knowledge to be competent and ethical.

NURSING INFORMATICS AS A FOUNDATION COMPETENCY

In Canada, nurses are guided by foundational standards set out by their provincial regulatory bodies and the Canadian Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses (CNA, 2008). Although many provinces recently added a number of new competencies to keep up with the explosion of information and technology, perhaps they have not been explicit enough in requiring more NI competencies as a foundation to practice. A foundation competency “is the knowledge, skill, and judgment derived from nursing roles and functions, within a specified context, at the completion of an approved nursing education program leading to registration and licensure as a registered nurse” (Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association [SRNA)] 2007, p.4). These are minimum competency levels, below which registered nurse performance is unacceptable. The SRNA adds that each nurse is accountable for his/her own competence and is responsible to obtain these competencies. The ICN echoes this professional responsibility (2009c).

Canadian regulatory bodies have put the ownership on each individual RN to stay competent and current. However, a recent media release (May, 2011) suggests that Canada Health Infoway and the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN) are partnering to create a resource for faculty and students over the next three years. Educational institutions can look forward to this resource that will “focus on the development, evaluation, and sharing of curriculum-based resources and e-learning tools” (Canada Health Infoway, 2011). If this resource is three years out that means starting in 2015 will produce a competent graduating nurse in 2019 for most programs. Education cannot wait for this resource.

The e-Nursing strategy for Canada recommends “supporting the development and implementation of NI competencies among the competencies for required entry-to-practice and continuing competence” (CNA, 2006b, p.5). However, no formal list of competencies has been provided by this organization. Fetter (2008) from the United States of America (USA) also describes establishing and documenting minimal competencies as an IT priority. One can refer to the USA’s Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER) and Quality and Safety Education (QSEN) initiatives to reveal some of this work which has a real focus on patient safety. The need for ongoing ICT development was also noted in Australia (Smedley, 2005) and by others globally in Taiwan (Chang, Gassert, & Curran, 2011; Cho & Chang, 2009) and Finland (Saranto & Hovenga, 2004).

Professional practice, according to the CNA (2011), requires the RN to “practice in a manner that is consistent with the values of the Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses (2008)”. A nurse who is not aware of the tools to protect electronic health information, for example, is not functioning ethically. Educational institutions need to be accountable for teaching these skills and practicing nurses need to be professional and ethical.

NI COMPETENCIES FOR NURSE EDUCATORS

Staggers, Gassert, and Curran (2001) defined nursing informatics competencies as the integration of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in the performance of various nursing informatics activities within the prescribed levels of nursing practices” (p.309). Although there is a few other competency lists presented in the nursing literature (Grobe, 1988; McCanon & O’Neal, 2003; McNeal & Odom, 2000), the list of NI competencies by Staggers, Gassert, and Curran (2001, 2002) was based on a comprehensive literature review from 1986 to 1998. They received input from NI experts in the USA and following a two-round Delphi study developed 281 NI competencies for four levels of practicing nurses.

SIAST’S ADAPTATION OF A NI COMPETENCY LIST

In 2006, SIAST established an Informatics Project team to undertake activities to advance the concept of NI within nursing education. This team was further divided into working groups. The faculty development working group recently reviewed and updated Staggers, Gassert, and Curran’s (2001, 2002) list of competencies, considering the year and context. We cross-tabulated the list with several other published lists (Grobe, 1988; McCanon & O’Neal, 2003; McNeal & Odom, 2000) and found it to be inclusive. In establishing a competency list an organization can begin to measure faculty outcomes. For instance, faculty could report on 3-point Likert scale if they are beginner, novice or experienced in any one of the competencies. An organization could use this list for staff orientation, professional development, performance appraisal, and for quality improvement initiatives. Additionally, NI competencies can be used to guide curriculum. According to the SRNA (2007), the standards also provide a way to account legally, publicly, and professionally.

