A Review of Informatics Competencies Tools for Nurses and Nurse Managers

*Rawda Abdulla Ali, RN MN,

Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

Email: Rali1@hamad.qa,

Rama880@gmail.com

Kathleen Benjamin, RN, PhD;

University of Calgary in Qatar

Sadia Munir, PhD,

University of Calgary in Qatar

Noha Saleh Othman Saleh Ahmed RN, MN,

Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

* Corresponding Author

Abstract

In light of the rapid innovation in healthcare, there is the need to measure and enhance nurses and nurse managers’ informatics skills and knowledge. The objectives of this MN project were: (1) to search and identify existing informatics competency tools, (2) to assess these tools using predetermined criteria; for example, psychometrics and practicality of the tools, and (3) to recommend informatics competency tools that can be applied within the context of Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) in Qatar. Eight tools were identified and assessed using predetermined criteria. Based on the results of the assessment, two tools were recommended. The recommended tool for nurses was the one described by Chang, Poynton, Gassert & Staggers (2011) and the recommended tool for nurse managers was the tool described by Hart (2010).

Key recommendations for HMC include the development of a committee to review the feasibility of applying the two tools, followed by pilot testing and further psychometric testing. Additionally, it is important to conduct a larger study at HMC to measure nurses’ and nurse managers’ informatics competencies. The results can then be used to help develop tailored informatics training programs at HMC.

Introduction

The term nursing informatics was defined first by Ball and Hannah in 1984, then redefined by Graves and Corcoran in 1989 (Murphy, 2010). Graves and Corcoran (1989) defined nursing informatics as “a combination of nursing science, information science, and computer science to manage and process nursing data, information and knowledge to facilitate the delivery of health care” (Graves & Corcoran, 1989, p. 227). The aspects of this definition demonstrate the use of information and technology to enhance nursing practice. Stragger, Gassert & Curran (2001) defined nursing informatics competencies (NIC) as “the integration of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in the performance of various nursing informatics activities within prescribed levels of nursing practice” (p. 306).

Assessment of competencies refers to the appraisal of the state of an individual’s capability of being qualified and competent to complete specific tasks. To be competent implies that an individual has the knowledge, attitude, and skills to respond to the demands of work (Chung & Staggers, 2014).

Nursing informatics competencies has become essential for nursing practice globally (Lin, Hsu, & Yang, 2014; Schleyer, Burch, & Schoessler, 2011). Due to rapid innovation in healthcare, there is the need to measure and enhance nurses’ informatics skills and knowledge. Measuring and enhancing informatics competencies may help nurse managers to advance nurses’ contributions to healthcare technological innovations (Schleyer et al, 2011).

The History of Technology in Healthcare

The use of technology in healthcare sectors is not new, especially within nursing practice. In the 1960s, computer systems were introduced in hospitals for financial and billing purposes. In the 1970s, nurses were significantly involved in designing and applying information technology in hospitals. In the 1980s, nurses used technology and information systems to assist with patient care; for example, admissions, food, and medication administration (Murphy, 2010). Now, healthcare technologies have intensively transformed and changed the healthcare sector with extensive high-tech devices and information applications in all areas that have become part of a nurses’ daily work routines (Crist-Gundman & Mulrooney, 2011).

Benefits of Technology

Some of the benefits of using information technologies in the healthcare sector include automation of clinical data records, accessing patient information any time, enhancing real time clinical communication, reducing documentation and clinical error, minimizing paper use, making data collection and analysis easier, tracking the patient care process, supporting decision-making processes, and enhancing hospital operation and management (Eley, Soar, Buikstra, Fallon, & Hegney, 2009; Crist-Grundman & Mulrooney, 2011; Mays, Kelley, & Sanford, 2008; Piscotty & Tzeng, 2011; Sweis et al., 2014 & Turner, Kitchenham, Brereton, Charters & Budgen, 2010).

Results of a literature review that studied the benefits of using information technology in healthcare showed that 92% of the literature prior to 2011 demonstrated positive benefits of using information technology (Buntin, Burke, Hoaglin, & Blumenthal (2011). The major themes related to using technologies within healthcare focus on improving quality of care and patient safety (Bowcutt et al., 2008; Buntin, Burke, Hoaglin, Blumenthal, 2011; Lucero, Haomiao, De Cordova, & Stone, 2011; Piscotty, Kalisch, & Gracey-Thomas, 2015).

Quality of Care and Technology

Several studies have focused on the relationship and impact of information technology on quality of nursing care (Ammenwertha, Rauchegger, Ehlers, Hirschc, & Schaubmayr, 2011; Bowcutt et al., 2008; Lucero et al., 2011; Piscotty et al., 2015). Ammenwertha et al. (2011) assessed the impact of using a nursing information system on the quality of nursing care. This mixed method study assessed the nursing documentation system before and one year after implementation. The results indicated that the quality of nursing care improved after implementing a nursing information system as it enhanced nursing documentation, patient care plans, and nursing workflow.

Bowcutt et al. (2008) conducted a survey to assess nurses’ perceptions in implementing and using an intravenous medication infusion system to enhance nursing care and the reporting of medication errors. The results showed that an intravenous medication infusion system helped nurses to administer medication safely. In addition, nurses perceived that this technology helped to enhance their job satisfaction due to decreased anxiety about making a medication error.

