Gender and sex data practices within electronic health records in a primary care setting: A use case approach

by Drew B. A. Clark, PhD, HEC-C, RCC

Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia

Lindsay MacNeil, MSc

Senior Business Analyst, Trans Care BC, Provincial Health Services Authority

Lorraine Grieves, MA, RCC

Provincial Program Director, Trans Care BC, Provincial Health Services Authority

Marria Townsend, MD, CCFP

Medical Director, Trans Care BC, Provincial Health Services Authority

Citation: Clark, D. B. A., MacNeil, L., Grieves, L. Townsend, M. (2022). Gender and sex data practices within electronic health records in a primary care setting: A use case approach. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 18(1). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=10866

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to articulate a process through which healthcare organizations can identify how to approach gender and sex data collection within electronic health records (EHRs) to support delivery of high-quality care for Two-Spirit, transgender, and nonbinary people. Based on guiding principles, a review of literature, and consultation with interested parties, we developed a model process for determining gender and sex data practices for organizational EHRs that balance the needs of care participants, healthcare providers, and administrators.

We selected a primary care setting as our example, due to the broad range of care provided and referrals made. We illustrate a six-step process for assembling a team, identifying guiding principles, generating use cases and user stories, drafting data categories and response options, conducting consultation with interested parties, and making context-specific recommendations. Detailed recommendations for gender and sex data collection categories, response options, and implementation within a primary care setting are provided.

The proposed use case approach was useful for identifying gender-affirming, patient-centered, privacy-focused, culturally safe gender and sex data collection within a primary care setting. This use-case approach may be applied within diverse care settings and various social, political, and legal contexts to create EHRs tailored to the needs of specific organizations and communities.

Keywords: Electronic Health Records; Health Equity; Primary Health Care; Transgender Persons; Two-Spirit Persons

Introduction

Collection of gender and sex data through electronic health records (EHRs) can support the health and wellbeing of Two-Spirit[1], trans and non-binary (TTNB) people through informing the care of individual patients and addressing population-level health disparities. The mistreatment that TTNB people often experience in healthcare settings creates barriers to accessing necessary healthcare and contributes to inequitable health outcomes within this population (Callahan et al., 2014; Deutsch et al., 2013). EHRs play an important role in the quality of patient care, for example, failure to appropriately collect data related to patient gender and sex can lead to invisibility, misnaming, mispronouncing, stigmatization, and violence for TTNB patients within care settings, and ultimately result in avoidance of care (Alpert et al., 2022; Callahan et al., 2014; Deutsch et al., 2013; Deutsch & Buchholz, 2015; Dunne et al., 2017; Kutscher, 2016; Samuels et al., 2018). Recently, data fields, response options, and information displays within electronic health records (EHRs) themselves have been identified as factors increasing barriers to care for TTNB populations (Safer, 2019; Samuels et al., 2018). Additionally, clinical care may be compromised by data accuracy issues related to confusion around appropriate ranges for blood tests for those on gender-affirming medications and the documentation, or lack thereof, of organs that are present, surgically modified, or removed (Alpert et al., 2022; Deutsch et al., 2013; Kutscher, 2016; Samuels et al., 2018). Finally, administrative errors may result from inadequate gender and sex data practices when billing insurance for sex-specific procedures (e.g., prostate screening) (Kutscher, 2016; Salyer, 2017). Given the substantial health disparities experienced by TTNB populations, the role of many ciscentric EHR data fields in increasing barriers to care for TTNB populations brings about an ethical obligation and a call to action to address gender and sex data practices at a systems level (Callahan et al., 2014).

[1] “The term Two-Spirit was created by a group of LGBTQ Indigenous community members in 1990 at the third annual Inter-tribal Native American, First Nations, Gay and Lesbian American Conference held in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It is a term currently used within some Indigenous communities to encompass sexual, gender, cultural and spiritual identity. Two-Spirit reflects complex Indigenous views of gender roles and the long history of sexual and gender diversity in many Indigenous communities. Individual terms and roles for Two-Spirit people are specific to each community. The term Two-Spirit is only to be used for Indigenous people, due to the cultural and spiritual context, however, not all Indigenous people who hold diverse sexual and gender identities consider themselves to be Two-Spirit.” (Trans Care BC, 2021, p. iii)

Several practices to improve the collection of gender and sex data within electronic health records have been identified in previous publications. Recommended data collection practices include gathering gender- and sex-related demographic data, allowing patients to self-report this data, and ensuring patients are easily able to change gender-related information without compromising the integrity of the medical record (Deutsch et al., 2013; Deutsch & Buchholz, 2015; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, 2011; Kronk et al., 2022; Samuels et al., 2018). Key data categories identified in the literature include name used, pronouns used, gender, and sex assigned at birth, as well as administrative/legal sex when required for billing purposes (Deutsch et al., 2013; Deutsch & Buchholz, 2015). Consistent with broader gender and sex data collection practices, a two-step gender and sex data collection method has been proposed within EHRs, in which two separate questions are asked, first about gender identity and second about sex-assigned at birth (Deutsch et al., 2013; Deutsch & Buchholz, 2015; Kronk et al., 2022; Vance & Mesheriakova, 2017). Adequate options should be provided for gender (e.g., nonbinary) and sex assigned at birth (e.g., intersex) (Dunne et al., 2017; Shenoy et al., 2014).

