Towards an Epistemological Understanding of Health Informatics: Academic Backgrounds of the Faculty

by Thomas Virgona, PhD

Assistant Professor

Adelphi University, New York

Abstract

Healthcare Informatics is a relatively new field to academia and is multi-disciplinary by nature. (Virgona, 2014) Although the field of health informatics encompasses several disciplines and subject areas that are familiar and long standing, the field itself is still in a formative state which allows many disciplines to contribute to it through teaching and curriculum development in a way that may not be possible in more established educational programs. (Hook, 2003)

Healthcare Informatics is a relatively new field to academia and is multi-disciplinary by nature. (Virgona, 2014) Although the field of health informatics encompasses several disciplines and subject areas that are familiar and long standing, the field itself is still in a formative state which allows many disciplines to contribute to it through teaching and curriculum development in a way that may not be possible in more established educational programs. (Hook, 2003)

The purpose of this pilot study was to start to define the cross-disciplinary nature of a Healthcare Informatics faculty. Researchers in the field agree that the discipline includes a full spectrum of courses, but the diversity of faculty backgrounds remains vague. In this pilot study, one trend was apparent in the academic backgrounds of the Healthcare Informatics faculty. Computer Science was the most common academic background of the faculty (10 PhD’s, 8 Graduate and 6 Undergraduate Degrees). Interestingly, four faculty members earned a PhD in Health Informatics and no faculty member had earned a graduate/undergraduate degree in Healthcare Informatics. The faculty members of the ten universities investigated in this pilot study indicated 45 unique PhD level disciplines, which, by any means, would be considered inter-disciplinary.

Introduction

Healthcare Informatics is a relatively new field to academia and is multi-disciplinary by nature. (Virgona, 2014) Although the field of health informatics encompasses several disciplines and subject areas that are familiar and long standing, the field itself is still in a formative state that allows many disciplines to contribute to it through teaching and curriculum development in a way that may not be possible in more established educational programs. (Hook, 2003) While academic medical informatics programs are established at a few medical institutions in the United States, increasing numbers of schools are considering this field of study and many traditional departments are seeking and attracting individuals with medical informatics skills.(Greenes & Shortliffe, 1990) There is no common consensus on what defines those skills. The logical extension and question is; what are the academic backgrounds of the faculty teaching in a new inter-disciplinary field?

Literature Review

Despite the increasing mandate for the use of health information technology (HIT) systems in organizations, we do not have comprehensive knowledge of the backgrounds, training, and skills of those who work within the field. There is a lackof information about those who have clinical / technology backgrounds and work in HIT settings. The importance of this workforce, however, is increasingly acknowledged by leaders in HIT. “Dr. David Brailer, Director of the Office of the National Coordinator for Healthcare IT (ONCHIT) stated, “We have a huge manpower crisis coming down the road” in the implementation of HIT systems. Drs. Charles Safran and Don Detmer, of the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA), have called for at least one physician and nurse each at all 6,000 hospitals in the United States to be trained in medical informatics to guide HIT implementation in their local settings (Hersh, 2006, p. 1171).

Medical information systems will continue to evolve with or without staff trained specifically in health care informatics. As discussed above, some of the very talented and innovative people who are now leaders in health care IT come from very different backgrounds, but lack any formal education in medical informatics. One incentive is a financial package that recognizes that health care informatics staff could use their skills in other industries in which pay levels are higher. Most health care organizations cannot compete for staff on the basis of financial compensation (Bell, 1998).

A 2003 study addressed the specific issue of who commonly teaches technology to healthcare professionals. The research found that faculty, who were rated at the “novice” or “advanced beginner” in information technology content and use of information technology tools, often teach information literacy skills. The Southeastern, Central and Pacific regions of the United States projected the greatest need for information technology-prepared nurses. Using Benner’s (1984) novice to expert framework, only two programs rated their nursing faculty as experts in teaching and using information technology. Most nursing programs rated their faculty at the advanced beginner level. Significantly, 18% of programs reported their faculty were novices. Twenty-nine percent of nursing programs reported their faculty members were at the competent level. However, 46% of programs reported either no future plans or no knowledge of any plans to offer information technology education or training in their region (McNeil, Elfrink, Bickford, Pierce, & Beyea, 2003).

The boundaries of healthcare informatics are not well defined. Are individuals who work in information technology departments of medical centers medical informaticians? Are librarians informaticians? There is no common informatics curriculum, nor any common job that anyone with training in the field could define (Hersh, 2002)

Research has found finding the right mix between research/training and service requirements may be challenging. The goal is to attract faculty who understand informatics as a science, not just as a means to reach pragmatic ends (e.g., find a job). Possibly joint appointments for faculty from other units or primary appointments only for informaticians may be a future option (Shortliffe, 2006).