Lucero et al. (2011) studued the effectiveness of using an electronic data tracking system to measure quality of care by examining the variation and relationship between nurses’ response time, patients’ needs, and nurse staffing. The data retrieved from the nursing tracking system were patient census, patients’ needs, and nurses’ response time. The patients’ movement database system was used to retrieve data related to patients’ admission, transfer, and discharge data. The results highlighted that there was no significant relationship between nurses’ response time and staffing. Although nurses’ response time increased with patients’ admission, their response time was not affected by discharge and transfers. In this study, the authors recommended that demands on staffing should be based on patient turnovers, as well as increased patient needs. These authors demonstrated the important role that technology plays in helping nurses to provide appropriate tailored patient care and nurse managers to make appropriate decisions.

Piscotty et al. (2015) studied nurses’ perceptions related to the impact of information technology and an electronic reminder system in enhancing their practice. The results supported the positive beneficial impact of using information technology in nursing care. The electronic reminder helped to reduced missed nursing care issues. In summary, these studies demonstrate the positive relationship between healthcare technology and quality of patient care.

Patients’ Safety and Technology

Some studies examined the effect of healthcare technology on patient safety (Mason, Roberts-Turner, Amendola, Sill, & Hinds, 2014; Wulff, Cummings, Marck, & Yurtseven, 2011). Mason et al. (2014) conducted a survey to identify nurses’ perceptions related to the effect of smart pump technology on patient safety and error reduction. The results indicated that nurses had positive perceptions about the use of the smart pump technology because it helped them to provide safe patient care. Wulff et al. (2011) conducted a systematic review to identify the relationship between medication technology and the reduction of medication errors in order to enhance patient safety. The results demonstrated a positive and significant relationship between the use of medication administration technology and medication error reduction.

Barriers to the use of technology

The introduction of technology has not been without tensions. The findings of a study that examined Australian nurses’ perceptions of the barriers to technology use showed that age affected nurses’ attitudes towards accepting technology in nursing (Eley et al., 2009). That is, older age was associated with less positive attitudes towards accepting technology. The results also showed that job level impacted level of acceptance. Senior level nurses showed greater acceptance of information technology compared to junior level nurses. The most significant barriers were: a lack of interest and training in technology and a belief that using technology took nurses away from patient care. The authors highlighted the importance of identifying these barriers in order to address nurses` e-training and education needs related to information and computer technology.

Nursing Informatics in Qatar

In 2006, the Nursing Informatics Department was established at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) which is the largest provider of health care in Qatar (dela Rosa, 2016). The department`s mission is “to provide advanced healthcare informatics practices, education and research through the effective use of health information technology” (Nursing informatics Department, 2015, p. 1). The Nursing Informatics Department has been instrumental in training and guiding nurses at HMC during the planning, design, and implementation process of the clinical information system (CIS) from 2013 to 2016 (dela Rosa, 2016).

Nurses and Nurse Managers at HMC

HMC has a diverse group of nurses and nurse managers. They come from different age groups, religions, cultures, educational backgrounds, and genders. As well, they have different informatics knowledge and skills. The nurse managers at HMC include Head Nurses and Charge Nurses. They manage the patient care units by directing, organizing, and developing clinical competencies either directly or indirectly through decisions about the nursing workforce and other patient care resources. As well, they manage budgets, and they must assure that the delivery of care is cost effective. Nursing leaders are also responsible for developing policies and procedures, protocols, and guidelines that establish the nursing standards at HMC ensuring that nurses adhere to an established Code of Professional Behaviour and Ethics. Overall, nurse managers are accountable to ensure that all nurses are knowledgeable and skilful in their speciality.

In 2013, nurses at HMC started to use healthcare advanced information technologies. They currently use electronic healthcare records that are integrated with clinical devices such as vital sign devices, cardiac monitors, glucometer devices, infusions pumps, medications dispensing machines, and barcoding devices. Nurses also use information and management systems in their daily practice, as they document, communicate, sort and retrieve data, and plan for care through the system.

Problem Statement and Significance

One of the Qatar National Health Strategies 2011-2016 goals is to promote the healthcare workforce by developing their skills to ensure the delivery of high quality care (Supreme Council of Health, 2015). This goal can be achieved by ensuring education and training for health professionals, so they will be able to contribute positively in meeting Qatar healthcare needs. Different researchers emphasize the importance of developing informatics competencies to enhance nurses’ informatics knowledge and skills that are relevant to their specific role (Darvish, Bahramnezhad, Keyhanian, & Navidhamidi, 2014; Eley et al., 2009; Garde, Harrison, Huque, & Hovenga, 2006).

Project Objectives

The broad goal of this project was to support informatics practice among nurses and nurse managers by enhancing their informatics knowledge and skills. The objectives of this project were to: (1) identify published informatics competency tools, (2) assess and compare existing tools developed for use with nurses and nurse managers, and 3) to provide recommendations for a pragmatic informatic competency tool(s) that can be administered to nurses and nurse managers in the context of Qatar.