It is important that when Two-Spirit is provided as a gender response option, that it should only be available to Indigenous (e.g., Native American, First Nations, Inuit, Métis) people (Bates et al., 2022). In the care of TTNB patients, it is also particularly important to maintain an inventory of current anatomy as well as gender-related medical history (e.g., hormone therapy) (Deutsch et al., 2013; Grasso et al., 2021; Kronk et al., 2022). Billing issues that arise due to sex-specific billing practice (e.g., cervical and prostate screening) can be addressed by basing care and insurance coverage on anatomy, rather than gender or sex (Deutsch et al., 2013). In addition to implications for individual care, collection of accurate gender and sex data is increasingly recognized as demographic information necessary for analyzing how intersecting identity factors shape health equity and experiences related to health policies and programs (e.g., gender-based analysis plus) (Government of Canada, 2018). EHRs can play a critical role in the collection of data to support improved policy, programming, and health outcomes for people of all genders, and TTNB populations in particular.

Gender and sex data practices within EHRs extend beyond data fields and carry ethical implications for nurses and other healthcare professionals. TTNB people are at risk of unique harms stemming from privacy breaches of gender and sex data, harms which disproportionately impact racialized TTNB individuals (Thompson, 2016). Systems and protocols must be developed to protect patient privacy through appropriate data security (Callahan et al., 2014). While standard collection of gender and sex data from all patients may seem ideal from systems, research, or clinical care perspectives, the rights of patients to choose what information they disclose and to control whether that information in recorded in EHRs is important to recognize (Callahan et al., 2014; Dunne et al., 2017; Samuels et al., 2018). Once gender and sex data are collected, name used, pronouns, and gender should be visible in EHRs to nurses and others interacting with patients, while administrative/legal names and sex should be stored separately (e.g., if necessary for billing) to prevent harm from misnaming, mispronouning, and misgendering (Deutsch et al., 2013; Dunne et al., 2017; Samuels et al., 2018). Despite the critical importance of privacy related to sex-assigned at birth, few EHRs are built with this functionality in mind. Staff using EHR systems must also possess the TTNB cultural safety awareness and skills necessary to collect, use, and manage gender and sex data (Callahan et al., 2014; Kronk et al., 2022; Samuels et al., 2018; Shenoy et al., 2014; Vance & Mesheriakova, 2017). To date, absence of TTNB cultural safety has been a distinct barrier to implementation of improved gender and sex data collection practices (Kutscher, 2016). Due to these EHR-based barriers that TTNB patients currently face in accessing healthcare, efforts to make relevant systems-level changes must be prioritized to reduce harm. Attention must be paid to the inclusion of TTNB voices in system design, development of patient experience reporting mechanisms, delivery of TTNB cultural competency training to nurses and healthcare staff (Callahan et al., 2014; Dunne et al., 2017; McClure et al., 2021; Samuels et al., 2018; Shenoy et al., 2014; Vance & Mesheriakova, 2017).

While many recommendations have been made to improve the integration of gender and sex data into EHRs, implementation of such changes has been limited. Over the past three years, we have responded to multiple requests for support in developing better practices for gender and sex data collection in EHRs, and through this work, we identified the need to bridge understanding among those tasked with the technical aspects of EHR design and system users, both healthcare providers and patients. The purpose of this paper is to articulate a process through which organizations can identify approaches to ethical and culturally safer gender and sex data collection within EHRs necessary for delivery of equitable, high-quality care.

Method

In formulating our approach to gender and sex data practices, we considered three user groups: patients, healthcare providers, and administrators. To address the historical and ongoing oppression of TTNB communities, mistreatment within healthcare settings, and mistrust of healthcare systems and providers, we primarily centered the needs of TTNB patients. Our goal was not to modify or redesign an existing EHR system, nor to provide data standard recommendations that could be universally applied, but rather to identify gender and sex data practices that would address the needs of TTNB patients. Data practices refer to all aspects of data collection, use, and management. We recognized that both EHRs and gender and sex data needs vary across care settings (e.g., primary care, community-based counselling), and that collection/disclosure of data that is unnecessary in a particular setting could put TTNB participants at risk of harm while serving no clinical function. However, we also recognized the value of collecting data to support sex- and gender-based analysis for administrative purposes (e.g., research, program evaluation). Therefore, we sought to develop a model process for determining the best gender and sex data practices for an organization that would balance the needs of care participants, healthcare providers, and administrators within their practice context (e.g., disciplinary, social, political). We selected a primary care setting in British Columbia, Canada as our example, as primary care encompasses physical, mental, and sexual/reproductive health care, as well as referrals to external providers, making collection of a range of gender and sex data potentially necessary.

In the discipline of business analysis, use cases and user stories are techniques employed to aid in communicating the requirements of a solution, often in the context of developing software. Use cases are descriptions of observable interactions between actors and solutions that result from actors accessing a system to achieve a goal (International Institute of Business Analysis, 2015). A user story constitutes a brief description of functionality or quality required to deliver value to an interested party (International Institute of Business Analysis, 2015). We centered cases and user stories to support a patient-centered approach and identify opportunities to promote gender-affirmative care, privacy, and cultural safety.

