Examining the Nature of Palliative Care Consult Team (PCCT) Referrals seen by Clinical Nurse Specialists

By Kalli Stilos, RN MSN CHPCN

Clinical Nurse Specialist, Palliative Care Consult Team

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario

Tammy Lilien, BA

Special Projects Coordinator, Palliative Care Consult Team

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario

Dr. Lesia Wynnychuk, MD

Family Physician, Palliative Care Consult Team

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario

Patricia Daines, RN MSN CHPCN

Advanced Practice Nurse, Palliative Care Consult Team

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario

Abstract

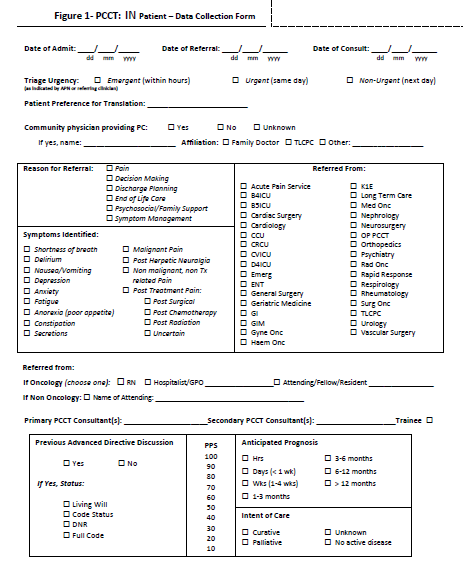

The purpose of this article is to describe the demographic and clinical features of patients referred to the Palliative Care Consult Team and seen initially by a Clinical Nurse Specialist over a five year period from 2008 to 2012. The Clinical Nurse Specialists on the in-patient Palliative Care Consult Team work within an inter-professional consultative model. In acute care settings, Clinical Nurse Specialists are routinely encouraged to collect data to support their contributions to clinical practice.

The purpose of this article is to describe the demographic and clinical features of patients referred to the Palliative Care Consult Team and seen initially by a Clinical Nurse Specialist over a five year period from 2008 to 2012. The Clinical Nurse Specialists on the in-patient Palliative Care Consult Team work within an inter-professional consultative model. In acute care settings, Clinical Nurse Specialists are routinely encouraged to collect data to support their contributions to clinical practice.

An existing database created and maintained by the Palliative Care Consult Team containing patient demographics and consult-specific information was used to examine retrospective data on Clinical Nurse Specialists’ clinical practice. The majority of patients followed by a Clinical Nurse Specialist were referred for pain and symptom management or end-of-life care. Only a small portion of patients referred for discharge planning and psychosocial support were seen by the clinical nurse specialist. An understanding of current clinical practices of Clinical Nurse Specialists on the Palliative Care Consult Team is needed for growth of the role, and for innovation around future care delivery models in the acute care setting.

Key words: clinical nurse specialist, role, database, palliative care consult team, retrospective data

Background

Palliative Care at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC) is comprised of the Palliative Care Consult Team (PCCT), and the Palliative Care Unit (PCU). Patients from the acute care setting may be transferred to the PCU when their prognosis is less than 3 months. The PCU functions distinctly from the consult team, with its own respective staff.

The inpatient PCCT consists of two Clinical Nurse Specialists and five Palliative Medicine Physicians, with residents, fellows and other learners rotating through the Palliative Care Service at a large urban tertiary care centre.

According to the Canadian Nurses Association, a Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) is a registered nurse who holds a master’s or doctoral degree in nursing, and has expertise in a clinical nursing specialty (CNA, 2008). The palliative care CNS provides care to patients with complex palliative care needs and their families. The CNS contributes to high-quality patient care through five components that make up this advanced practice nursing role: advanced practitioner, educator, researcher, and administrator/leader (Donald, 2008). Within a collaborative practice, a CNS has ample opportunity to use their knowledge, competencies and skills to enhance the quality of the clinical care they provide (CNA, 2008).

