Attitudes towards Technology in Healthcare among Hybrid Online Nursing Students

by Pinar Ozmizrak, MS, PhD(c)

Luigi Boccuto, MD

Tracy Brock Lowe, RN, MS, PhD

Jane DeLuca, RN, MS, PhD, CPNP-PC

Clemson University School of Nursing, Clemson, SC 29634, USA

Citation: Ozmizrak, P., Boccuto, L., Brock Lowe, T. & DeLuca, J. (2023). Attitudes towards Technology in Healthcare among Hybrid Online Nursing Students. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 18(2). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=11568

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Nursing students use computers for both education and clinical practice. The COVID-19 pandemic changed delivery of education, particularly in nursing which was traditionally delivered through lectures and laboratory sessions. The purpose of this study was to explore students’ perspectives on the use of computers and technology in healthcare education and delivery.

METHODS: A modified version of the Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare (PATCH) assessment scale (Kaminski, 2011) was administered to a US university class of undergraduate nursing students taking a hybrid online and in-person healthcare science course. The PATCH scale gathered students’ ratings of their attitudes towards technology in healthcare using a 5-point Likert scale. Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed in the class of N = 118.

RESULTS: ANOVA revealed no significant difference (p = 0.46) in average ratings of attitudes to technology in healthcare between traditional Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BS) students and 2nd-degree nursing students (already holding another degree). Groups differed significantly (p = 0.03) for the statement “social media tools enrich healthcare professional communication and collaboration,” with BS students agreeing more than 2nd-degree students. The class described positive attitudes towards technology in healthcare with an average rating of 4.16 out of 5. Furthermore, 75.42% of students had an “enthusiastic view” or “idealistic view” of computers in healthcare. These ratings were higher than other comparable studies of nursing students given the PATCH scale.

CONCLUSION: Current nursing students taking hybrid online education strongly support the use of computers and technology in healthcare.

Keywords: nursing, education, informatics, healthcare, technology, PATCH scale.

Background

Technology has become integral to the delivery, instruction, and testing of modern university education. This is through learning management systems (LMS) such as Canvas, BlackBoard, Moodle, or other technologies, which are present at 99% of US higher education institutions (Lang & Pirani, 2014). The use of LMS technology is widespread in at least 77 researched countries (Pham, et al., 2022). With the COVID-19 pandemic affecting the delivery of education to over 1.5 billion students across 188 countries (91.3% of learners worldwide) (Toquero, 2020), emergency remote teaching led to a “digital turn in education,” (Angiolini, et al., 2020, p. 47). Even in disciplines such as nursing where classes were not traditionally offered online, instruction was delivered remotely or in hybrid mode (a combination of online and in-person).

Current undergraduate nursing students are familiar with the incorporation of technology in their education. They are “digital natives”, having grown up with Internet access and social media (Ishak, et al., 2022). Technology is prevalent in students’ education and personal lives. But what of their future careers—how do nursing students feel about the use of technology in the healthcare setting?

Modern healthcare is filled with technology: communicating through online messaging, voice, and video calls (telehealth); data tracking on mobile apps and electronic medical records; and data generation and storage on patient portals. Surveys among healthcare providers show that different professions have varying attitudes and rates of adoption of technology. In a study by Zaslavsky et al. (2022), nurses accepted more health-related technologies than other health professions (psychologists, primary care providers, and others).

In this study, we sought to understand today’s nursing students’ views of technology to improve learner engagement across generational differences. Current nursing students are primarily Gen Z (born 1996 or later) in contrast to today’s nursing faculty, Gen X (born 1965-1980), and this study’s multigenerational, multidisciplinary research team of an online designer, physician, and nursing faculty. Nursing students’ experiences and attitudes reflect a contemporary view of the digital world in healthcare. Soon to graduate, they may have different views from the older nurses they will be working with as colleagues in the clinical area.

The study of generational differences in education has spanned generations itself, to an enduring conclusion paralleled between Mannheim (1952) and Whitehead (2023). Mannheim noted, “generations are in a state of constant interaction,” (1952, p. 180) and expressed that while the teacher educates their student, the student educates their teacher, too. This is reciprocated decades later by Whitehead, who describes 21st-century teachers as lifelong learners who “want their students to be lifelong learners, and they also keep up with the latest developments in education” (2023, p. 51).

Today’s nursing students are in a unique position of having had significantly different experiences to nursing cohorts even just a few years older, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and its impact is still ongoing. Current nursing students have received hybrid online education, in contrast to traditional nursing education in the form of in-person didactic lectures and hands-on laboratory simulations. This study explores the relationship between receiving technology-laden healthcare education and students’ attitudes towards technology in healthcare.

Methods

In 2022, nursing students at a US land-grant university were surveyed using a modified version of the Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare (PATCH) assessment scale (Kaminski, 2011). The PATCH scale is an instrument to reveal perspectives of technology use in healthcare by measuring agreement with given statements, on a 5-point Likert scale of “1 – Strongly Disagree”, “2 – Disagree”, “3 – Not Certain”, “4 – Agree”, and “5 – Strongly Agree.” The PATCH scale has been used among multigenerational nursing students and practicing nurses. The original scale was developed in 1996 and has been updated with newer iterations, the most recent version being published in 2011 to incorporate statements on social media, smartphones, and electronic health records.

The PATCH scale was administered to nursing students taking a healthcare science course. The undergraduate class was composed of traditional Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BS) students and 2nd-degree students (already holding a bachelor’s degree in another discipline). The course had hybrid delivery, where the first few weeks of the semester content was delivered completely online (synchronous lectures on Zoom) and the remainder of the semester delivered in-person. An online LMS (Canvas) and online student assignments were used throughout the course. The PATCH scale was administered at the end of the course. The students were given a modified version of the PATCH scale consisting of 20 statements.