Objective # 1:

To identify published informatics competency tools

Search Strategy

An electronic database search of the literature published from 2000 to 2016 was conducted using the following databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE, ERIC, and HealthSTAR – OVIDHealthstar. Keywords were “nursing informatics competenc*,” “informatics skill,” and “informatics knowledge”

The inclusion criteria used to screen the articles were 1) journal article published in English between 2000 to 2016, 2) tools developed for nurses (i.e. nurses and/or nurse managers). Exclusion criteria were 1) not published in English in a journal (e.g. dissertations), 2) published before 2000, and 3) the tool was not developed for nurses.

Search Results

The database search yielded 318 articles. Ninety articles met the inclusion criteria. Duplicates were removed and the articles’ title and abstracts were reviewed. The full texts for the remaining 35 articles were then reviewed for relevancy and 10 of these 35 articles were retained. Since only a small quantity of articles were identified, a manual search of reference lists of the 10 included articles was done, and two more articles were added. One of these articles was found online (grey literature) and the other article was found in the reference list of an article. The article found online was included in this review based on the fact that this tool was validated by two of the articles included in the review. The 12 retained articles were reviewed and distributed into two groups: four studies that applied informatics competency tools and eight studies that developed informatics competency tools.

Results

The results of the review will be presented in two sections 1) studies that applied an informatics competency tool, and 2) studies that described the development of an informatics competency tool.

Studies that Applied an Informatics Competency Tool

The main characteristics of these four articles are presented in Table 1. Hwang and Park (2011) conducted a quantitative study (N= 292 nurses, 28 nurse managers) to determine participant beliefs related to their use of informatics in practice. A tool based on Murphy et al.’s study (2004) was used which included seven core items (i.e. security /confidentiality, knowledge and information management, communication, clinical and service audit, clinical information system, and telehealth. More than one half of the nurses (69.2%) evaluated their informatics competency below average, and reported a need for informatics education. The results found significant positive relationships between informatics competencies and basic computer skills and informatics education. Negative relationships between informatics competencies, nurses’ age, and experience were found.

Yang et al. (2014) used a quantitative approach to measure the level of informatics competencies of 68 nurse managers and to determine the factors that influenced these competencies The survey included 49 informatic competency items identified by Hart (2010) (i.e. (1) 25 computer skills, (2) 20 knowledge and (3) 4 skills competencies). Responses were measured on a five-point Likert-type scale (i.e. no experience to expert skill). Cronbach’s alpha was greater than 0.85, which indicates high internal consistency. An ANOVA analysis was used to assess the differences among the three categories of informatics competencies. The results found that the participants’ informatics knowledge scores were significantly higher than their computer and informatics skill scores. A multiple linear regression analysis was used to assess the independent effects of the demographic variables on informatics competencies. The results found that education level, nursing administration experience, and informatics education or training had a significant impact on informatics competencies. In conclusion, Yang et al. (2014) recommended the importance of providing informatics education and training to improve nurse managers’ computer skills, informatics knowledge, and informatics skills.

Chung and Staggers (2014) conducted a quantitative, descriptive study to develop a tool to measure informatics competencies among 230 nurses and nurse managers in Seoul Korea (response rate = 99.1%; N = 228). This tool was designed to measure competencies on two levels of nursing practice: beginning and experienced levels. A total of 112 items were included in the questionnaire, which was based on Chang, Poynton, Gassert, and Staggers’s (2011) informatics competencies. The questionnaire collected data on socio-demographics, clinical factors (e.g., clinical experience), and nursing informatics competencies (e.g., skills and knowledge). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.98 which indicated high internal consistency. The results showed that participants scored higher on the informatics knowledge subscale compared to the computer and informatics skill subscales. The results also showed that some factors such as working in a managerial position, using computers at work, and having previous informatics or computer education had a significant effect on nursing informatics skills and knowledge. These findings suggested that informatics competencies need to be based on nurses’ needs and their level of practice.

Simpson (2013) used a qualitative ethnographic approach to study the lived experience of seven Chief Nurse Executives (CNEs) regarding their informatics competencies. Interviews focused on five themes that included technology knowledge, collaboration, health information technology selection, executive leadership, and standardization. The findings showed that the CNEs’ information technology knowledge and skills were not included nor considered in the evaluation and selection of the informatics competencies. CNEs stated, “their review responsibilities were limited to the functional level; that is looking at the systems features, rather than their ability to advance nursing practice” (Simpson, 2013, p. 284). Their role and abilities to be advocates and support nursing practice were restricted by the system.

Studies that Developed Informatics Competency Tools.

