Towards an Empirical Definition of Graduate School Healthcare Informatics

by Thomas Virgona, PhD

Assistant Professor

Adelphi University

New York

ABSTRACT

Background: Healthcare informatics is a relatively new field to academia. As with all new innovations, there may be some time before the Health Informatics discipline has a firm foothold on a definition.

Purpose: The purpose of this pilot study was to start to define the cross-disciplinary nature of a Healthcare Informatics graduate degree.

Method: For this study, a content analysis of courses in a Healthcare Informatics graduate degree program was conducted, using a representative sample of universities. The design goal was to construct a sample frame that corresponds to the population (Universities / Colleges).

For this pilot study, six universities were selected as a representative sample of Healthcare Informatics graduate programs.

The literature review of graduate programs in Healthcare Informatics shows the programs to be multi-disciplinary in nature.

Findings: After performing content analysis on the 120 courses from the 6 institutions, the findings do indicate Healthcare Informatics is a multi-disciplinary field.

Introduction

Healthcare informatics is a relatively new field to academia. As with all new innovations, there may be some time before the Health Informatics discipline has a firm foothold on a definition. Although healthcare informatics has spurred many unique degree names, all agree the field is multi-disciplinary in nature. In a new school or program, there may not be any standardized curricula or set course syllabi, which leaves considerable room for creativity and flexibility (HD Covvey, 2001). Oregon Health & Science University has developed a program that includes the full spectrum of courses, allowing education to be tailored to career goals and needs (Hersh, 2007). Although the field of health informatics encompasses many established disciplines, the field itself is still in a formative state that allows for teaching and curriculum development in a way that may not be possible in more established educational programs. It is difficult to talk of informatics education since the groups that need education in this field are not very homogeneous (Arie Hasman, 2000).

Graduate degree addressing healthcare informatics goes by many names;

- Bioinformatics

- Health Information Technology

- Health Management Information Systems

- Health Informatics

- Public Health Informatics

- Medical Informatics

- Consumer health informatics

Regardless of the health domain, all informatics subspecialties apply the informatics pyramid; (White, Jun/Jul 2013).

- The relationship and transformation of data.

- Information and knowledge, to making decisions and solving problems.

This pilot study was performed to add clarity to the multi-disciplined nature of Healthcare Informatics.

Literature Review

Research found Healthcare Informatics course development have included the following disciplines; business, legal, chemical informatics, bioinformatics, new media, copyright, trademark and patents (HD Covvey, 2001). The science of informatics has driven innovation in biomedical research, clinical care, and public health (CAHIIM, 2014). While each Healthcare Informatics program has specific targeted academic goals and audiences, there is overlap and some confusion related to the new field. Until recently, medical informatics focused on developing applications for health professionals – through the eyes of health professionals rather than through the eyes of patients. Today, medical informatics is “the field that concerns itself with the cognitive, information processing, and communication tasks of medical practice, education, and research” (Eysenbach, 2000, p. 1713).

With the diversity of approaches within health informatics, research is looking to define where appropriate relationships exist among information sciences, information technology and informatics. (Dalrymple, 2013). Today, health informatics professionals contribute to: (AMIA, 2014)

- Moving basic research findings from bench to bedside;

- Evaluating interventions across communities;

- Assessing the impact of health innovations on health policy; and

- Advancing the field of informatics.

The health informatics focus is changing towards usability, specifically for consumers. Currently, healthcare workers view clinical informatics in discrete pieces (Reese, May 2012). Health informatics is not restricted to the use of computers and telecommunications but also includes the delivery of information to patients through other media. The computer may not always be the most effective medium for delivering information, especially in dealing with elderly or injured patients (Eysenbach, 2000). Public Health Informatics (PHI) leverages information and computer science to support public health goals and decision-making while defining the science behind the technology (White, Jun/Jul 2013). PHI utilizes a range of disciplines, including information science, engineering, law and the social sciences (Savel, 2012). Discussions are now focused on developing and evaluating methods and applications to integrate consumer needs and preferences into information management systems in clinical practice, education, and research.

Health informatics education started in the 1960s, primarily in medical schools across the USA and Europe. By 1989 health informatics education had grown in more than 20 countries on five continents (Hovenga, 2000). In 1999, Indiana University created a new school, the School of Informatics, representing a wide range of disciplines (Hook, 2003). All health informatics programs are unique in terms of content and structure – reflecting many foundation disciplines.