One of the benefits of an education in healthcare informatics is the opportunity to interact with professionals from diverse backgrounds, thereby gaining an appreciation for the varied perspectives, vocabularies and values of each domain. This can be a critical factor in arriving at a solution to a problem. One example of divergent vocabularies emerged in a course in which one of the students commented, “I suddenly recognized the challenges inherent in health informatics when I realized that ‘HIT’ refers to ‘health information technology’, not ‘hemolytic idiopathic thrombocytopenia’” (Dalrymple, 2011, p.43) Programs administered across many academic departments bring diverse perspectives together to determine course content, admissions standards, curriculum and degree requirements.

Since the Internet has removed geographic barriers, this issue is not solely a concern in the United States. In Slovakia, the curriculum content and the quality of education varies among providers and programs. In one research study, the total number of faculty members representing Slovakia was about 40, with different qualifications for academic degrees and professional preparation. The opportunities for further career development and training of students after graduation were not clearly defined. Additionally, the criteria for program self-assessment are not academically sufficient (Rusnakova, Bacharova, Boulton, Hlavacka, & West, 2004).

Research Purpose and Questions

The purpose of this pilot study was to start to define the cross-disciplinary nature of Healthcare Informatics faculty. Researchers in the field agree that the discipline includes a full spectrum of courses, but faculty backgrounds remain diverse.

Consequently, this study addresses two fundamental questions:

- What are the academic backgrounds of Healthcare Informatics faculty?

- Do the represented disciplines mirror the inter-disciplinary nature of the Healthcare Informatics field itself?

Research Methodology

Study Design

For this study, a content analysis of Healthcare Informatics graduate/doctorate degree professor credentials was conducted, using a representative sample of universities. The design goal was to construct a sample framework that corresponded to the population (Universities / Colleges) (Fowler, 2002). A web search was conducted to collect data on the academic backgrounds of healthcare informatics professors.

Content analysis requires two processes: definition of the content characteristics (basic content elements) being examined and application of rules for identifying and recording these characteristics. As well, an objective coding scheme must be applied to the courses (Berg, 2001). For this pilot study, a Web search was conducted to obtain the following data elements:

- Name of Professor

- Teaching At

- Title

- Doctoral Degree Area

- Doctorate Granted at

- Masters Subject

- Masters Granted at

- Bachelors Subject

- Bachelors Granted at

- Notes

One design issue is how well the sample frame corresponds to the population a researcher wants to describe. (Fowler 1993). Searching for healthcare informatics professors web pages potentially has limitations in identifying all relevant academic backgrounds. (Kampov-Polevoi & Hemminger, 2010) Extensive browsing and keyword searching of program web pages was conducted to verify and update faculty details.

An important question that had to be asked was, Is this a true picture? By using a reprehensive sample, the goal was that the information gathered from the sample and the conclusions reflected the same credentials that exist in University settings as a whole (Glebocki, 1984). Specifically excluded from the sample were “for-profit universities”, defined as colleges that are owned and operated by businesses and are ultimately accountable by law for the returns they produce for shareholders. (Senate Committe on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, 2014). The sample selected for this pilot study (January 2014) were universities that have a Graduate and/or Doctoral program who met one of the following criteria:

- Traditional / On the ground

- Public or Private institution

- Large School

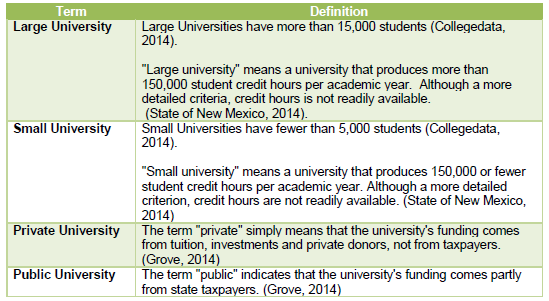

The following working definitions for this study were used (Table 1):

Table 1: Working Definitions

Findings

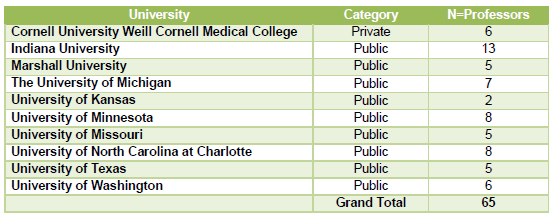

For this pilot study, 65 faculty members from 10 universities were analyzed. The ten universities selected and the number of faculty included in this pilot study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Pilot Study Data Collection

In this pilot study, two fundamental questions were investigated:

- What are the academic backgrounds of Healthcare Informatics faculty?

- Do the represented disciplines mirror the inter-disciplinary nature of the Healthcare Informatics field itself?