The CNS role has been part of the PCCT at SHSC since the team’s inception in 1999, under the Oncology Program. The CNS’ full-time equivalent (FTE) from 2002-2011 was 1.6; in 2012 this was reduced to 1.2 FTE due to financial constraints. In their current role on the PCCT, CNS act as consultants, collaborating with palliative care physicians and other members of inter-professional primary teams to provide care to patients and their families. Once a referral for palliative care has been received it is randomly delegated to the next available clinician (physician; CNS; or resident). Upon receiving a referral, the CNS completes an initial consult (which includes: patient history, assessment, review of symptom concerns) and develops a management plan that is subsequently reviewed with a palliative care physician.

Clinical Nurse Specialists on the PCCT see patients referred from medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgical oncology, gynecology oncology, general internal medicine, nephrology, neurology, trauma, geriatrics, cardiology, urology, otolaryngology and critical care. Reasons for consultation include: pain, symptoms (such as: anorexia, anxiety, constipation, delirium, depression, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, secretions, shortness of breath), psychosocial/family support, decision-making support, discharge planning, and end-of-life care for imminently dying patients.

In acute care settings, CNS are routinely encouraged to collect data to support their contributions to clinical practice (Charter, 2003, De Vito Dabbs, Curran, Lenz, 2000). The Centre to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) encourages palliative care programs to explore key program components such as operational, clinical, customer, and financial metrics to ensure program quality and sustainability. “Tracking operational data about patients seen by the consultation service (e.g. diagnosis, referring service, disposition etc) is necessary for … planning for program staffing to accommodate growth in demand for services, and for both program directors and hospital administrations to gauge overall program impact on care quality and use of health care services” (Weissman et al. 2008).

Graves et al (1995) highlighted the notion that advance practice nurses should have a good grasp of the nursing data in their own specialty. Furthermore, Grave and Corcoran (1988) emphasized that databases allow data to be retained in a form that can be used for knowledge building about patient populations. The PCCT database has the capacity to provide consult-specific information on patients seen initially by a CNS.

Purpose

The purpose of this retrospective study is to describe the demographic and consult-specific information of patients referred to the PCCT and seen initially by a CNS over a five year period, from 2008-2012. The identification of evolving data trends across referred patients allows for a more thorough understanding of the CNS role contributions on the PCCT.

Methods

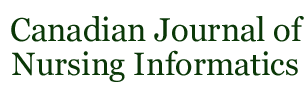

After approval by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC) Research Ethics Board (REB), a retrospective PCCT inpatient data collection form review was completed using data from all patients seen by the PCCT between Jan 1st, 2008 and Dec 31st, 2012. Patient demographics and consult-specific information had been collected prospectively in a secure database since 2008. The existing database is maintained on a Sunnybrook desktop, saved to the server and is accessible only by a password unique to each PCCT member. Although the database contains a wealth of invaluable demographic and consult-specific information, it lacks the capacity to paint a full clinical picture of each patient’s complex needs and associated care plans. All data are collected on a comprehensive standardized inpatient data collection form (see Figure 1) and then entered into the database by the administrative team. Demographic data collected includes: age, gender and diagnosis. Consult-specific information included: reason for referral, referring service, malignant versus non-malignant disease, time from initial consult to death (when death information was available), and patient disposition (discharged from hospital, transferred to PCU, etc).

CLICK FOR FULL VIEW

Results

Data collated from the database provides an overview of the demographic and consult-specific information of patients seen by the CNS.

Characteristics of the Sample

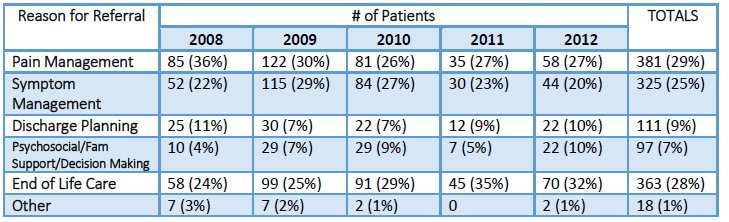

Inpatient database forms from 850 patients were reviewed. In many instances, a new patient referred to the service may have more than one reason for referral (for example, decision making and discharge planning). As such, there are 850 patients in the sample but over 1200 reasons for referral were identified. The distribution of reasons for referral was: pain management (29%), end-of-life care (28%), symptom management (25%), discharge-planning (9%), psychosocial/family support/decision making (7%) and other issues (1%).