The evidence suggests a poor uptake of informatics by the nursing profession (Hovenga, 2000). One contributing factor is the lack of a standardized nursing terminology. In order for the informatics goal of full interoperability across nursing information systems to be realized, this problem must be addressed (Schwirian, 2013).

The Commission on Accreditation for Health Informatics and Information Management Education (CAHIIM) is an independent accrediting organization that enforces quality Accreditation Standards for Health Informatics and Health Information Management (HIM) educational programs. (CAHIIM, 2014) An academic program in health informatics needs to include:

- Information Systems curriculum components focused on such issues as information systems analysis, design, implementation, management and leadership.

- Informatics curriculum components concerned with the study of structure, function and transfer of information, socio-technical aspects of health computing, and human-computer interaction.

- Information Technology curriculum components focused on computer networks, database and systems administration, security, and programming.

- Nurses must be supported consistently in their use of standardized nursing terminologies;

- Cross-mappings among the various terminologies must be completed.

Clearly healthcare informatics graduate program are in their formative state. A review of the literature that describes the growth of these programs indicates the varied nature of the programs:

- multi-disciplinary

- full spectrum

- tailored

- diversity

- include curriculum components from all three facets

Despite the agreement on the growth and the multi-disciplinary nature of the discipline, there has not been an effort to define what the spectrums of courses that comprise a healthcare informatics degree are or should be.

Research Methodology

Research purpose and questions

The purpose of this pilot study was to start to define the cross-disciplinary nature of a Healthcare Informatics graduate degree. Researchers in the field agree that the discipline includes a full spectrum of courses, but the diversity of courses remains vague. Consequently, many prospective students are confused by the goals of the degree

- What courses comprise a Healthcare Informatics graduate degree?

- What disciplines contribute courses/curriculum to the Healthcare Informatics graduate degree programs?

Methodology

For this study, a content analysis of courses in Healthcare Informatics graduate degree programs was conducted, using a representative sample of universities. The design goal was to construct a sample frame that corresponds to the population (Universities / Colleges) (Fowler, 2002).

Content analysis requires two processes: definition of the content characteristics (basic content elements) being examined and application of rules for identifying and recording these characteristics. An objective coding scheme must be applied to the courses (Berg, 2001). For this pilot study, each course was placed into an academic discipline. Four disciplines were selected for this study; Business (BUS), Healthcare (HC), Information Systems (IS) and Healthcare Informatics (HCI).

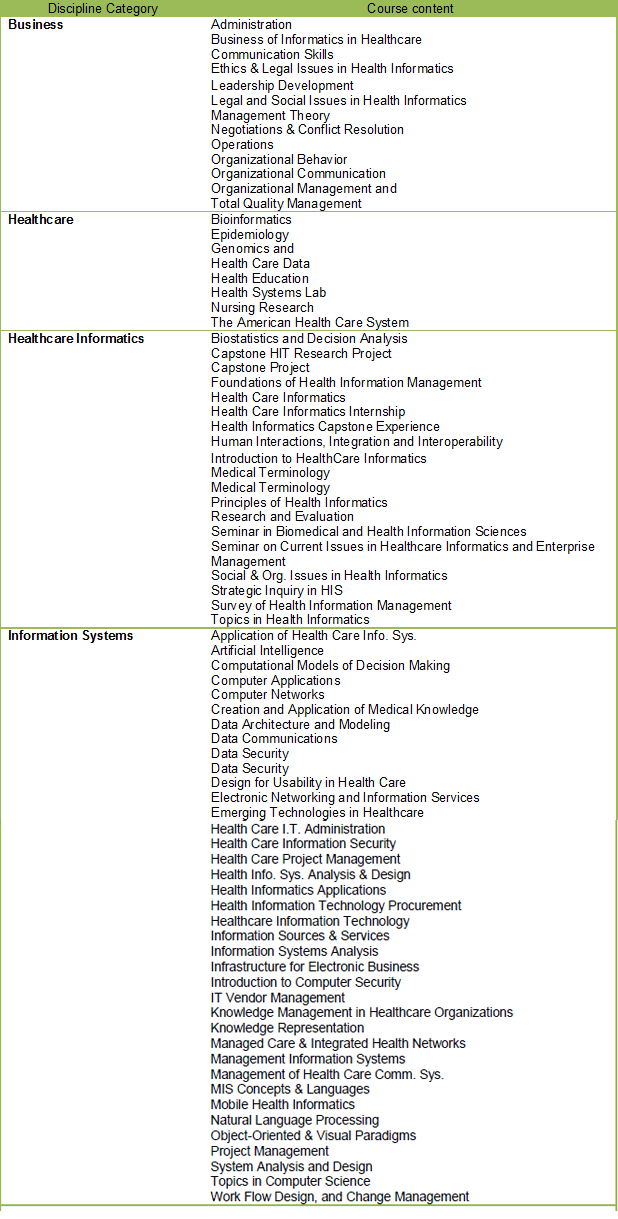

The guidelines for identifying a discipline for each category are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Content analysis components according to discipline