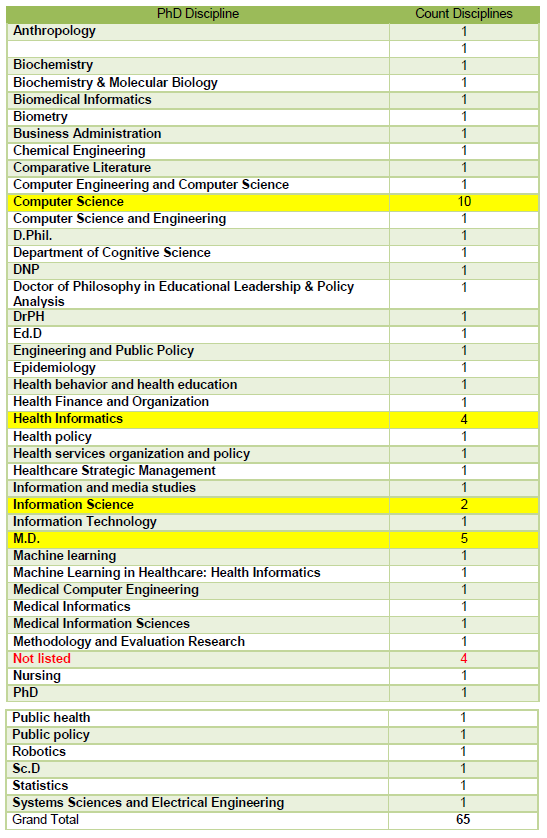

The academic backgrounds of the faculty in this pilot study were fairly diverse. Faculty PhDs in this sample were granted in the following areas (see Table 3):

Table 3: Sample PhD by Discipline

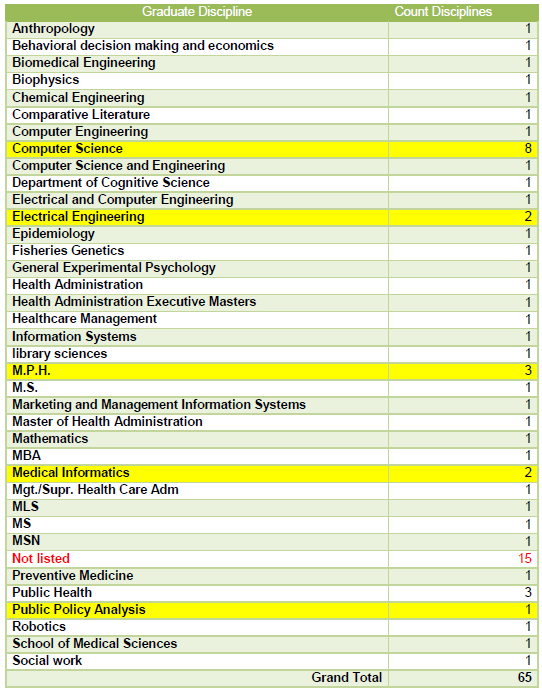

The Graduate/Master’s Degrees represented in this sample are summarized in Table 4:

Table 4: Sample Graduate Degree by Discipline

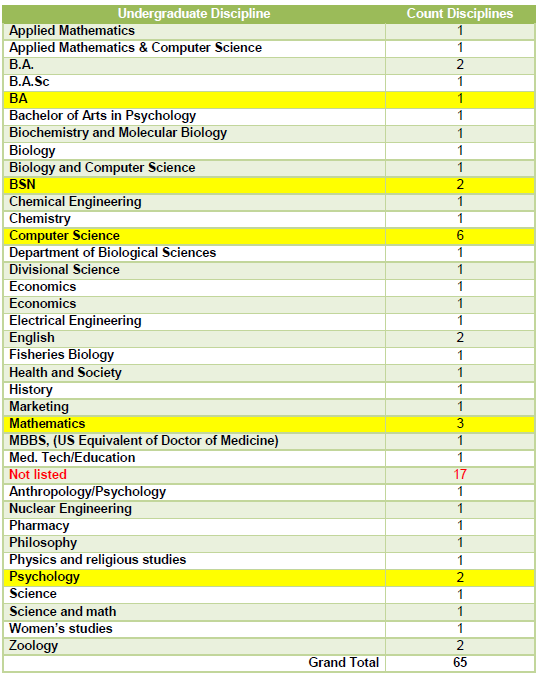

Undergraduate Degrees represented in the sample population are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5: Sample Undergraduate Degree by Discipline

In this pilot study, one trend was apparent in the academic backgrounds of the Healthcare Informatics faculty. Computer Science was the most common academic background of the faculty (10 PhDs, 8 Graduate and 6 Undergraduate Degrees). Interestingly, four faculty members earned a PhD in Health Informatics yet none of the faculty members earned a graduate or undergraduate degree in the discipline.