Our process for determining best gender and sex practices within an EHR involved six steps. The first step was to assemble a team with expertise related to: clinical care of TTNB patients; health informatics and/or health systems design; privacy, ethics, human rights, and/or law; and lived/living experience. The second was to establish guiding principles relevant to the process. The third was development of use cases and user stories as a means of determining what gender- and sex-related data are required. The fourth step was to develop data categories and response options to elicit necessary data. Fifth, was to engage in consultation with system users (i.e., patients and clinicians) for validation of use cases and data practices. Data categories and response options initially developed in step four were revised based on feedback from consultation sessions; the revised categories and options are presented in the results section. The sixth step was to make recommendations for EHR data practices and staff training necessary for successful implementation based on team member and system user input.

Results

Step 1: Team

The core team included Two-Spirit, trans, non-binary, and cisgender individuals bringing expertise in medicine, nursing, counselling, ethics, health care administration, and health informatics who had been providing feedback to multiple groups on gender and sex data collection in EHRs as part of their work within a transgender health program. The four team members met approximately every other month over the course of two years, with team members carrying out various responsibilities, such as reviewing literature, engaging system users, and conducting consultation sessions.

Step 2: Principles for gender and sex data practices

Trans Care BC, at the Provincial Health Services Authority, is the organization responsible for planning, coordinating, monitoring, and improving health care and community supports for TTNB people across the province of British Columbia, Canada (Trans Care BC, 2020). Our program takes a gender-affirming approach to promoting the health and wellbeing of TTNB populations, an orientation aligned with internationally recognized best practices for the care of transgender individuals (Coleman et al., 2012). The overarching guiding principles for care of TTNB individuals within our organization are gender-affirming care inclusive of non-binary identities; accountable; transparent; anti-oppressive; trauma-informed; collaborative; person-centered; equitable; and accessible. We drew on these guiding principles to establish the following principles to guide gender and sex data practices within EHRs: (1) person-centered; (2) gender-affirming; (3) privacy-focused; and (4) culturally safe.

Equitable, accessible, person-centered care of TTNB patients is dependent on accurate data collection. In addition to collecting data necessary for respectful care (i.e., names and pronouns used), accurate anatomical and hormone information may be required for clinical care. TTNB patients deserve equitable access to care settings where their names and pronouns are respected, and their medical information is accurately recorded and used to deliver optimal medical care.

Gender-affirming data practices facilitate dignified and respectful treatment of TTNB patients (e.g., use of appropriate names and pronouns). Gender is a personal attribute that must be voluntarily identified by the patient. Gender and sex data must be collected in a manner that is affirming of patient gender, including non-binary genders and Two-Spirit identities. The practices must convey understanding of gender, sex, and other culturally relevant constructs through use of appropriate language. It is understood that language is context-specific and evolves over time, necessitating ongoing work to ensure accuracy of language and harmonization amongst systems.

Privacy of health and personal information is paramount in ensuring the safety of TTNB patients (e.g., reducing the risk that disclosure of TTNB status will result in discrimination, denial of care, or violence in healthcare settings). Transparency regarding privacy practices is necessary for accountability and fostering trust among TTNB patients. Gender and sex data must be shared voluntarily with consent given to record these data in EHRs. Patients must maintain control of their personal data, and this must be prioritized over the preferred data practices of healthcare providers, administrators, or researchers.

Trans cultural safety can be supported or undermined by EHR design and implementation. For example, EHRs can support trans cultural safety through the collection of accurate information and use of data to treat TTNB patients with respect and to ensure access to optimal clinical care. Additionally, in the collection and stewardship of Indigenous trans and Two-Spirit data, anti-racist, Indigenous cultural safety practices must be centred alongside cultural safety practices attuned to gender diversity. To promote cultural safety in all healthcare interactions, EHR data practices must be supported through training of all staff responsible for eliciting, using, and managing data, as well as those involved in system design.