One design issue is how well the sample frame corresponds to the population a researcher wants to describe (Fowler 1993). Is this a true picture? By using a reprehensive sample, the goal was that the information derived from the sample and the conclusions reflected the same conditions that exist in University settings as a whole (Glebocki, 1984). Specifically excluded from the sample was “for-profit universities”, defined as colleges that are owned and operated by businesses and are ultimately accountable by law for the returns they produce for shareholders. (Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, 2014).

The sample selected for this pilot study (conducted in January 2014) included one university that is:

- Online

- Traditional

- Public

- Private

- Large School

- Small School

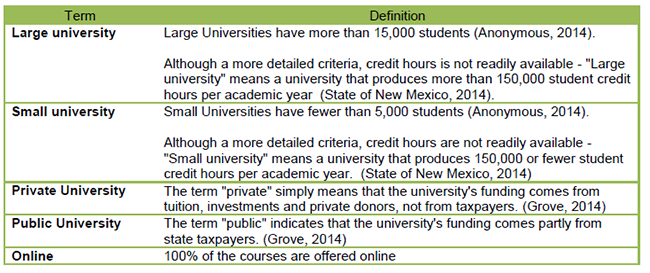

The following working definitions for this study were used (Table 2):

Table 2: Working Definitions

Research Findings

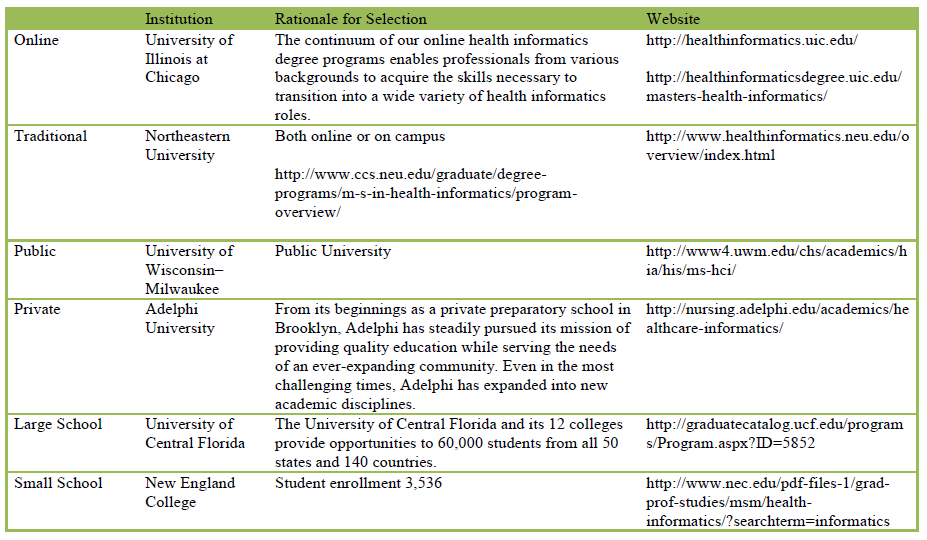

For this pilot study, six universities were selected as a representative sample of Healthcare Informatics graduate programs. The six universities are described in Table 3.