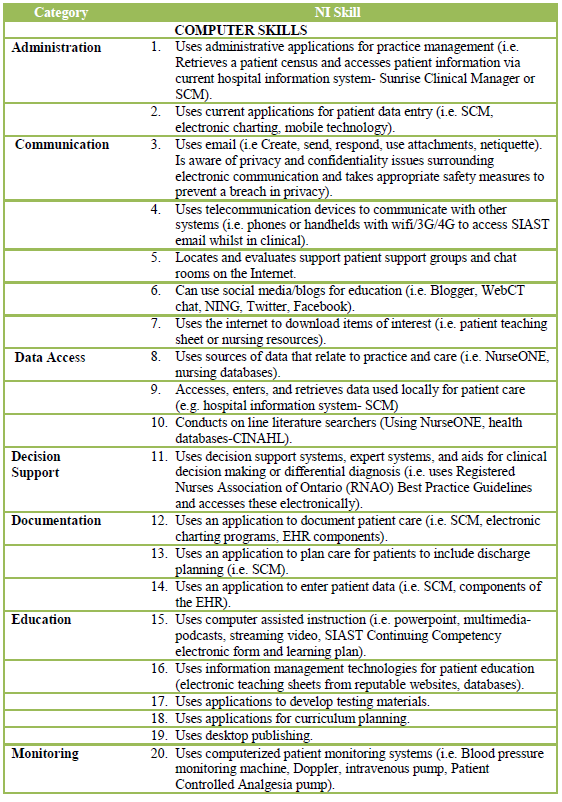

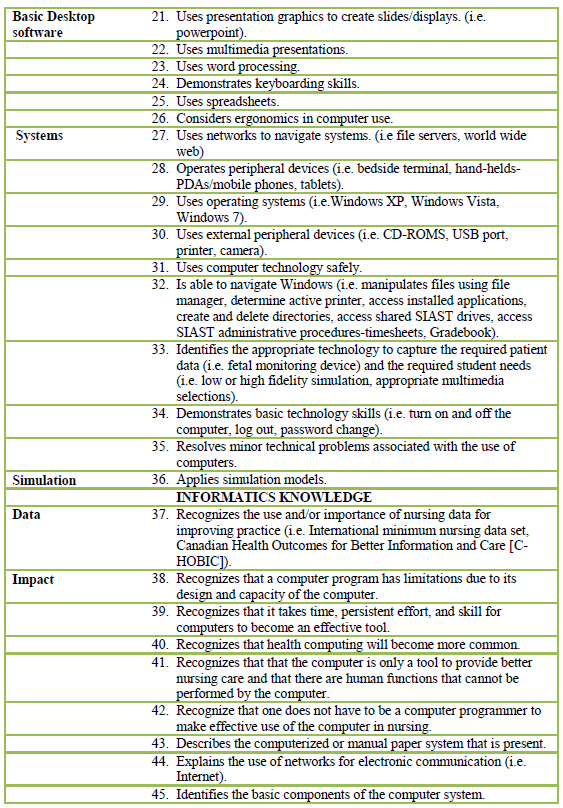

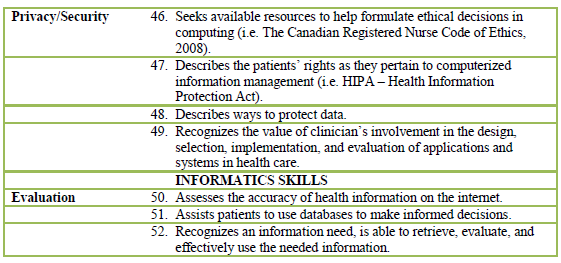

Please refer to Table 1 for the list of adapted NI competencies for nurse educators.

Table 1: Nursing Informatics Competencies for Baccalaureate Nurse Educators

Table 1: Nursing Informatics Competencies for Baccalaureate Nurse Educators |

Adapted from Staggers, Gassert, and Curran (2001, 2002).

Copyright permission pending.

FACULTY DEVELOPMENT FOR NI COMPETENCY UPTAKE

Rogers (1985) synthesized research from several hundred diffusion studies and produced the Diffusion of Innovations Theory for individuals and organizations. According to Rogers, faculty will go through five stages in a process of adoption of an innovation over time. There is a knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation stage.