Step 3: Use cases and user stories

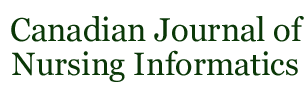

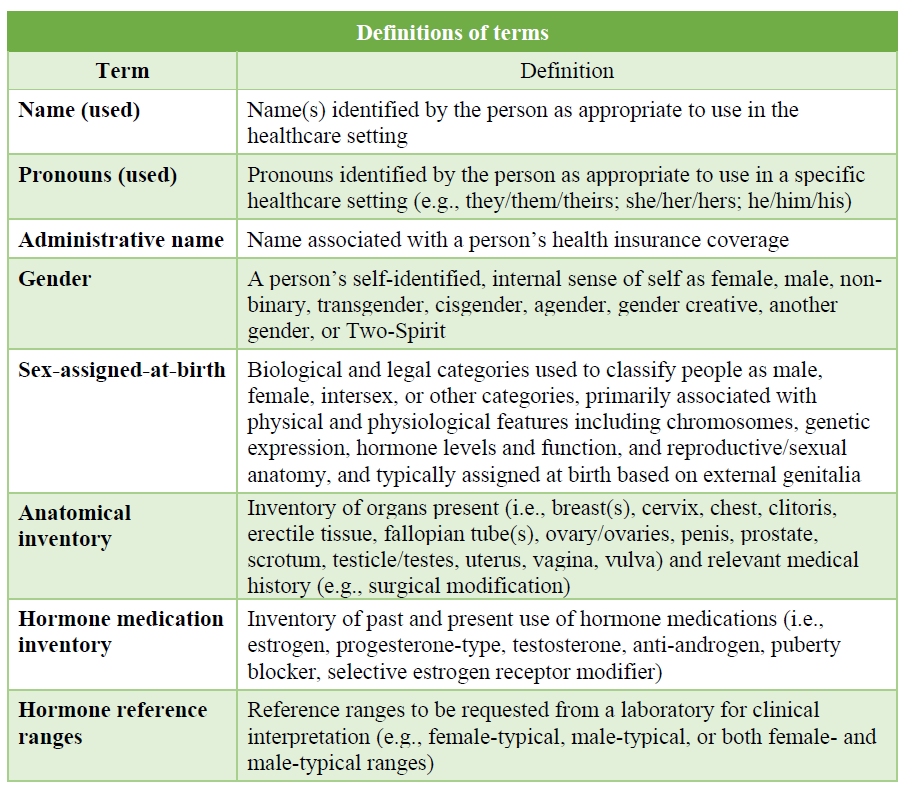

We generated nine high-level use cases based on common business processes within a primary care setting. We first developed a primary care clinical encounter use case, then formulated secondary clinical use cases that flowed from this case (i.e., prescriptions, laboratory, imaging, referral). Subsequently, we developed administrative cases (i.e., intake, billing, research, registration), ending with registration, to ensure the required data (and no unnecessary data) were collected at appropriate junctures in the care journey. Through the use case analysis process, nine gender and sex data elements were identified and defined, based on current usage and application within the context of EHRs (Table 1). For example, the component of the larger construct of gender sometimes referred to as ‘gender identity’ (as opposed to ‘gender expression’ or ‘gender roles’) is the component relevant within EHR data categories, and therefore the element described in Table 1 under ‘gender’. Descriptions of each use case and a corresponding list of gender and sex data categories necessary to achieve the described goals are provided (Table 2).

Table 1. Definitions of terms

Table 2. Use Case Gender and Sex Data Requirements

The following user stories developed to illustrate processes which may involve gender and sex data use in primary care. Primary care was selected as an ideal scenario due to the numerous processes within primary care which involve sex and gender data practices that can compromise the care of TTNB patients.

Intake and booking

Carlos calls a clinic, stating that he is new to the area and would like to be become a primary care patient. The clinic is accepting new patients, so a staff member schedules an intake appointment and records his name and phone number.

Registration

Carlos is greeted at the clinic and asked to complete the registration process using a private computer kiosk. Each page of the registration form indicates why information is being collected and whether it is required or optional. Carlos confirms that the name and phone number on file are correct and adds both physical and email addresses. Carlos enters information required for billing (i.e., health insurance number, administrative name) and chooses to indicate pronouns of he/him/his. He also chooses to share optional demographic data including gender (i.e., transgender, male) and sex-assigned-at-birth (i.e., female). On the medical history form, Carlos indicates he has been diagnosed with type II diabetes, had a hysterectomy six years ago, and is currently taking testosterone. The reasons for his visit are for investigation of a foot injury and a refill of his testosterone prescription.

Clinical encounter

The nurse practitioner (NP) has reviewed the information Carlos entered in the registration system. Together, they go over his medical history and complete the anatomical inventory (e.g., presence or absence of uterus) and hormone medication inventory (e.g., testosterone use). The NP examines Carlos’s foot, is unable to determine the cause of his ongoing pain and recommends an x-ray to determine if he has a fracture and whether a referral to an orthopedist is needed. Based on the information Carlos provides about the dosage and length of time on testosterone, the NP is comfortable writing a short-term prescription while Carlos completes blood work. The NP asks Carlos if he has any other medical concerns and lets him know that the clinic supports patients to access a broad range of gender-affirming medical and psychosocial supports. Carlos accepts the NP’s recommendations for blood work and x-rays, and they discuss what identifying information (i.e., name, pronouns) should be communicated to external providers (i.e., lab, imaging, specialist).

Prescription

The NP sends a prescription to the pharmacy, including instructions (per patient’s request) to refer to the patient as Carlos and to use he/him/his pronouns. Administrative name is also provided with Carlos’s permission for medical record-keeping and billing purposes. Carlos fills his prescription and is referred to with correct name and pronouns.

Laboratory

The NP sends a requisition to the laboratory, including instructions to refer to the patient as Carlos and to use he/him/his pronouns. Administrative name is also provided with Carlos’s permission for medical record-keeping and billing purposes. Typical male reference ranges are requested by the NP due to the length of time Carlos has been on testosterone. Carlos completes his laboratory tests and is referred to with correct name and pronouns.

Imaging

The NP gives Carlos an order for an x-ray with his name and pronouns used at the top. A note of administrative name is also provided with Carlos’s permission for medical record-keeping and billing purposes. Sex assigned-at-birth does not need to be shared, as it is not relevant to the imaging (e.g., imaging is of the foot, and Carlos cannot be pregnant due to not having a uterus). Carlos is referred to with correct name and pronouns throughout this encounter.