Table 3: Representative Sample Universities

(Right click and View Image for full size)

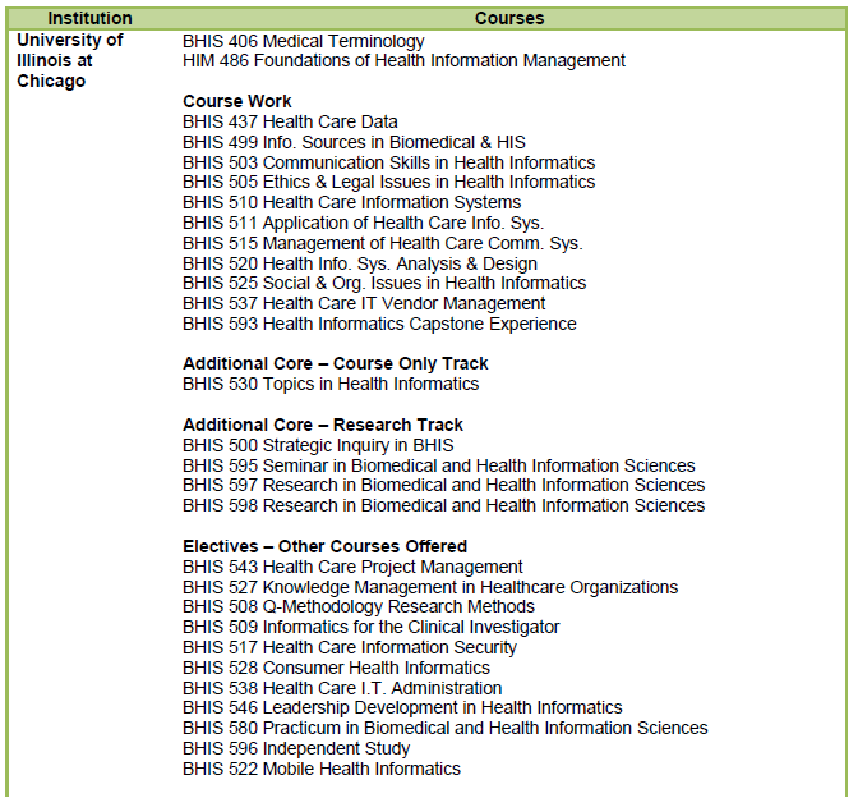

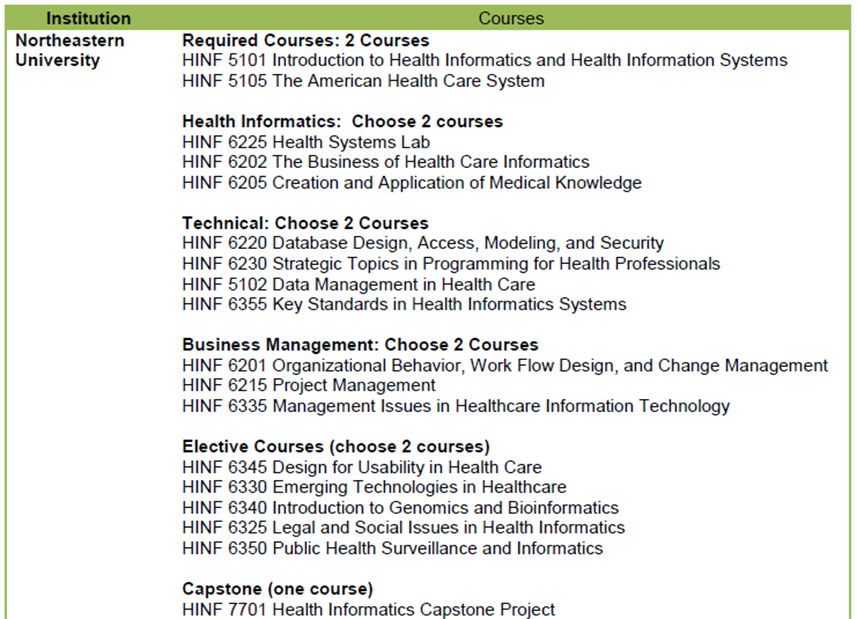

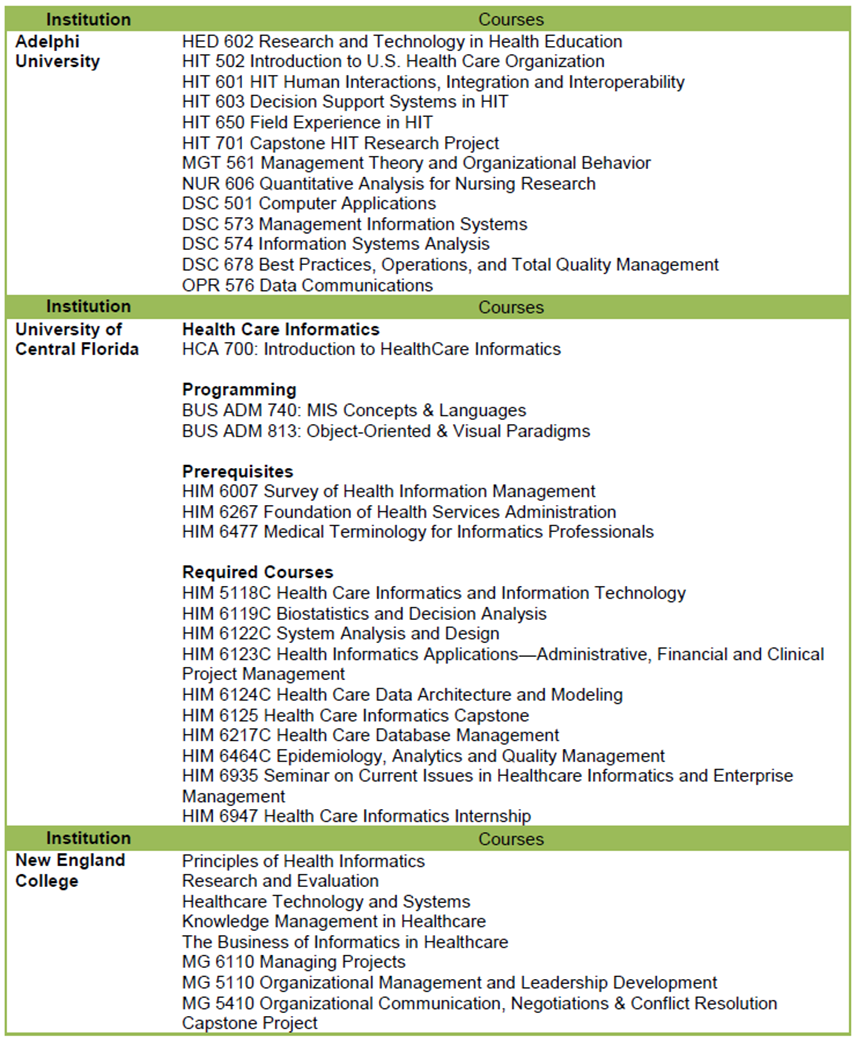

Once the six academic institutions were selected, the website for each Graduate Program for Healthcare Informatics was visited. All of the courses (required and / or electives) were documented and recorded. The courses included in each program are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4: Healthcare Informatics courses at Six Representative Institutions

The web review of graduate programs in Healthcare Informatics shows that the programs are multi-disciplinary in nature. Does a review of the specific courses in each program support that generalization?

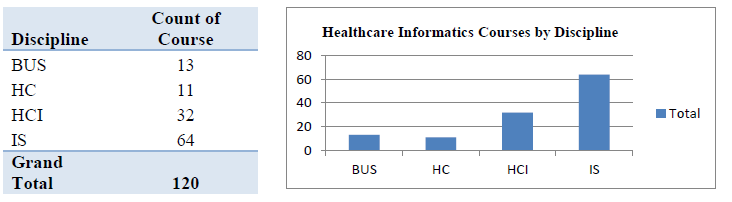