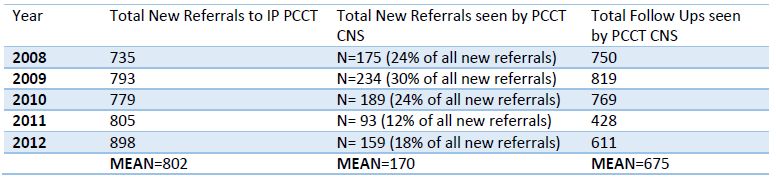

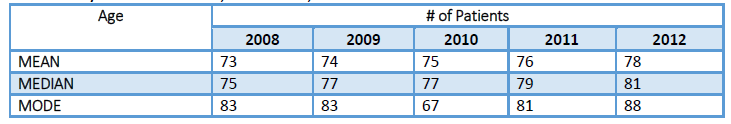

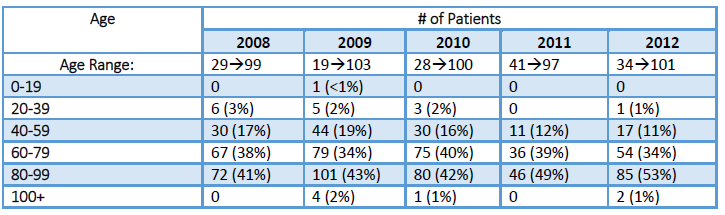

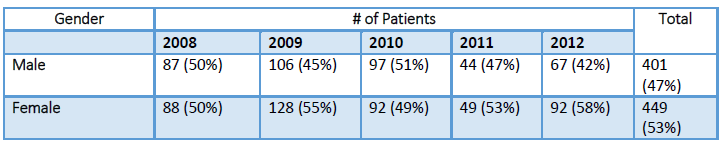

Patient demographics and consult specific information are illustrated in Tables 1 through 9 below. The median age of patients at the time of consult was 78 years old (age range 20 to 103) and gender distribution was 53% female and 47% male. Consultations were distributed amongst three main referring services; General Medicine (38%), Medical Oncology (25%), and Radiation Oncology (11%).

Diagnoses were differentiated by the presence of malignant or non-malignant disease. The majority of patients seen had an underlying malignancy (61%), and the three most common sites of malignancy were gastrointestinal, lung or gynecological. Non-malignant diseases were reported in 39% of the patients, with stroke, pneumonia, Congestive heart failure (CHF) and dementia being the most prevalent diagnoses.

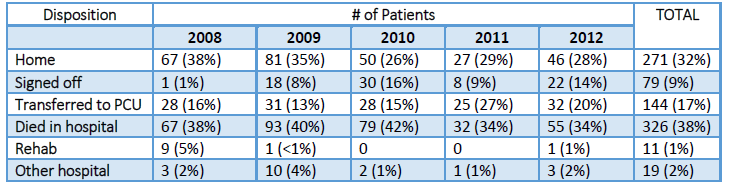

Summary patient dispositions indicated that 38% of patients died on the acute care ward, 32% were discharged home, 17% were transferred to a Palliative Care Unit, 9% were signed off from the PCCT service, 2% were transferred to another hospital and 1% of patients were transferred to a rehabilitation facility. Within the study sample, 69% of patients had death information available in the PCCT database. Among these patients, after the initial consult, 46% died within one month and of these, 29% died within 72 hours.

Discussion

Prevalent Symptoms

Hospitalized patients who require palliative care expertise have a range of care needs. The literature indicates that the most prevalent of these needs is the relief of pain and other symptoms, which may include shortness of breath, fatigue, and anxiety/depression (Casarett et al. 2011, Tapsfield & Bates, 2011) and less obvious are needs such as advance care planning and decision making around treatment (Milligan, 2012).

It is not surprising that pain management is a predominant component of consults seen by the CNS; as pain is a common symptom in most illnesses that are life-threatening and progressive in nature (Oneschuk, Hagen, Macdonald, 2012). A survey of 73 Oncology Advanced Practice Nurses (APNs) found that pain and symptom management were the primary focus of their clinical work (Bryant-Lukosius, 2007). Symptom Management referrals to the PCCT can include support for symptoms like: anorexia, anxiety, constipation, delirium, depression, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, secretions and shortness of breath. Since, malignant and non-malignant diseases are becoming increasingly complex; there is a greater need to offer symptom control measures to those who have recurrent and progressive illnesses (Oneschuk, Hagen, Macdonald, 2012).