Intake/booking

Intake/booking staff call Carlos to remind him of his follow-up appointment, using his correct name and pronouns, which are prominently visible in the EHR. Data that could reveal his trans status are masked to protect his privacy (e.g., administrative name, sex-assigned at birth).

Referral

Carlos returns to the NP after the blood work and x-ray results have been reported. The NP provides a longer-term prescription for testosterone and schedules regular bloodwork and follow-up appointments. The NP also recommends a referral to an orthopedist due to inconclusive x-ray results. Carlos agrees to the referral, and with his permission, the NP makes the referral using the name and pronouns used by the patient, along with the administrative name for medical record-keeping and billing purposes.

Billing

The billing staff provides Carlos’s health insurance number, administrative name, date of birth, description and date of services rendered, and cost of services to the health insurer. The name and pronouns used by Carlos are masked to protect his privacy.

Research

Administrative staff conduct gender- and sex-based analysis on population data. Carlos’s health experiences and outcomes are included and represented, based on the gender and sex-assigned-at-birth data he voluntarily shared during the registration process. Carlos’s name and other identifying information is not linked to the data available to researchers conducting the analysis, so his privacy is maintained.

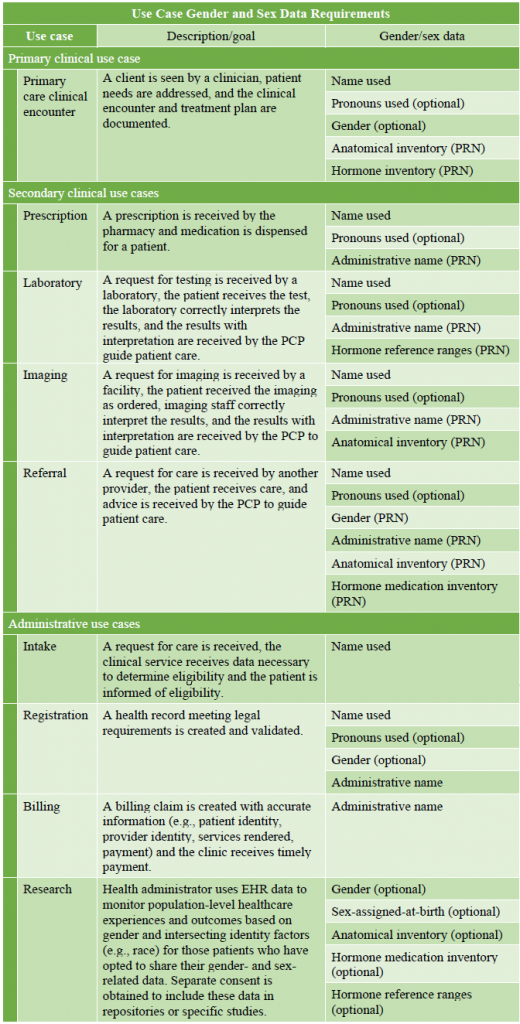

Step 4: Data categories and response options

Through the analysis of the use cases and user story, we formulated eight categories of identification (name, pronouns, administrative name), demographic (gender, sex-assigned-at-birth), and clinical (anatomical inventory, hormone medication inventory, hormone reference ranges) data. Following category development, our team generated response options based on best practices in the literature and the clinical, research, and lived/living expertise of team members (Deutsch et al., 2013; Dunne et al., 2017) (Table 3). For each data category, the purpose of data collection is specified. This collection falls into three main purposes of respectful care, clinical care, and administration (e.g., billing, research). Some data are required (e.g., name used), some are only needed under specific circumstances (e.g., anatomical inventory), and some are desirable for administrative purposes without being required for care (e.g., sex-assigned at birth). Instructions provide additional guidance for implementation (e.g., optional; select all that apply; data collected by clinician, as needed; separate consent for research required). Following user consultation, the categories and response options were revised; final recommendations are found in Table 3.

Table 3. Data categories and response options

Step 5: User consultation

Consultation was conducted with approximately 20 interested parties, including representatives from our Trans Care BC Community Advisory Group (individuals with TTNB lived/living experience), staff team, intersex (i.e., variations of sex development) community, Indigenous health professionals, endocrinology, public health, family medicine, health records, pharmacy, laboratory, and legal. Consultation sessions ranged from one to eight participants, meeting with one to four members of our team. Each session included presentation of the use case and user stories, overview of initial recommendations for gender and sex data collection in EHRs made by the core team, review of data categories and values for each process, and discussion of implications of these recommendations from each interested party’s perspective. Consultation with this broad range of system users elicited feedback that was incorporated into the initial recommendations generated by the core team. This yielded more comprehensive recommendations that were relevant to and representative of the needs of multiple user groups (e.g., patients, health professionals) within British Columbia, Canada.