These findings raised the question, “Do the disciplines mirror the inter-disciplinary nature if the Healthcare Informatics field itself?” The 65 faculty members from the ten universities investigated in this pilot study represented 45 unique PhD disciplines. By any measure, the results are distinctly inter-disciplinary. Thirty-nine graduate disciplines and thirty-seven undergraduate areas were represented in the academic backgrounds of the Healthcare informatics faculty in the sample.

Discussion

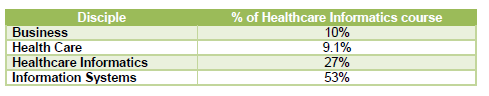

The results of this pilot study showed diverse academic backgrounds were represented in the 10 sample universities and the 65 professors selected. These results provided support for the inter-disciplinary nature of Healthcare Informatics. Previously, Virgona (2014) found the course distribution of Healthcare Informatics to follow this inter-disciplinary path (see Table 6):

Table 6: Healthcare Informatics course distribution

While 53% of the courses in Healthcare Informatics are in the Information Systems discipline, less than 2% of the PhDs represented in this pilot study were in Information Systems. In a similar discovery, 10% of Healthcare Informatics curriculum is business related yet there is no evidence of any business background in the sample Healthcare Informatics faculty. Despite this disparity, it is not clear or known if this is an issue that needs to be addressed.

References

Bell, M. J. (Aug 1998). The IT staffing crisis. Health Management Technology , 19(9), 65-66.

Berg, B. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Collegedata. (2014, 01 10). College Size: Small, Medium or Large? Retrieved from College 411: http://www.collegedata.com/cs/content/content_choosearticle_tmpl.jhtml?articleId=10006

Dalrymple, P. W. (Jun/Jul 2011). Data, Information, Knowledge: The Emerging Field of Health Informatics. Bulletin of the American Society for INformatin Science and Technology, 37(5), 41-44.

Fowler, F. (2002). Survey research methods. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publisher.

Glebocki, J. (1984). In search of the wild hypothesis : an adventure in statistics for non-statisticians . Parker, CO : Anderson-Bell.

Greenes, R. A., & Shortliffe, E. H. (1990). Medical InformaticsAn Emerging Academic Discipline and Institutional Priority. JAMA , 263(8), 1114-1120.

Grove, A. (2014, 01 10). Private University. Retrieved from College Admissions: http://collegeapps.about.com/od/glossaryofkeyterms/g/private-university-definition.htm

Hersh, W. (2002). Medical informatics education; an alternative pathway for training informationists. J Med Libr Assoc , 90 (1), 76-79.

Hersh, W. (2006). Who are the Informaticians? what we know and should know. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 13 (2), 166-170.

Hook, S. A. (Oct 2003). Teaching health informatics: designing a course for a new graduate informatics program. Journal of the Medical Library Association , 91(4), 490-2.

Kampov-Polevoi, J., & Hemminger, B. M. (2010). Survey of Biomedical and Health Care Informatics programs in the United States. Journal of the Medical Library Association , 98 (2), 178–181.

McNeil, B. J., Elfrink, V. L., Bickford, C. J., Pierce, S. T., & Beyea, S. C. (August 2003). Nursing information technology knowledge, skills, and preparation of student nurses, nursing faculty, and clinicians: A U.S. survey. Journal of Nursing Education , 42(8), 341-9.

Pearson, A., & Urquhart, C. (2002). Health informatics education–working across the professional boundaries. Library Review , 51 (3/4), 200-210.

Rusnakova, V., Bacharova, L., Boulton, G., Hlavacka, S., & West, D. J. (2004). Assessment of Management Education and Training for Healthcare Providers in the Slovak Republic. Hospital Topics , 32(3), 18-25.

Senate Committe on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. (2014, 10 01). Executive Summary. Retrieved from Executive Summary: http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/for_profit_report/ExecutiveSummary.pdf

Shortliffe, E. (2006, 01 19). An Overview of Biomedical Informatics. Retrieved from An Overview of Biomedical Informatics: http://www.apami.org/apami2006/ppt/1027-Shortliffe.pdf

State of New Mexico. (2014, 10 10). State of New Mexico Higher Education. Retrieved from Provisions for 5.7.14 NMAC apply to all: http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/nmac/parts/title05/05.007.0014.htm

Virgona, T. (2014). Towards an Empirical Definition of Graduate School Healthcare Informatics. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics , 9 (1 and 2), p=3555.

AUTHOR BIO

Dr. Thomas Virgono is an Assistant Professor & Director of the Master of Science in Healthcare Informatics at Adelphi University in Greater New York. Prior to joining Adelphi, he was an Associate Professor at Central Connecticut State University [School of Business]. He completed his doctoral studies at Long Island University. He has also been an adjunct professor at Pace University in New York City, a testing invigilator at Monash University in Australia and an Adjunct Professor at Westwood Online.