The collated data from the PCCT Data Collection form highlighted the main reasons for referral. Clinical Nurse Specialists were most likely to be involved in the care of patients who were referred for pain (29%), end-of-life care (28%) and symptom management (25%). Amongst patients referred for symptom management, the most frequently experienced symptoms included shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting, and delirium (see Table 10 below). Less clinical time was spent supporting patients who required discharge planning (9%) and psychosocial/family support/decision making (7%).

End-of-Life Care

Requests for end-of-life (EOL) care comprised 28% of referrals seen by a CNS. EOL care is focused on symptoms such as pain, shortness of breath, agitation, and secretions in patients who are imminently dying, as well as support and education for families. Symptom management interventions can dramatically improve quality of life during a patient’s last days or hours (Walling, 2008). Froggatt et al. (2002) studied a palliative care CNS who provided EOL care to elderly residents in nursing and residential care homes by helping to alleviate both physical and existential symptoms. By spending a considerable amount of time with the patient and family, the CNS in this study was able to ensure that their needs were met.

Other Reasons for Referral

A small portion of the CNS practice involved work associated with discharge planning (9%) and psychosocial/family support/decision making (7%). Bryant-Lukosius (2007) found that APNs spent “less time providing care related to patient and family education, counseling or health promotion” (p. 58). The low percentages in this study are not particularly surprising given that SHSC employs social workers and discharge coordinators who are primarily responsible for facilitating discharge plans for patients. Moreover, a psychosocial oncology team based primarily in the ambulatory setting is available as an additional resource for psychosocial support and counseling. The existence of these services may help to explain the low number of patients referred to the PCCT for the aforementioned reasons.

Elderly

The demographic data presented in this study indicated that CNS are working with an older population, with a median patient age of 78 and a mode age of 83. This advanced age is not surprising given that the Canadian population is aging and seniors comprise the largest growing age group. In 2011, an estimated 5.0 million Canadians were 65 years of age or older, (Employment & Social Development Canada). This growth will only continue to increase in the years to come mainly due to increased life expectancy and the aging of the baby-boomer generation. It is estimated that in the next 25 years, the number of Canadians aged 65 and older will approach 10.4 million (Employment & Social Development Canada). “In fact, by 2041, one in four Canadians is expected to be 65 or over” (Human Resources & Skills Development Canada, 2011). With a rapidly growing aging population and an enhanced role for palliative care clinicians in the management of non-malignant illnesses, demand for palliative care services is likely to increase dramatically. Since more than half of deaths occur in acute care hospital settings (Statistics Canada, 2010), CNS in palliative care are ideally positioned to assist elderly patients with advanced illnesses and their families as they experience the final phase of their life (Mahler, 2010).

Implications for Practice

The literature clearly indicates that CNS are challenged to describe their distinctive contributions to patient care and patient outcomes (De Vito Dabbs, Curran, Lenz, 2000; Weissmanet al. 2008).). The CNS role may be disadvantaged by its multifaceted nature, variations in scope of practice, and inconsistencies in how health care institutions choose to utilize the role. The lack of quantifiable data on the impact of the CNS role on cost-effectiveness, quality of care and patient outcomes is of particular concern (McGonigle, 1996). Exploring the PCCT database constitutes a first step in reviewing the role of the CNS as it provides opportunities to view a snapshot of CNS practice and identify clinical trends.

Due to the organizational structure of SHSC, the PCCT CNS are strongly aligned with oncology colleagues. However, given that half of their clinical practice is spent caring for non-oncology patients, CNS’ would likely benefit from formalizing a partnership with other APN colleagues within the same institution (Pantilat, O’Riordan & Bruno, 2014). Benefits of a partnership may include: improved patient care, enhanced pain and symptom management and greater consistency in end-of-life care. Additionally, these partnerships could provide: a foundation for the creation of educational programs for front line staff, the development of shared care models for advance care planning, and opportunities for interprofessional research.