The following is a summary of the feedback incorporated from consultation sessions. There was broad endorsement of moving away from routine collection of sex-assigned-at-birth as a standard data field and towards anatomical and hormone medication inventories. The term inventories was troubling to community advisors who suggested that the term inventory sounded too cold and material; however, a more acceptable alternate term has yet to be identified. There was support for voluntary collection of sex-assigned-at-birth data by clinicians if relevant to care, or for research purposes with explicit consent. Interested parties requested addition of agender, cisgender, and gender creative to the proposed list of gender options, as well as an option for no pronouns (i.e., name only). They agreed there was need to capture multiple genders and sets of pronouns (e.g., check all that apply). A proposed category of “administrative gender” was removed based on feedback that gender/sex should ideally not be required for health insurance billing, as this creates issues for coverage of “sex-specific” procedures (e.g., cervical screening claim for a patient with a cervix rejected due to a male gender marker). Billing codes would preferably be unrestricted, or alternately, linked to anatomy rather than “sex”. The information captured in the anatomical inventory was determined to serve multiple functions of supporting appropriate screening (e.g., prostate, cervical), differential diagnosis (e.g., presence of ovaries in relation to ovarian cysts), and care planning. It was noted that documentation of tracheal shave and cranio-facial surgeries is relevant for patients in need of intubation and should be captured within a routine medical/surgical history.

Consultation participants expressed that health insurance numbers and dates of birth were useful for identity matching, while names and sex/gender markers were less suitable because they can change and when those data points are relied upon for identity matching this can lead to problematic interactions and barriers to care that disproportionately affect TTNB people. While masking of sex-assigned-at-birth data was largely supported, particularly by TTNB individuals, some interested parties supported retaining this as an identity matching field.

In discussions of privacy, emphasis was placed on the need for patients to update their demographic data (e.g., through a patient portal) and control how their information was shared. The need for patients to know what is in their charts and who will be able to see it was emphasized, and it was suggested that sensitive information (e.g., anatomical inventory, administrative name) be masked to ensure only individuals who require the information are able to access it (e.g., for clinical care, billing). Lastly, interested parties confirmed the need for: clear policy for collection, management, and sharing of gender and sex data; accessible patient information about data policy and privacy; training for all EHR users on data policy and purposes of data collection; and education for all EHR users on trans culturally safer care provision.

Step 6: Recommendations

Our recommendations for data collection within our primary care setting include use of the following categories: name, pronouns, administrative name, gender, sex-assigned-at-birth, anatomical inventory, hormone medical inventory, and hormone reference ranges. The following categories of data should be self-reported and easily updated by the patient: name, pronouns, and gender. The category of Two-Spirit should be available only for people who identify as Indigenous. Provision of data within the following categories should be optional, to respect privacy: pronouns, gender, and sex-assigned-at-birth. For pronouns and gender, patients/clients should be able to select all the response options that apply. Two data categories should be collected or recorded by clinicians and the system should allow clinicians to easily update this information as needed: anatomical inventory and hormone medication inventory. Finally, while we have confirmed with interested parties that the response options are appropriate for our context at this time, they should be regularly reviewed and revised, as necessary.

Through our team discussions and consultation sessions, several recommendations emerged relating to implementation. First, is the need for clear policy and reporting systems concerning the collection, management, and sharing of gender and sex data. Linked to this is the need to limit access to sensitive data within the EHR (i.e., masking) to only those who require the information for their specific duties. Additionally, user interface design should separate gender and name used from administrative name and sex assigned at birth if masking is not feasible. The second area involves providing accessible patient information that explains what information is being collected, why it is being collected, what is required versus optional, how data are protected, and how patients can manage or control their data. Third is the area of staff training. EHR users need to be trained on data categories and response options (e.g., definitions of terms), policy, privacy breach reporting, patient information, and patient communication. In addition to EHR-specific training, staff should also receive education on anti-racism and cultural safety as it pertains to gender and sex data practice.

Discussion

Our six-step process was designed to support the collection of gender and sex data in EHRs in a manner that supports the health and well-being of TTNB people (Callahan et al., 2014; Deutsch et al., 2013; Deutsch & Buchholz, 2015; Dunne et al., 2017; Kutscher, 2016; Samuels et al., 2018). We found this process useful for determining how to design gender and sex data collection within EHRs to meet the needs of a primary care organization, within a specific cultural context. We found the multi-disciplinary team invaluable in pooling expertise and perspectives—in medicine, nursing, counselling, ethics, health care administration, and health informatics. The guiding principles established by the team (e.g., gender-affirming, person-centered, privacy-focused, culturally safe) supported development of data categories and response options that were subsequently largely endorsed by interested parties. The use case and user stories supported a patient-centered care approach and identification of data most appropriate in facilitating optimal care. We recommend ensuring data categories do not serve as proxies, but instead elicit responses that can directly guide clinical care (e.g., avoiding use of sex-assigned-at-birth as a proxy for a person’s anatomical attributes, and replacing this with anatomical and hormone medication inventories). Finally, the consultation process was essential for refining data categories and response options such that they addressed the needs of TTNB communities and the health professionals serving them. Within the consultation process there was also an opportunity to discuss implementation considerations.

Many of our recommendations for data categories aligned with those in the literature. We agree that name used, pronouns, and gender are important for patient-centered, gender-affirming care; however, in contrast to previous publications we do not recommend collecting sex-assigned-at-birth for any purposes other than optional research participation (Deutsch et al., 2013). While this represents an ideal state for clinical care, patient autonomy, and patient privacy, if sex-assigned-at-birth is required for insurance coverage, patients should be made aware of this and give informed consent before this information is shared. We endorse using anatomical inventory and specification of blood test ranges (Deutsch et al., 2013; Kutscher, 2016; Samuels et al., 2018), and additionally recommend hormone medication inventory, to avoid use of sex-assigned-at-birth as a proxy for anatomical and hormone data that can be more accurately collected and updated via these inventories. We support elimination of sex-specific billing codes, as these can lead to erroneous rejection of claims and care can be effectively facilitated through either anatomically-based billing (Deutsch et al., 2013), or complete elimination of such codes.