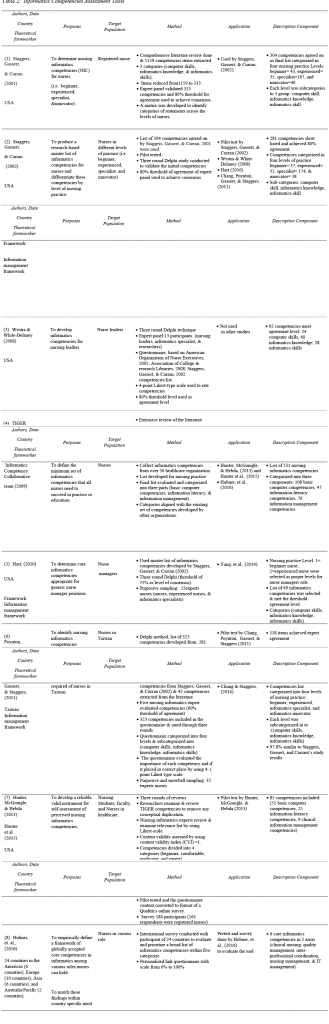

The main characteristics of these articles are presented in Table 2. Staggers, Gassert, and Curran (2001) conducted a study to develop a master list of informatics competencies based on the literature and to distinguish these competencies according to four levels of nursing practice: beginning nurse, experienced nurse, informatics expert, and informatics innovator. In order to identify informatics competencies, they conducted a search and identified 35 relevant articles published from 1986 to 1998. Based on a review of these articles, they extracted 1159 competencies. These competencies were revised and arranged under three categories: computer skills, informatics knowledge, and informatics skills. A panel of nursing informatics experts from the International Medical Informatics Association reduced the competencies from 1159 to 313 based on an 80% agreement threshold level. Then, the expert panel started to validate and categorise the accepted competencies across the levels of nursing practice. The final list of competencies included 304 items that met the agreement threshold. This list of 304 competencies was used in Staggers, Gassert, and Curran’s (2002) three round Delphi technique study. In this study, the authors aimed to develop a master list of informatics competencies for nurses in different levels of practice based on their 2001 work. The authors conducted a pilot study to identify any issues in the questionnaire before starting the main study. Purposive sampling was used to identify expert nurses in informatics as participants. Then, a three round Delphi approach was used and an 80% agreement threshold was set for accepting each competency in the final round. After accepting these competencies, the expert panel categorised the competencies into the appropriate nursing practice levels. The results showed that 92% of the total competencies were accepted, as 208 competencies were considered valid and distributed in four nursing practice levels. Each level was categorised into three subcategories: computer skills, informatics knowledge, and informatics skills.

Westra and White-Delaney (2008) based their work on the work of Staggers et al. (2002). The purpose of this work was to identify appropriate informatics competencies for nursing leaders. Based on a review of the literature, they complied a list of 119 competencies related to nurse leaders. A panel of 13 experts evaluated a questionnaire that included 119 informatics competency items rated on a four-point Likert-type scale. A three round Delphi approach was used and a threshold of 80% was set as a consensus level for panel agreement on competencies during the three rounds. The results recommended 92 informatics competencies to assess nurse managers’ competence.

In 2009, the TIGER Informatics Competency Collaborative team (TICC) was formed to develop and define a set of informatics competencies for all nurses and nursing students at different levels of practice (TIGER, 2009). The team conducted an extensive review of the literature and collected a list of informatics competencies from over 50 healthcare organizations. A final list of 231 items was categorized into three parts: 108 basic computer competencies, 47 information-literacy competencies, and 76 information management competencies.

Hart (2010) conducted a three round Delphi method study to assess and define the core informatics competencies needs for nurse managers. This author extracted competencies identified by Staggers, Gassert, and Currant in 2002. Participants included 25 expert nurses and in the first round, the expert panel agreed that the competencies in level one (beginner nurse) and level two (experienced nurse) were the most appropriate competencies for nurse managers. In round two, the panel validated all competencies based on the list of competencies of Staggers et al. (2002). A 75% threshold was set as a level of consensus for each competency. The final result identified 49 informatics competencies required for nurse managers that were categorized into three groups: computer skills, informatics knowledge, and informatics skills.

Chang, Poynton, Gassert, and Staggers (2011) applied a Delphi technique to identify informatics competencies required –by nurses in Taiwan. The authors used an informatics competencies questionnaire identified by Staggers, Gassert, and Currant in 2002, and 42 additional competencies extracted from the literature. These 323 competencies were divided into three main categories: computer skills, informatics knowledge, and informatics skills within four levels of nursing practice (i.e. beginner nurse, experienced nurse, informatics specialist, and informatics innovator). The authors used a web-based survey to collect data by email. A four-point Likert-type scale was used to measure participants’ opinions of the competencies and whether the competencies were placed in the right level of practice. During the three rounds, a threshold of 60% or greater was used as agreement level. The results showed that 318 informatics competencies required for nurses in Taiwan had 97.8% consensus with the results of the study conducted by Staggers et al. (2002).

In 2013, Hunter, McGonigle, and Hebda’s study aimed to develop a valid self-assessment tool of informatics competencies based on TIGER (2009) competencies for nurses, nursing students, and faculty. They used a six-step process to develop an instrument to assess nursing informatics competencies: First, each researcher reviewed the three sets of TIGER competencies to define and remove any conceptual duplication which lead to a reduction in the numbers of competencies in each set: 108 basic computer competencies were reduced to 99, information-literacy competencies were reduced from 47 to 42, and information management competencies were reduced from 76 to 12. Next, the nursing informatics experts reviewed the competencies and no changes were proposed. Next the experts reviewed each of the competencies to determine if it fit in the assigned category by assessing the behavioral verb of the item word. Then the experts reviewed the competencies to validate the relevancy of each competency by using a Likert-scale. Finally, the results were 1.0 for each competency set. This lead to reduction in the numbers of competencies in each set: basic computer competencies were reduced from 99 to 51, information-literacy competencies were reduced from 42 to 25, and information management competencies were reduced from 12 to 9. Each set of competencies was divided into four levels: beginner, comfortable, proficient, and expert. The authors used this instrument to conduct a survey to determine 161 registered nurses’ perceptions of their informatics competencies. The results lead to the development of a valid instrument that included 85 competencies. In addition, Hunter et al. (2015) retested this instrument and calculated Cronbach’s alpha for each set. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 for basic computer skills, 0.98 for information literacy, and 0.9 for clinical information management, which indicated high internal consistency.