In the exemplar educational institution, the NI faculty development team was dedicated to increasing the knowledge and awareness of NI for faculty. This team assessed the literature and current faculty knowledge, skills, and attitudes in NI. We developed a vision, brainstormed and prioritized several innovative ideas which all contributed to a shared strategic plan. To increase faculty awareness, NI was on the agenda for each monthly faculty meeting. Local experts provided ‘show and tell’ presentations of new classroom technologies. Additionally, we email a quarterly eNewsletter to all faculty with information on NI resources, links, recent articles, information on upcoming conferences, and a call for volunteers to join the team. Posters were strategically placed around campus, a Peer-to-Peer network was established where faculty volunteered their name and services on certain technologies that they had tried and felt comfortable using. A website was set up using our local system software as ‘the’ place faculty could go for resources and links. The team also collaborated and networked with local resources and programs. Additionally, the team collaborated with outside stakeholders such as other educational institutions, government, clinical agencies, technology vendors, and experts in the field. All of these strategies could be considered part of the knowledge and persuasion stages of innovation diffusion.

According to Rogers (1985), the individual then goes through a decision and implementation phase. To assist faculty in these stages, we recommended resources for faculty. The team reviewed and recommended one of two national informatics development programs. Also, resources were recommended in eNewsetters, posters, and the webpage for faculty to complete their annual continuing competence learning plans per professional requirements. Additionally, our local information technology (IT) staff made themselves available for 1:1 time with faculty.

Confirmation is the final stage of innovation diffusion (Rogers, 1985). Our project team is in the planning stage of developing a competence tool based on the adapted competency list provided in Table 1. This will allow our institution to measure outcomes of our initiatives and individual faculty endeavours to build capacity for NI.

Roger’s theory also classifies individuals into five categories-innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards (1985). Reflecting on this theory reveals the importance of time and the creation of a culture that is sensitive to individuals that may be the late majority or the laggard category. By applying this theory and allowing the individuals in the organization to adopt the innovation in their own time frame, a culture in the organization is created that respects individual differences and values individual decisions.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

There are a host of challenges to consider in the development of nurse educator NI competency. As mentioned earlier, many faculty do not know what NI is and, therefore, do not have the understanding necessary to acknowledge it’s importance in undergraduate education. Additionally, many current nurse educators were not required to work with a computer until recently. The majority of permanent faculty in Canada are in the 50+ age cohort (CNA, 2010) and have not been provided education themselves on NI. According to Nagle (2005), without advanced education in NI (i.e. graduate level), there will be too few nurses who are able to advance and understand the agenda of eHealth for all. Faculty preparation is urgently needed to graduate competent practitioners.

Another challenge is that twenty-one percent of full time Canadian faculty are engaged in academic upgrading programs themselves-mostly graduate programs (CNA & CASN, 2010). Although this appears to be a barrier due to faculty lack of time for additional NI training, it may prove beneficial as more master and doctoral students are focusing their work in NI.

An increasing number of students have further increased the load on existing faculty. According to the CNA’s most recent Education Statistical Report(2008/09), the number of students admitted into Canadian educational programs has almost doubled from 8,947 in 1999 to 14,010 in 2008/09 with Ontario and Saskatchewan seeing the most substantial increases (CNA, 2010). Rising student numbers is taking a toll on faculty. Feedback from our own faculty revealed lack of time as the main reason that faculty does not engage in NI competency development.

Resistance to change is common and institutions need to look at their culture and develop strategies to deal with ongoing change. The Diffusion of Innovation Theory is one theory that can provide a theoretical foundation to assist with development of NI competencies. Strong leadership in NI and perhaps hiring of dedicated faculty could assist in sustaining initiatives.

SUMMARY

A clear definition of NI and a faculty that see the value and urgency of establishing a propensity in foundational NI competencies will be better prepared to move to action. An NI competent teacher knows what NI entails and knows the value of NI in today’s health care arena locally and globally. This teacher is better prepared to develop these competencies in student nurses which will present the health care system with beginner nurses ready to practice.

I have demonstrated how one institution’s journey can help to increase faculty competence in NI; however, it is only through outcomes measurement that we will know if we achieved success in this venture! A list of nurse educator competencies can be the road map to help guide an institution on this journey.

CONCLUSION

It is long overdue that baccalaureate nursing education be responsive to the needs of its society, health care environment, patients and students. If nurse educators around the world develop competency in NI, they will be better prepared to provide graduate students the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitude to function in this decade and beyond. Through ongoing efforts and supportive leadership an educational institution can begin to meet the demands of the requirements of a beginner nurse in this technology enriched environment.