Response options were initially drawn from the literature, then continually refined based on the input of our team and other interested parties, as relevant within our cultural context (Deutsch et al., 2013; Dunne et al., 2017). In general, we recommend providing response options for the most frequently used categories, ability to select multiple options whenever possible, free text fields to respectfully capture accurate data, options to not respond, and options for unknown data to be collected later. Gender and pronouns should only be identified by the patient, not assigned by another person; therefore, collection may be delayed due to medical presentation (e.g., unconscious) or age (e.g., under age 3). When data are not required, it is important to have a “prefer not to answer” option, so that patients know this is acceptable, do not feel coerced into responding, and are not repeatedly asked for information they do not wish to disclose in future encounters. If information is unknown, this should be indicated and flagged for future data collection.

Similar to other authors, we endorse data collection and management processes that centre patient privacy, through self-report of data, low barriers to updating data, data security, and patient control of data (Callahan et al., 2014; Deutsch et al., 2013; Deutsch & Buchholz, 2015; Dunne et al., 2017; International Institute of Business Analysis, 2015, 2015; Samuels et al., 2018). This use case approach can support identification of which roles truly require access to specific gender and sex data elements and instances where privacy protections can be improved. While the design of EHRs is important to support improved care for TTNB patients, this must be done with appropriate training of staff who interact with patients and utilize these data (Callahan et al., 2014; Dunne et al., 2017; Samuels et al., 2018; Shenoy et al., 2014; Vance & Mesheriakova, 2017). Trans cultural safety policy and training must address the purpose of the data fields, definitions of response options, privacy considerations, and skill-building for supporting respectful, patient-centered, gender-affirming care across settings, including clinical care, pharmacy, laboratory, imaging, billing, and research.

Gender and sex data practices can support nurses and other EHR users in providing care that meets ethical standards. Here we highlight how better gender and sex data practices can support the responsibilities outlined in the Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses (Canadian Nurses Association, 2017). Providing safe, compassionate, competent, and ethical care and honouring dignity are dependent on access to accurate gender and sex information, for example, to facilitate greeting a patient by the correct name and referring to them with the correct pronouns both orally and in documentation. Promoting health and well-being involves recognizing factors leading to health inequities for TTNB patients, such as avoidance of care due to misgendering, which can be supported through EHR-focused TTNB cultural safety training. The design of EHRs can play a critical role in maintaining privacy and confidentiality related to gender and sex, specifically through masking of information that nurses, or other users do not need to know. Designing and implementing EHRs to safeguard the human rights and privacy of TTNB people alongside providing cultural safety training to support nurses and other system users can support ethical practice and reduce EHR-related harms experienced by TTNB individuals.

Significance

We have proposed a novel six-step use case and user story approach to develop ethical and culturally safer sex and gender data practices within EHRs that support equitable, high-quality care within specific cultural contexts. While many findings are consistent with previous publications (e.g., reserving ‘Two-Spirit’ for Indigenous people; separate gender and sex categories, non-binary response options), we recommend against using sex-assigned-at-birth as a proxy data category, instead supporting use of anatomical inventories, hormone medication inventories, and hormone reference ranges to guide clinical care. To promote privacy and patient safety, we emphasize the importance of making disclosure of data optional whenever possible and ensuring patient control of data is supported through policy, as well as patient and staff education. One limitation is that this approach is not intended to yield universal recommendations for gender and sex data practices, which would not make them appropriate to use for internationally universal standards for health information exchange. However, this approach can be used to develop person-centered, gender-affirming, privacy-focused, culturally safer data practices that support appropriate language use and education across health systems within a given context, as illustrated through the primary care use case and user stories within British Columbia, Canada.

Conclusion

Using a primary care setting as an example, we have illustrated how to assemble an appropriate team, identify guiding principles, generate use cases and user stories, draft data categories and response options, conduct consultation with interested parties, and make context-specific recommendations. This use case and user story approach may be applied within diverse care settings and various social, political, and legal contexts to create EHR gender and sex data practices that address the needs of specific organizations and communities. We maintain that privacy is foundational to developing ethical gender and sex data practices and that cultural safety training is essential for effective implementation of EHR changes. Finally, we note that all patients, TTNB and cisgender, as well as nurses and other healthcare providers, can benefit from improved and continually updated gender and sex data practices.

Author Biographies

Drew B. A. Clark, PhD, HEC-C, RCC

Drew is an Assistant Professor in the School of Nursing at The University of British Columbia. They are a certified healthcare ethics consultant and clinical counsellor, with a program for research and teaching that focuses on healthcare ethics and transgender health.

Lindsay MacNeil, MSc

Lindsay holds a Master of Science degree in health informatics. She is a Project Manager and Senior Business Analyst with Trans Care BC, a program of the Provincial Health Services Authority in British Columbia, Canada.