Hubner et al.’s (2016) study was based on Egbert et al.’s (2016) study, which was focused on the TIGER competencies, Global Academic Curricula competencies, and Health Informatics Professional core competencies. Hubner et al. (2016) aimed to identify international core informatics competencies for various nursing roles and used a survey that included 24 competencies. A scale from 0% to 100% was used to rate the relevance of core informatics competencies based on five nursing areas: clinical nursing, quality management, inter-professional coordination, nursing management, and information technology management. The survey was sent to 72 experts from 24 countries and 41 participated. The results found that six core informatics competencies were accepted in each of the five nursing areas.

Objective # 2:

To Assess and Compare Existing Tools

Eight relevant articles that focused on developing informatics competency tools were reviewed and assessed using the following predetermined criteria developed by the authors : (a) psychometric properties, (i.e. reliability and validity of the tool) (Mokkink, Prinsen, Bouter, de Vet, & Terwee, 2016), (b) similarity and differences across the studies, such as the target population and competencies categories, and (c) the pragmatics of using the tool within the context of HMC (Fekete et al., 2011) as outlined in Table 3.

Psychometric Evaluation: Reliability

For this MN project, three criteria were used to evaluate the reliability of the tools:

- Stability of the tools was evaluated by checking the reported test-retest values.

- Internal consistency of the tools was evaluated by checking the reported Cronbach’s alpha.

- Equivalence of the tools was evaluated by checking the reported index of equivalence or expert agreement (Mokkink et al., 2016).

Evaluation results: Reliability

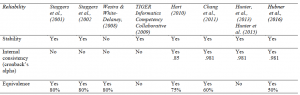

Stability

The authors in most of the studies indicated that their informatics competency tools were stable (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Hubner et. al., 2016; Hunter et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2015; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002; TIGER Informatics Competency Collaborative, 2009). There was one exception, the tool used by Westra and White-Delaney (2008) did not present stability in repeating measures. This was because the tool was not tested by the authors or retested in other studies.

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha for only three studies were identified, and all three tools showed high internal consistency more than 0.85 (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Hunter et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2015; Staggers et al., 2002). The highest Cronbach’s alpha test result was 0.981 for nursing informatics competencies required of nurses in Taiwan and developed by Chang et al. (2011). The authors in four of the studies did not mention that they did a Cronbach’s alpha measurement to assess the internal consistency of the tool.

Equivalence

The majority of the tools reported using threshold percentage as a base line for expert agreement (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Hubner, et. al., 2016; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002; Westra & White-Delaney, 2008). Table 4 illustrates if the authors reported the three selected criteria.

Psychometric Evaluation: Validity

Three criteria were used to evaluate the validity of the tools:

- Content validity of the tools was evaluated by checking if the authors reported on the relevance of the content to the given context.

- Criterion validity of the tools was evaluated by checking if the authors reported on the correlation of the tool with other variable measurements.

- Construct validity of the tools was evaluated by checking if the tool aligned with the proposed theoretical or conceptual predictions and that the tool measured what it claimed to measure (Mokkink et al., 2016).

Evaluation results: Validity

Content validity. All the studies measured content validity through expert agreement or by doing a content validity index (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Hubner, et. al., 2016; Hunter et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2015; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002; TIGER Informatics Competency Collaborative, 2009; Westra & White-Delaney, 2008).

Criterion validity. Only two studies measured the correlation of the tool with other variables such as education level, experience of nursing administration work, and having or not having informatics or computer education or training (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010).

Construct validity. All of the studies mentioned that they assessed construct validity. All of the tools were based on previous research. Only three studies mentioned that their tool development was guided by a conceptual framework (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Staggers et al., 2002). Table 5 illustrates whether the authors addressed the three criteria in their study.

Similarity and Differences Across Studies

The majority of the informatics competency tools were applied in the USA, except for one study that was done in Taiwan and another international study that included 24 countries. No studies were done in the Middle East. The majority of tools were applied in current studies within the past 10 years ago, except two studies were conducted in 2001 and 2002. These were included because other studies were based on these older studies.

The results showed that four studies were based on Staggers et al.’s (2001) study and two studies were based on the TIGER (2009) study. Five studies used Delphi technique as the method to validate the informatics competencies (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Hunter et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2015; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002; Westra & White-Delaney, 2008), while the TIGER Informatics Competency Collaborative (2009) conducted an extensive review and Hubner et al. (2016) conducted an international survey.

The tools were also assessed for the following factors: (a) target population and level of practice, such as beginner nurse or experienced nurse and (b) length and complexity of each tool.