After performing content analysis on the 120 courses from the 6 institutions, the findings do indicate Healthcare Informatics is a multi-disciplinary field. The breakdown is 64% Informations Systems courses, 32% Healthcare Informatics, 10% Business courses and 9% Healthcare courses (see Table 5). This supports the statement that Healthcare Informatics is a multi-disciplinary field.

Table 5: Multi-disciplinary Nature of Courses

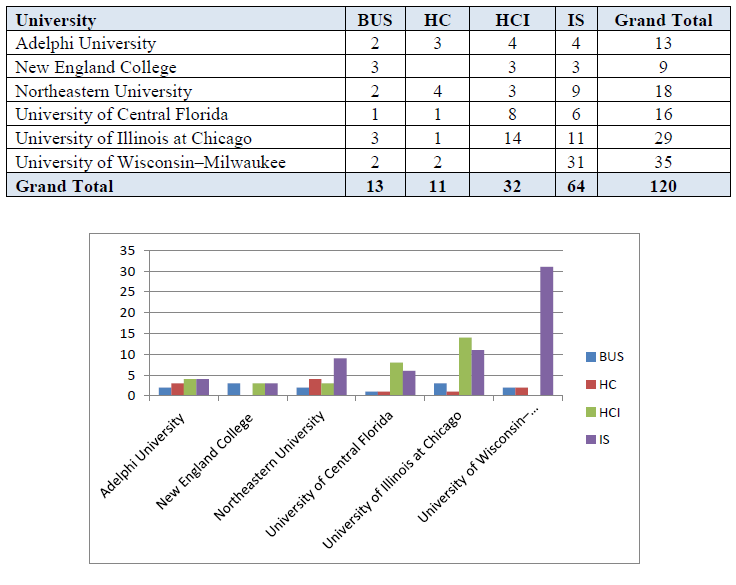

A more detailed review of the data shows two anomalies (see Table 6). The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee had the largest amount of Healthcare Informatics courses, the vast majority being Information Systems related. New England College had the fewest classes – nine (seven of which were 4 credit classes) .