Lorraine Grieves, MA, RCC

Lorraine is the Provincial Program Director of Trans Care BC and has been a leader in TTNB healthcare and administration for over a decade.

Marria Townsend, MD, CCFP

Marria is the Medical Director for Trans Care BC and Clinical Assistant Professor with the Faculty of Medicine, Department of Family Practice, at The University of British Columbia. She is also a practicing family doctor who specialized in TTNB primary care.

Acknowledgments

All authors respectfully acknowledge that our places of work are within the traditional, ancestral and unceded homelands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. Our acknowledgement, gratitude, and respect extend to all Indigenous communities on whose traditional territories our organization builds relationships and provides services. We thank all the interested parties with lived/living and/or professional experience who provided feedback on initial recommendations and paper drafts.

References

Alpert, A. B., Mehringer, J. E., Orta, S. J., Redwood, E., Hernandez, T., Rivers, L., Manzano, C., Ruddick, R., Adams, S., Cerulli, C., Operario, D., & Griggs, J. J. (2022). Experiences of Transgender People Reviewing Their Electronic Health Records, a Qualitative Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07671-6

Bates, N., Chin, M., & Becker, T. (Eds.). (2022). Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26424

Callahan, E. J., Hazarian, S., Yarborough, M., & Sánchez, J. P. (2014). Eliminating LGBTIQQ Health Disparities: The Associated Roles of Electronic Health Records and Institutional Culture. Hastings Center Report, 44, S48–S52. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.371

Canadian Nurses Association. (2017). Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/nursing/regulated-nursing-in-canada/nursing-ethics

Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

Deutsch, M. B., & Buchholz, D. (2015). Electronic Health Records and Transgender Patients—Practical Recommendations for the Collection of Gender Identity Data. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(6), 843–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3148-7

Deutsch, M. B., Green, J., Keatley, J., Mayer, G., Hastings, J., Hall, A. M., & World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group. (2013). Electronic medical records and the transgender patient: Recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA, 20(4), 700–703. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001472

Dunne, M. J., Raynor, L. A., Cottrell, E. K., & Pinnock, W. J. A. (2017). Interviews with Patients and Providers on Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Health Data Collection in the Electronic Health Record. Transgender Health, 2(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0041

Government of Canada, S. of W. C. (2018, December 4). Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+). Status of Women Canada. https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/index-en.html

Grasso, C., Goldhammer, H., Thompson, J., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2021). Optimizing gender-affirming medical care through anatomical inventories, clinical decision support, and population health management in electronic health record systems. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association?: JAMIA, 28(11), 2531–2535. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab080

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. (2011). The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. National Academies Press (US). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64806/

International Institute of Business Analysis. (2015). BABOK: A guide to the business analysis body of knowledge (3rd ed.). International Institute of Buisiness Analysis. https://www.iiba.org/standards-and-resources/glossary/

Kronk, C. A., Everhart, A. R., Ashley, F., Thompson, H. M., Schall, T. E., Goetz, T. G., Hiatt, L., Derrick, Z., Queen, R., Ram, A., Guthman, E. M., Danforth, O. M., Lett, E., Potter, E., Sun, S. D., Marshall, Z., & Karnoski, R. (2022). Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 29(2), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab136

Kutscher, B. (2016). Health systems adapt EHRs, cultures to meet transgender patients’ needs. Modern Healthcare, 46(5), 14–15.

McClure, R. C., Macumber, C. L., Kronk, C., Grasso, C., Horn, R. J., Queen, R., Posnack, S., & Davison, K. (2021). Gender harmony: Improved standards to support affirmative care of gender-marginalized people through inclusive gender and sex representation. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association?: JAMIA, 29(2), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab196

Safer, J. (2019). Hurdles to health care access for transgender individuals. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(11), 1132–1133. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0693-4

Salyer, M. A. (2017). Patients’ Transgender Identity Resulting in Denied Claims. Hospital Access Management, 36(6), 1–3.

Samuels, E. A., Tape, C., Garber, N., Bowman, S., & Choo, E. K. (2018). “Sometimes You Feel Like the Freak Show”: A Qualitative Assessment of Emergency Care Experiences Among Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 71(2), 170-182.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.002

Shenoy, A. M., Kashey, N., Brown, P., & Kudler, N. R. (2014). Better Representing Transgender Patients in the Electronic Health Record. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved; Baltimore, 25(4), 1641–1645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2014.0179

Thompson, H. M. (2016). Patient Perspectives on Gender Identity Data Collection in Electronic Health Records: An Analysis of Disclosure, Privacy, and Access to Care. Transgender Health, 1(1), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0007

Trans Care BC. (2020). Improving gender-affirming care across BC. Provincial Health Services Authority. http://www.phsa.ca/our-services/programs-services/trans-care-bc

Trans Care BC. (2021). Gender-affirming care for trans, Two-Spirit, and gender diverse patients in BC: Primary care toolkit. Provincial Health Services Authority. http://www.phsa.ca/transcarebc/Documents/HealthProf/Primary-Care-Toolkit.pdf

Vance, S. R., & Mesheriakova, V. V. (2017). Documentation of Gender Identity in an Adolescent and Young Adult Clinic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(3), 350–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.018