The CNS on the PCCT work predominantly with an elderly population. As this population grows, the volume of elderly patients who require care, especially palliative care, is likely to increase. If the number of CNS providing care does not increase to align with the growing elderly population, a service gap will be created between the patients who require palliative care and the clinicians who provide that care. Hospital leadership should take these findings into account for the purpose of strategic planning.

Analysis of the data enabled the CNS to determine that their practice involved the care of patients with particular malignant and non-malignant diseases. For patients with a malignant diagnosis, CNS were most likely to follow gastrointestinal, lung and gynecological cancer patients. The 2007 study by Bryant-Lukosius, Green, Fitch et al. reported similar findings whereby gastrointestinal, lung and gynecological cancers were among the top six areas of clinical practice for oncology APNs. For patients with non-malignant disease, a CNS was most likely to provide care for patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke, and dementia.

Over the five year study period, 38% of the patients who received PCCT consultations by the CNS died on an acute care ward. Death data was only available for 69% (588) of patients. It was noted that 29% of those patients died within 72 hours of consultation and 46% died within 30 days. The death data clearly defines a patient population that is elderly, has serious, complex and potentially-life threatening or life-limiting conditions and may die in hospital.

Limitations

The database currently being utilized by the PCCT was developed specifically for this program and was designed to capture the clinical workload of the PCCT. It may, therefore, not be generalizable to other clinical practices within and outside the organization. Notably, this data could be used by other CNS in palliative care programs who are interested in comparing their data.

While the number of patients seen by the PCCT is accurately captured by the database, the complex nature of patients’ needs and care plans is not reflected; nor are additional CNS encounters with patient and their families and the total time spent with them. The provision of palliative care encompasses a wide range of intangible, immeasurable and qualitative components that cannot be captured in a database.

Conclusion

This study served as a five year retrospective review of the patient population seen initially by a CNS on the Palliative Care Consult Team at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. Examining this data constitutes a preliminary look at CNS practice and provides a solid platform on which to build future role development. It is the responsibility of all individuals in the CNS role to collect, review, summarize and disseminate role-specific data. Future research seeking a deeper understanding of how a palliative care CNS works with patients and families could shape future development of the role, and help fulfill the mandate to provide the highest quality of care to patients and their families.

References

Bryant-Lukosius D, Green E, Fitch M, Macartney G, Robb-Blenderman L. & McFarlane S, et al. (2007). A survey of oncology advanced practice nurses in Ontario: profile and predictors of job satisfaction. Nursing Leadership, 20(2): 50-68.

Casarett D, Smith J.M. & Richardson D. (2011). The optimal deliver of palliative care: a national comparison of the outcomes of consultation teams vs inpatients units. Archives of Internal Medicine. 171(7): 649-655.

Charter K. (2003). Advance Practice in Acute and Critical Care. AACN Clinical Issue, 14(3): 282-294.

Canadian Nurses Association (CNA). (2008). Advanced Nursing Practice: A National Framework. Retrieved February 13, 2013 from http://www2.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/ANP_National Framework_e.pdf

DeVito Dabbs A, Curran C.R. & Lenz E.R. (2000). A database to describe the practice component of the CNS role. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 14(4): 174-83.

Donald, F.D, Bryant-Lukosius, D, Martin-Misener S, Kaasalainen, K. & Kilpatrick, N.et al. (2010). Clinical Nurse Specialists and Nurse Practitioners: Title Confusion and lack of role clarity. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership, 23 (Special Issue): 189-210.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (n.d.) Indicators of well being in Canada Canadians in context-Aging population Retrieved December 18, 2015 from http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=33

Froggatt, A.K, Poole. K. & Hoult, L. (2002). The provision of palliative care in nursing homes and residential care homes: a survey of clinical nurse specialist work. Palliative Medicine, 16(8): 481-487.

Graves, J.R., Amos, L.A. & Huether, S, et al. (1995). Description of a graduate program in clinical nursing informatics. Computers in Nursing, 13, 60-69.

Graves, J.R, & Corcoran, S. (1988). Design of nursing information systems: conceptual and practice elements. Journal of Professional Nursing, 4(3) 168-177.