By creating faculty and student objectives from a list of competencies, outcomes of both faculty and students can be measured over time and assist the institution to provide evidence for future development. In this way, education is contributing to advancing the discipline in its use of data to create information which in turn creates knowledge. It is only through this process of knowledge generation that strategic planning can take place to improve the quality of nurse education for the overall goal of improved patient care. It is time for individual faculty and educational institutions to make the commitment to develop competence in NI.

REFERENCES

Austin, S. I. (1999). Baccalaureate nursing faculty performance of nursing computer literacy skills and curriculum integration of these skills through teaching practice. Journal of Nursing Education, 38(6), 260-266.

Barrett, E.A.M. (2002). What is nursing science? Nursing Science Quarterly, 15(1), 51-60.

Bauldoff, G.S., Kirkpatrick, B., Sheets, D.J., & Curran, C.R. (2008). Implementation of handheld devices. Nurse Educator, 33(6), p.244-248.

Booth, R. G. (2006). Educating the future eHealth professional nurse. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 3(1), 1-10.

Canada Health Infoway. (2011). Education of next generation of nurses to include effective use of information and communication technologies. Retrieved from https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/lang-en/about-infoway/news/news-releases/732

Canadian Nurses Association(CNA) & Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN). (2010). Nursing education in Canada statistics 2008-2009. Registered Nurse workforce, Canadian production: Potential new supply. Retrieved from http://www.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/Education_Statistics_Report_2008_2009_e.pdf

Canadian Nurses Association & Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions (CFNU). (2006). Practice environments: Maximizing client, nurse and system outcomes [Joint Position Statement]. Retrieved from, http://www.cna-aiic.ca.

Canadian Nurses Association (2010). 2008 Workforce profiles of Registered Nurses in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.cna-nurses.ca/CNA/nursing/statistics/default_e.aspx

Canadian Nurses Association (2011). Canadian Registered Nurse examination: Competencies. Retrieved from http://www.cna-nurses.ca/CNA/nursing/rnexam/competencies/default_e.aspx

Canadian Nurses Association. (2006a). Better health care, better patient outcomes: An E-nursing strategy. Retrieved from http://www.cna-nurses.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/E-Nursing-Strategy-2006-e.pdf

Canadian Nurses Association. (2006b). E-Nursing Strategy for Canada. Retrieved from http://www.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/E-Nursing-Strategy-2006-e.pdf

Canadian Nurses Association. (2006c). Nursing information and knowledge management. [Position Statement]. Retrieved from http://www.cna-nurses.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/PS87-Nursing-info-knowledge-e.pdf

Canadian Nurses Association. (2008). Code of ethics for Registered Nurses. Retrieved from http://www.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/Code_of_Ethics_2008_e.pdf

Carlton, K.H., Dillard, N., Campbell, B.R., & Baker, N. (2007). Personal digital assistants in the classroom and clinical areas. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, September/October

Chang, J., Poynton, M.R., Gassert C.A, Staggers, N. (2011). Nursing informatics competencies required of nurses in Taiwan. International Journal of Medical Informatics ,80(5), 332-40.

Cho, C.S., & Chang, P. (2009). Using change theory to examine the nursing informatics development in Taiwan. Studies in Health and Technology Informatics, 146, 871-73.

Committee on Information Technology Literacy. (1999). Being Fluent with Information Technology.Washington, D.C: National Academy Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=6482

Courey, T., Benson-Soros, J., Deemer, K., & Zeller, R. A. (2006). The missing link: Information literacy and evidence-based practice as a new challenge for nurse educators. Nursing Education Perspectives, 27(6), 320-323.

Curran, C. ( 2008). Faculty development initiatives for the integration of informatics competencies and point-of-care technologies. Nurse Clinics of North America, 43, p.523-533.doi: 10.1016.cnur.2008.06.001

Dagnone, T., (2009). For patient’s sake: Commissioners recommendations. Saskatchewan’s patient-first review report. Retrieved from, http://www.health.gov.sk.ca/adx/aspx/adxGetMedia.aspx?DocID=79bf4a96-ff32-486d-b4ab-c0d2d4d42922&MediaID=3332&Filename=patient-first-recommendations.pdf&l=English

Fetter, M. 2008. Enhancing baccalaureate nursing information technology outcomes: faculty perspectives. [Serial Online]. International Journal of Education Scholarship, 5(1), 1-15.

Goldsworthy,S., Lawrence, N., Goodman, W. (2006). The use of personal digital assistants at the point of care in an undergraduate nursing program. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 24(3), p. 138-143.