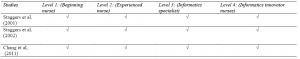

Target population and level of practice

Three tools (Chang et al., 2011; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002) were developed to assess nurses’ informatics knowledge and skills in four levels of nursing practice. These levels included (a) beginner nurse, (b) experienced nurse, (c) informatics specialist, and (d) informatics innovator nurses (Chang et al., 2011; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002). The authors defined the four levels similarly. The beginning nurse has basic information, management knowledge and skills that will help her or him to use existing technology in direct nursing practice. The experienced nurses are those who utilize the information and retrieve information from the system, such as educators and managers. Those competencies identified for informatics specialists include nurses with advanced specialty education who can innovate, conduct informatics research, and develop informatics theory (Chang et al., 2011; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002). Table 6 illustrates each of the studies and the target population based on level of practice.

In contrast, two studies developed competency tools specifically for nurse managers (Hart, 2010; Westra & White-Delaney, 2008). These two studies were based on the work of Staggers et al. (2002). On the other hand, Hubner et al. (2016) classified informatics practices as follows: clinical nursing, quality management, inter-professional coordination, nursing management, and information technology management. Each level was then subcategorized into six core informatics competencies. The remaining two studies developed an informatics competency tool for all nurses regardless of their practice level (Hunter et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2015; TIGER Informatics Competency Collaborative, 2009). Table 7 below illustrates what specific target population each tool was developed for.

Informatics competency tool categories

There were similarities and differences in the categories of the competencies themselves. The results showed that the majority of the tools were classified into three major categories: (a) computer skill, (b) informatics knowledge, and (c) informatics skill (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002; Westra & White-Delaney, 2008).

The terminology used to describe the domains of the tools in four of the studies was different; that is, the authors referred to the categories as (a) basic computer, (b) information literacy, and (c) information management competencies (Hunter et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2015; TIGER Informatics Competency Collaborative, 2009). Hubner et al. (2016) did not classify the competencies per domain category; rather, they listed six core competencies in each level. Table 8 illustrates the major categories assessed by the authors across the studies.

Practicality and Feasibility

In order to assess the informatics competency tools practicality for use in HMC, it was important to assess the language clarity by reading the items to determine if they would be understood by a non-native English speaker. This assessment demonstrated my own subjectivity in assessing the practicality of these tools. The results show that the majority of the competency tools were written in a clear way. However, Hubner et al.’s (2016) tool was unclear as the tool demonstrates core competencies, such as nurses’ documentation and information knowledge management, without identifying the competency items under each core competency.

The length of the informatics competency tools was another important criteria to assess the usefulness of the tool in order to prevent potential response burden. The results showed variety in tool length. Chang et al. (2011) recommended 318 competencies (highest numbers of competencies) and Hubner et al. (2016) recommended 30 competencies (lowest numbers of competencies). Both tools were developed for different levels of nursing practice. As discussed previously, the majority of these tools were developed for specific nurse practice levels and specific competencies that meet the needs of each level. For example, Staggers et al.’s (2001) informatics competency tool was divided into four levels: beginner with 43 competencies, experienced with 35 competencies, specialist with 187 competencies, and innovator with 40 competencies. On the other hand, TIGER’s (2009) tool was developed for all nurses without specification for level of practice and included 281competenices.

Finally, it was important to consider if these tools had been applied and validated in other studies. The results showed that the majority of these tools had been applied and validated in other studies (Chang et al., 2011; Hart, 2010; Staggers et al., 2001; Staggers et al., 2002; TIGER Informatics Competency Collaborative, 2009). However, three tools had not been applied or validated in another study (Hubner et al., 2016; Hunter et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2015; Westra & White-Delaney, 2008). Table 9 illustrates the level of practice, total number of items, items per practice level, language clarity, and prior validation of each tool.

Objective # 3:

To Provide Recommendations for a Pragmatic Competency Tool for Future Application at HMC

Recommendations:

Two informatics competency tools are recommended for application at HMC. To measure nurses’ informatics competencies, the tool developed by Chang et al. (2011) is recommended. This recommendation is based on the following strengths

- The tool was based on the informatics competencies tool developed by Staggers, Gassert, and Curran (2002).

- The validity and reliability of this tool (level 1 and 2) were retested by Chung and Staggers (2014), and the results showed Cronbach’s ?= 0.981 and R > 0.90.

- However, the recommendation is to use only the items in level 1 for nurses, because using all the 112 items in both level 1 and level 2 could cause response burden for nurses completing the survey As well, Staggers et al. (2002) demonstrated that level 2 is more appropriate to measure nurses with proficiency in education or administration. This typically does not reflect the roles and responsibilities of most staff nurses at HMC.

For nurse managers, the tool developed by Hart (2010) is recommended because of the following strengths

- This tool was developed specifically for nurse managers. The tool was revalidated by Yang et al., (2014) and showed high reliability (Cronbach’s ? higher than 0.85).

Other key recommendations for practice are listed below:

- Develop a committee of experts in informatics at HMC in order to provide feedback on the two recommended tools, as well as the pragmatics of future application of these tools at HMC.

- Conduct pilot studies and psychometric testing using the recommended tools. The target population will include staff from the nursing informatics department, nurses, and nurse managers.

- Conduct a main study with a larger sample at HMC to measure nurses’ and nurse managers’ informatics competencies.