Human Resources & Skills Development Canada.(n.d.) Canadians in Context-Aging Population. Retrieved April 9, 2013 from http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=33

Mahler A. (2010). The clinical nurse specialist role in developing a gero-palliative model of care. Clinical Nurse Specialist; 24(1):18-23.

Martin DR, O’Brien JL, Heyworth JA, Meyer NR. The collaborative healthcare team: tensive issues warranting ongoing consideration. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005; 17(8): 325-330.

McGonigle, D. (1996). Nursing Informatics: Quantifying the CNS Role. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 10(6): 300.

Rapp M.P. (2003). Opportunities for advance practice nurses in the nursing facility. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 4(6): 337-43.

Oneschuk, D., Hagen, N. & MacDonald N. (2012). Palliative Medicine A case-based manual (3rd Edition). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Pantilat, S.Z., O’riordan, D.L & Bruno, K.A. (2014). Two steps forward, one step back: Changes in palliative care consultation services in California hospitals from 2007 to 2011. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(11); 1214-1220.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Table 102-0509-Deaths in hospital and elsewhere, Canada, provinces and territories, annual, CANSIM (database). Retrieved January 3, 2013 from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/pick-choisir?lang=eng&p2=33&id=1020509

Tapsfield, J. & Bates M.J. (2011). Hospital based palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa: a six month review from Malawi. BMC Palliative Care. 10(12). Retrieved January 6, 2016 from http://bmcpalliatcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-684X-10-12

Tringali, C.A., Murphy, T.H. & Osevala, M.C. (2008). CNS practice in a care coordination model. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 22(5), 231-239.

Walling, A., Brown-Saltzman, K., Barry, T., Quan, R.J. & Wenger, N.S. (2008). Assessment of implementation of an order protocol for end-of-life symptom management. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 11(6): 857-865.

Weisserman, D.E., Meier, D.E. & Spragens, L.H. (2008). Centre to advance palliative care palliative care consultation service metrics: consensus recommendations. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 11(10), 1294-1298.

Biographies

Kalli Stilos

Kalli Stilos is an Advance Practice Nurse for the Palliative Care Consult Team. Her role with the team began in 2003. She’s completed her Master of Science in Nursing at D’Youville College in Buffalo, New York along with her Canadian Nurses Association Specialty Certification in Palliative Care (CHPCN). Over the years Kalli Stilos and Patricia Daines have published numerous articles and have an interest in highlighting their nursing role and contribution to the palliative care field. She currently holds an Adjunct Lecturer position at the University of Toronto’s Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing. Currently, she is also involved in the institution-wide Quality Dying Initiative at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre where she serves as Professional Development Lead for of the Steering Committee. On a daily basis she’s involved in clinical practice working with front line staff, along with patients and their families managing various palliative care issues.

Tammy Lilien

Tammy Lilien completed her BA from McGill University, majoring in Psychology and Sociology. As Special Projects Coordinator for the Palliative Care Team, she has collaborated interprofessionally on the Ontario Cancer Symptom Management Collaborative and various Quality Improvement and research projects. In 2009, Tammy received the Bertin Award for Excellence in Customer Service.

Dr. Lesia Wynnychuk

Dr. Wynnychuk is a Family Physician practicing within the inter-professional Palliative Care Consult Team at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and the Odette Cancer Centre in Toronto. She holds the rank of Assistant Professor, part-time, in the Division of Palliative Care within the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto. Currently, she is involved in the institution-wide Quality Dying Initiative at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre where she serves as an Executive Member of the Steering Committee and the Lead of its Literature Review Working Group.

Patricia Daines

Patricia Daines is an Advance Practice Nurse on the Palliative Care Consult Team. She completed her Masters in Nursing from the University of Toronto and has a Canadian Nurses Association Specialty Certification in Palliative Care (CHPCN). She’s been with the team since its inception in 2001 and was Acting Co-Director from 2005-2006. She currently holds an Adjunct Lecturer position at the University of Toronto’s Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing. Currently, she is involved in the institution-wide Quality Dying Initiative at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. On a daily basis she’s involved in clinical practice working with front line staff, along with patients and their families managing various palliative care issues.

Palliative team graphic by Icons8 from Flaticon is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Made with Logo Maker