Greenfield, S. (2007). Medication error reduction and the use of PDA technology. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(3), p. 127-131.

Grobe, S.J. (1988). Nursing informatics competencies for nurse educators and researchers. In H. Peterson & U. Gerdin-Jelger (Eds.) Preparing Nurses for Using Information Systems: Recommended Informatics Competencies, New York: National League for Nursing. 25-40; 117-138.

Guillot, L., & Pryor, S. (2007). PDA use by undergraduate nursing students on pediatric clinical rotations. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 7(3), p.13-20.

Hannah, K. (2008). Health Informatics and Nursing in Canada. HCIM & C, 12(3), 45-51. Retrieved from http://www.healthcareimc.com/bcovers/previous/Vol_XIX_No_3/pdfs/Vol_XIX_No_3_7.pdf

Hannah, K. J. (2007). The state of nursing informatics in Canada. Canadian Nurse, 103(5), 18.

Hebert, M. (1999). Discussion paper. National nursing informatics project. Canadian Nurses Association. Ottawa: author.

Hegarty, J., Condon, C., Walsh, E., & Sweeney, J. (2009). The undergraduate education of nurses: Looking to the future. International Journal of Scholarship, 6(1), 1-11.DOI: 10.2202/1548-923X.1684

Institute of Medicine (IOM). 1999. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

International Council of Nurses (ICN). (2009a). Guidelines for ICNP catalogue development. Retrieved from http://www.icn.ch/pillarsprograms/icnpr-catalogues/

International Council of Nurses. (2009b).What is nursing informatics? Retrieved from, http://www.icn.ch/matters_informatics.htm

International Council of Nurses. (2009c). Continuing competence as a professional right and public responsibility [Position Statement]. Retrieved from http://www.icn.ch/images/stories/documents/publications/position_statements/B02_Continuing_Competence.pdf

Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). (2007). Using PDAs to reduce medication errors. Retrieved online from http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/nursing/Issues/NurseAdviseERR200708.pdf

Kuiper, R. (2008). Use of personal assistants to support clinical reasoning in undergraduate baccalaureate nursing students. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 26(2), p.90-98.

McCanon, M, & O’Neal, P.V. (2003). Results of a national survey indicating information technology skills needed by nurses at time of entry into the workforce. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(8), 337-340.

McCartney, P. 2004. Leadership in nursing informatics. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological, and Neonatal Nursing, 33(3), 371-380.

McLeod, R.P., & Mays, M.Z. (2008). Back to the future: Personal digital

assistants in nursing education. Nursing Clinics of North America, 43

(4): 583-92.

McNeal, B.J., & Odom, S.K. (2000). Nursing informatics education in the United States: Proposed undergraduate curriculum. Health Informatics Journal, 6, p. 32-38.

McNeil, B.J., Elfrink, V.L., Bickford, C.J., Pierce, S.T., Beyea, S.C., Averill, C., & Klappenbach, C. (2003). Nursing information technology knowledge, skills, and preparation of student nurses, nursing faculty, and clinicians: A U.S. survey. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(8), 341-349.

McNeil, B.J., Elfrink, V.L., Bickford, C.J., Pierce, S.T., Beyea, S.C., Pierce, S.T., & Bickford, C.J. (2006). Computer literacy study: report of qualitative findings. Journal of Professional Nursing, 22(1), 52-9.

Nagle, L. (2005). Focus on Leaders. Dr.Lynn Nagle and the case for nursing informatics. Nursing Leadership, 19(1), 16-18.

Nagle, L., & Clarke, H. (2003). Educating tomorrow’s nurses: Where is nursing informatics? Retrieved from http://www.cnia.ca/OHIHfinaltoc.htm

Nagle, L., & Clarke, H. (2004). “Assessing Informatics in Canadian Schools of Nursing.” Proceedings 11th World Congress on Medical Informatics, San Francisco, CA.

National League for Nursing (NLN). (2008). Preparing the next generation of nurses to practice in a technology-rich environment: An informatics agenda [Position Statement]. Retrieved from http://www.nln.org/aboutnln/PositionStatements/index.htm

Nayda, R. & Rankin, E. (2008). Information literacy skill development and life long learning: Exploring nursing students’ academics’ understandings’. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 127(2), 27-33.