Table 6: Distribution of Courses across Institutions

Conclusions

This pilot study defined the multi-disciplinary nature of Healthcare Informatics and has provided fertile ground for future research. Future research should expand the sample size to include more institutions and also investigate if courses in other disciplines are included in Healthcare Informatics graduate programs. Although not a research question for this pilot study, there appears to be a relationship between the student enrollment in a University and the number of courses offered in the program.

References

AMIA. (2014, 01 08). About AMIA. Retrieved from About AMIA: http://www.amia.org/

Anonymous. (2014, 01 10). College Size: Small, Medium or Large? Retrieved from College 411: http://www.collegedata.com/cs/content/content_choosearticle_tmpl.jhtml?articleId=10006

Arie Hasman, R. H. (2000). Thoughts about Curricula in Health Informatics. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 72:27-33.

Berg, B. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

CAHIIM. (2014, 01 08). Health Informatics Graduate Education Programs. Retrieved from Health Informatics Graduate Education Programs: http://www.cahiim.org/applyaccred_HI_grad.html

Dalrymple, P. (Jun/Jul 2013). Health Informatics: Introduction. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (Online), 18-19.

Eysenbach, G. (2000). Consumer health informatics. British Medical Journal, International edition, 1713-6.

Fowler, F. (2002). Survey research methods. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publisher.

Glebocki, J. (1984). In search of the wild hypothesis : an adventure in statistics for non-statisticians . Parker, CO : Anderson-Bell.

Grove, A. (2014, 01 10). Private University. Retrieved from College Admissions: http://collegeapps.about.com/od/glossaryofkeyterms/g/private-university-definition.htm

HD Covvey, D. Z. (2001). The development of model curricula for health informatics. Medinfo, 10(pt2):1009-13.

Hersh, W. (2007). The full spectrum of biomedical informatics education at Oregon Health & Science University. Methods Inf Med, 46(1):80-3.

Hook, S. A. (2003). Teaching health informatics: designing a course for a new graduate informatics program. J Med Libr Assoc, 91(4): 490–492.

Hovenga, E. (2000). Global health informatics education. Stud Health Technol Inform, 57:3-14.

Reese, S. (May 2012). Trust is a barrier to embracing informatics. Managed Healthcare Executive, 36.

Savel, T. G. (2012). The role of public health informatics in enhancing public health surveillance: CDC’s Vision for Public Health Surveillance in the 21st Century. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 20-24.

Schwirian, P. M. (2013). Informatics and the Future of Nursing: Harnessing the Power of Standardized Nursing Terminology. Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 39(5).

Senate Committe on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. (2014, 10 01). Executive Summary. Retrieved from Executive Summary: http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/for_profit_report/ExecutiveSummary.pdf

State of New Mexico. (2014, 10 10). State of New Mexico Higher Education. Retrieved from Provisions for 5.7.14 NMAC apply to all: http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/nmac/parts/title05/05.007.0014.htm

White, M. (2013). Public Health Informatics: An Invitation to the Field. Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 39(5), 0. Retrieved from http://www.asis.org/Bulletin/Jun-13/JunJul13_White.html#3

White, M. (2013). Public Health Informatics: An Invitation to the Field. Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 0-1.

White, M. (Jun/Jul 2013). Public Health Informatics: An Invitation to the Field. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (Online), 25-29.

AUTHOR BIO

Dr. Thomas Virgono is an Assistant Professor & Director of the Master of Science in Healthcare Informatics at Adelphi University in Greater New York. Prior to joining Adelphi, he was an Associate Professor at Central Connecticut State University [School of Business]. He completed his doctoral studies at Long Island University. He has also been an adjunct professor at Pace University in New York City, a testing invigilator at Monash University in Australia and an Adjunct Professor at Westwood Online.