- Develop future resources and strategies based on the study results; for example, tailored education and training sessions to enhance nurses’ and nurse managers’ informatics competencies at HMC.

Limitations

This review of informatics competencies tools has limitations. First, there were limited studies that focused on measuring informatics competencies for nurse managers. Hence, the evaluation and selection of the optimal tool for use in HMC was limited. Second, some studies selected in this review included participants from different levels of practice such us nurses, educators, researchers, and informatics specialists. This makes comparisons across studies difficult. Third, the grey literature was not searched. Hence some tools and relevant literature may have been missed.

Conclusion

This MN project conducted an analysis of published informatics competency tools so that recommendations could be made about a pragmatic tool for use at HMC in Qatar. Two tools can be applied to measure nurses’ (Chang et al., 2011) and nurse managers’ (Hart, 2010b) informatics competencies at HMC. Since these tools have not been applied in Qatar or other Middle Eastern countries, future feasibility and validation studies are needed as well as larger studies to examine nurses and nurse managers’ informatics competencies

References

Ammenwerth, E., Rauchegger, F., Ehlers, F., Hirsch, B., & Schaubmayr, C. (2011). Effect of a nursing information system on the quality of information processing in nursing: An evaluation study using the HIS-monitor instrument. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 80(1), 25-38. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.10.010

Bowcutt, M., Rosenkoetter, M. M., Chernecky, C. C., Wall, J., Wynn, D., & Serrano, C. (2008). Implementation of an intravenous medication infusion pump system: implications for nursing. Journal of Nursing Management, 16(2), 188-197. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00809.x

Buntin, M. B., Burke, M. F., Hoaglin, M. C., & Blumenthal, D. (2011). The benefits of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Affairs, 30(3), 464-471. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0178

Chang, J., Poynton, M., Gassert, C., & Staggers, N. (2011). Nursing informatics competencies required of nurses in Taiwan. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 80(5), 332-340. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.01.011

Chung, S. Y., & Staggers, N. (2014). Measuring Nursing Informatics Competencies of Practicing Nurses in Korea. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 32(12), 596-605. doi:10.1097/CIN.0000000000000114

Crist-Grundman, D., & Mulrooney, G. (2011). Effective Workforce Management Starts With Leveraging Technology, While Staffing Optimization Requires True Collaboration. Nursing Economics, 29(4), 195-200.

Darvish, A., Bahramnezhad, F., Keyhanian, S., & Navidhamidi, M. (2014). The role of nursing informatics on promoting quality of health care and the need for appropriate education. Global Journal of Health Science, 6(6), 11-18. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p11

dela Rosa, S. A. (2016). Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) Embracing Technological Innovation in Health Care through Nursing Informatics. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 11(1), 1-3.

Egbert, N., Thye, J., Schulte, G., Liebe, J., Hackl, W. O., Ammenwerth, E., & Hübner, U. (2016). An Iterative Methodology for Developing National Recommendations for Nursing Informatics Curricula. Studies In Health Technology And Informatics, 228, 660-664.

Eley, R., Soar, J., Buikstra, E., Fallon, T., & Hegney, D. (2009). Attitudes of Australian nurses to information technology in the workplace: a national survey. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 27(2), 114-121.

Fekete, C., Boldt, C., Post, M., Eriks-Hoogland, I., Cieza, A., & Stucki, G. (2011). How to Measure What Matters: Development and Application of Guiding Principles to Select Measurement Instruments in an Epidemiologic Study on Functioning. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 90S29-38. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e318230fe4.

Garde, S., Harrison, D., Huque, M., & Hovenga, E. S. (2006). Building health informatics skills for health professionals: results from the Australian Health Informatics Skill Needs Survey. Australian Health Review: A Publication Of The Australian Hospital Association, 30(1), 34-45.

Graves, J. R., & Corcoran, S. (1989). The study of nursing informatics. The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 21(4), 227-231.

Hart, M. D. (2010). A Delphi study to determine baseline informatics competencies for nurse managers. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 28(6), 364-370. doi:10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181f69d89

Hart, M. D. (2010b). A Delphi study to determine baseline informatics competencies for nurse managers. Retrieved from http://tigercompetencies.pbworks.com/ f/Nurse+Manager+Informatics+Competencies.pdf

Hubner, U., Shaw, T., Thye, J., Egbert, N., Marin, H., & Ball, M. (2016). Towards an International Framework for Recommendations of Core Competencies in Nursing and Inter-Professional Informatics: The TIGER Competency Synthesis Project. Studies In Health Technology & Informatics, 228, 655-659. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-678-1-655

Hunter, K. M., McGonigle, D. M., & Hebda, T. L. (2013). TIGER-based measurement of nursing informatics competencies: The development and implementation of an online tool for self-assessment. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 3(12), 70.

Hunter, K., McGonigle, D., Hebda, T., Sipes, C., Hill, T., & Lamblin, J. (2015). TIGER-Based Assessment of Nursing Informatics Competencies (TANIC). In New Contributions in Information Systems and Technologies, 1, 171-177.