Oblinger, D., & Oblinger, J. (2010). Is it age or IT: First Steps Toward Understanding the Net Generation. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/Resources/EducatingtheNetGeneration/IsItAgeorITFirstStepsTowardUnd/6058

Ornes, L. L., & Gassert, C. (2007). Computer competencies in a BSN program. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(2), 75-78.

Porter-O’Gady, T. (2003). A different age for leadership, part 1: New context, new content. Journal of Nursing Administration, 33, 105-110.

Pringle, D. & Nagle, L. (2009). Leadership for the information age: The time for action is now. Electronic Healthcare, 8(1). Online Exclusive 2009. Retrieved from http://www.longwoods.com/product.php?productid=20849&cat=601&page=1

Rainie, L., & Anderson, J. (2008). The future of the internet III. Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2008/The-Future-of-the-Internet-III/4-Scenario-1-The-Evolution-of-Mobile-Internet-Communications/1-Prediction-and-Reactions.aspx

Rogers, Everett M. (1983). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

Rubenfeld, M.G., & Scheffer, B.K. (2006). Critical thinking tactics for nurses: Tracking, assessing, and cultivating thinking to improve competency-based strategies. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett.

Saranto, K., & Hovenga, E. J. S. (2004). Information literacy – What it is about? International Journal of Medical Informatics, 73(6), 503-513.

Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association. (2007). Standards and Foundational Competencies for the Practice of Registered Nurses. Retrieved from http://www.srna.org/images/stories/pdfs/nurse_resources/standards_competencies.pdf

Scollin, P., Healey-Walsh, J., Kafel. K., Mehta, A., & Callahan, J. (2007). Evaluating students’ attitudes to using PDAs in nursing clinicals at two schools. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, July/August, p.228-235.

Sherwood, G., & Drenkard, K. (2007). Quality and safety curricula in nursing education: Matching practice realities. Nursing Outlook, 55(3), 151-155.

Smadu, M. (2008). Review of the 10-year plan to strengthen health care. House of Commons. Standing Committee on Health. Ottawa: Canadian Nurses Association. Retrieved from http://www.cna-aiic.ca/cna/documents/pdf/publications/review_10_year_plan_e.pdf

Smedley, A. (2005). The importance of informatics competencies in nursing: An Australian perspective. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 23(2), 106-110.

Staggers, N., & Bagley Thompson, C. (2002). The evolution of definitions for nursing informatics. Journal of American Informatics Association, 9, 255-261. DOI 10.1197/jamiaM0946.

Staggers, N., Gassert, C. A., & Curran, C. (2001). Informatics competencies for nurses at four levels of practice. Journal of Nursing Education, 40(7), 303-316.

Staggers, N., Gassert, C. A., & Curran, C. (2002). A delphi study to determine informatics competencies for nurses at four levels of practice. Nursing Research, 51(6), 383-390.

The American Library Association’s Presidential Committee on Information Literacy. (1989). Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential.cfm

Thompson, B. W., & Skiba, D. J. (2008). Informatics in the nursing curriculum: A national survey of nursing informatics requirements in nursing curricula. Nursing Education Perspectives, 29(5), 312-317.

Verhey, M. P. (1999). Information literacy in an undergraduate nursing curriculum: Development, implementation, and evaluation. Journal of Nursing Education, 38(6), 252-259.

Vlasses, F., & Smeltzer, C. (2007). Toward a new future for healthcare and nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Administration, 37(9), 375-380.

White, A., Allen, P., Goodwin, L., Breckinridge, D., Dowell, D., & Garvy, R. (2005). Infusing PDA technology into nursing education. Nurse Educator, 30(4), p.150-154

Williams, M., & Dittmer, A. (2009). Textbooks on tap: Using electronic books housed in handheld devices in nursing clinical courses. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(4), p. 220-225.

BIO

SIAST Faculty / University of Regina Adjunct Professor

Saskatchewan Collaborative Bachelor of Science in Nursing (SCBScN) Program

Nursing Education Program of Saskatchewan (NEPS)

Saskatchewan Institute of Applied Science and Technology (SIAST)

Wascana Campus

4500 Wascana Parkway PO Box 556

Regina, SK, Canada S4P 3A3 Ph: 306.775-7616 | Fax: 306.775.7992

EDITOR: June Kaminski