Hwang, J., & Park, H. (2011). Factors associated with nurses’ informatics competency. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 29(4), 256-262. doi:10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181fc3d24

Lin, H., Hsu, M., & Yang, C. (2014). The influences of computer system success and informatics competencies on organizational impact in nursing environments. Computers, Informatics, Nursing: CIN, 32(2), 90-99. doi:10.1097/CIN.0000000000000010

Lucero, R. J., Haomiao, J., De Cordova, P. B., & Stone, P. (2011). Information Technology, Nurse Staffing, and Patient Needs. Nursing Economic$, 29(4), 189-194.

Mason, J. J., Roberts-Turner, R., Amendola, V., Sill, A. M., & Hinds, P. S. (2014). Patient Safety, Error Reduction, and Pediatric Nurses’ Perceptions of Smart Pump Technology. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(2), 143-151. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2013.10.001

Mays, C. H., Kelley, W., & Sanford, K. (2008). Keeping up: the nurse executive’s present and future role in information technology. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 32(3), 230-234. doi:10.1097/01.NAQ.0000325181.94589.a6

Mokkink, L. B., Prinsen, C. C., Bouter, L. M., de Vet, H. W., & Terwee, C. B. (2016). The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy / Revista Brasileira De Fisioterapia, 20(2), 43-51. doi:10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0143.

Murphy, J. (2010). Nursing informatics: the intersection of nursing, computer, and information sciences. Nursing Economic$, 28(3), 204-207.

Murphy, J., Stramer, K., Clamp, S., Grubb, P., Gosland, J., & Davis, S. (2004). Health informatics education for clinicians and managers–what’s holding up progress?. International Journal Of Medical Informatics, 73(2), 205-213.

Nursing informatics Department. (2015). Vision and Mission Statements. Nursing Informatics Bulletin. 1(1), 1-11.

Piscotty, R. J., & Tzeng, H. (2011). Exploring the clinical information system implementation readiness activities to support nursing in hospital settings. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 29(11), 648-656. doi:10.1097/ NCN.0b013e31821a153f

Piscotty, R. J., Kalisch, B., & Gracey-Thomas, A. (2015). Impact of Healthcare Information Technology on Nursing Practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(4), 287-293. doi:10.1111/jnu.12138

Schleyer, R. H., Burch, C. K., & Schoessler, M. T. (2011). Defining and integrating informatics competencies into a hospital nursing department. Computers, Informatics, Nursing: CIN, 29(3), 167-173. doi:10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181f9db36

Simpson, R. L. (2013). Chief Nurse Executives Need Contemporary Informatics Competencies. Nursing Economic$, 31(6), 277-288.

Staggers, N., Gassert, C., & Curran, C. (2001). Informatics competencies for nurses at four levels of practice. Journal of Nursing Education, 40(7), 303-316.

Staggers, N., Gassert, C., & Curran, C. (2002). A Delphi study to determine informatics competencies for nurses at four levels of practice. Nursing Research, 51(6), 383-390.

Supreme Council of Health. (2015). Qatar National Health Strategies 2011-2016. Retrieved from http://www.nhsq.info/app/media/2908

Sweis, R. J., Isa, A., Azzeh, H., Shtyh, B., Musa, E., Aibtoush, R. M. (2014). Nurses’ resistance to the adoption of information technology in Jordanian hospital. Life Science Journal, 11(4), 8-18.

Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER). (2009). The TIGER initiative informatics competencies for every practicing nurse: Recommendations from the TIGER collaborative. Retrieved from http://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-himss/files/production/ public/FileDownloads/ tiger-report-informatics-competencies.pdf

Turner, M., Kitchenham, B., Brereton, P., Charters, S., & Budgen, D. (2010). Does the technology acceptance model predict actual use? A systematic literature review. Information & Software Technology, 52(5), 463-479

Westra, B., & White-Delaney, C. (2008). Informatics competencies for nursing leaders. Nursing Outlook, 55(4), 210-211.

Wulff, K., Cummings, G. G., Marck, P., & Yurtseven, O. (2011). Medication administration technologies and patient safety: a mixed-method systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(10), 2080-2095. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05676.x

Yang, L., Cui, D., Zhu, X., Zhao, Q., Xiao, N., & Shen, X. (2014). Perspectives from nurse managers on informatics competencies. Scientific World Journal, 2014, 1-5. doi:2014/391714

Biographical Statement:

Rawda Abdulla Ali is a Nursing Informatics Coordinator at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Qatar. Ms. Rawda had previous experience and works as nurse, charge nurse, and Head Nurse at HMC. She recently completed a Master in Nursing Degree from the University of Calgary in Qatar.

Kathleen Benjamin is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Calgary in Qatar. She teaches and supervises students in the MN program. Her program of research focuses on the promotion of active living and healthy diets for adults as well as topics related to nursing practice and education.

Dr. Sadia Munir is an instructor in the Electives faculty at the University of Calgary in Qatar. She earned her doctoral degree in molecular endocrinology from York University, Toronto, Canada. Her academic and research training is in molecular and epidemiological studies focusing on maternal and foetal health.

Noha Saleh is a Nursing Informatics Coordinator at Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar. She received her M.D. from Alexandria University, Egypt. Eventually she earned a postgraduate diploma in computer applications, at Annamalai University, India. She spent eleven years of her career as a clinical instructor in the faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University.