Modification Process

This section describes the modifications that were made to the Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare (PATCH) assessment scale version 3 (Kaminski, 2011).

Statement selection and modification

The PATCH scale version 3 (Kaminski, 2011) has 50 total statements with 25 statements that are positive towards computers in healthcare and 25 statements that are negative. A score towards attitudes to computers in healthcare is calculated by adding the level of agreement with positive statements and the level of disagreement with negative statements, with all statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale of “1 – Strongly Disagree”, “2 – Disagree”, “3 – Not Certain”, “4 – Agree”, and “5 – Strongly Agree.”

The original 50-question PATCH scale (Kaminski, 2011) was modified to 20 questions to shorten the length of time needed to take the survey as well as focus on the statements that would be most relevant to this group of students. As the students were taking the course in hybrid form, they had weeks where instruction had been synchronous online as well as weeks of in-person class. Previously throughout their program, the students had also taken fully online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the students’ experience, several of the general or non-healthcare statements around computer use such as “I feel alarmed when I think of using a computer”, “I don’t intend to own a home computer”, or “people who like computers are introverted and antisocial” were not included in the modified PATCH scale, leading to the selection of statements in Table 1.

In this study, the PATCH scale (Kaminski, 2011) was modified and shortened to a total of 20 selected statements. Statements that were from both the negative and positive sides of the original scale were used; negative statements were reworded to be positive. For example, the original statement “online support groups are a waste of time and have no value for patients” was modified to “online support groups are not a waste of time and have value for patients.” This is so that all statements would be on the same alignment so that students could consistently rate statements with higher agreement indicating support of computers in healthcare.

The modified version of the PATCH scale that was distributed to students is listed in Table 1.

Table 1. The modified version of the PATCH scale distributed to the class, with a total of 20 selected statements

The methods of analysis used included descriptive and inferential statistics. Average, mode, and range were calculated. Statistical significance was evaluated through a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and two-sample assuming unequal variances t-test. The threshold for significance was p < 0.05.

An institutional review board approved the study as exempt human subjects research under 45 CFR § 46.104(d) (Protection of Human Subjects, 2023) with any identifying data removed from the data set. The author of the PATCH scale (Kaminski, 2011) provided permission for its use in a modified form for this research.

Results

Of the 118 nursing students in class, 93 (78.81%) were traditional BS students and 25 (21.19%) were 2nd-degree students. Exact student demographics were not collected to prevent the anonymous survey responses from becoming identifiable.

Statement rating distribution across the class

Table 2 presents the rating data of the class as a whole across the modified PATCH scale and Figure 1 illustrates the rating distribution.

Table 2. Rating distribution data across the 20 statements on the modified PATCH scale

Figure 1. A stacked column chart of statement rating distribution across the class

The percentage of how many students gave each rating on a 5-point Likert scale was depicted across the 20 statements in the modified PATCH scale (Table 2). Due to rounding, the percentage total may not be exactly 100%. Colour grading has been used to show the distribution of ratings, where blue indicates the highest percentage of students giving a particular rating and red indicates the lowest percentage of students giving a particular rating.

General statements about computers’ capacity as a workplace tool (statements 1 and 2) demonstrated high consensus among the class ratings, with statement 1, “the computer is a powerful enabling tool,” receiving 100% agreement. For each statement, a majority of students (>50%) rated their agreement (“5 – Strongly Agree” or “4 – Agree”) with the exception of statement 4. Across the entirety of the modified PATCH scale, the class average rating was 4.16 (Table 3), indicating agreement.

The statement receiving the highest proportion of disagreement was statement 14, “I use healthcare apps on my cellphone or SMART phone,” with 24.57% of the class rating “2- Disagree” or “1 – Strongly Disagree.” However, with an average rating of 3.75, this was not the lowest-rated statement on the scale. Still 67.80% of students agreed or strongly agreed with using healthcare apps, marking this as the most divisive statement on the modified scale.

The class was in 99.15% agreement with statement 2 that “in healthcare, computers could save a lot of paperwork”, but they ranked computers’ role in lessening their workload less favourably. Statement 7, “computers in healthcare will not create more work for nurses to have to do,” had the second-lowest average rating of the scale at 3.56. The lowest average rating was 3.33 for statement 4, “bedside computers will not irritate patients.” This also elicited the highest uncertainty across the statements, with 39.83% of the class rating their opinion as “3 – Not Certain.”

BS students versus 2nd-degree students

Table 3 presents the average rating data of the BS students compared to the 2nd-degree students and Figure 2 illustrates the average rating distribution across the two groups.

Table 3. Average rating data of statements on a scale from 1 to 5

Table 3 presents the average rating data of the BS students, 2nd-degree students, and class as a whole across each of the 20 statements on the modified PATCH scale. The bottom row shows the average across all 20 questions for each group. Colour grading has been used to show the distribution of ratings, where red indicates the lowest average rating and blue indicates the highest average rating.

Figure 2. A clustered column chart of the average statement rating for BS versus 2nd-degree students, with statistically significant differences indicated by an asterisk

The BS students had higher average ratings than the 2nd-degree students for 13 out of the 20 modified PATCH statements and higher overall average ratings of 4.18 vs. 4.08 respectively. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed on the average statement rating data between the BS and 2nd-degree students across the PATCH scale determined a p-value of 0.46. With a p > 0.05, the results reveal there is not a statistically significant difference between the two groups in their average agreement of statements across the PATCH scale supporting technology in healthcare.

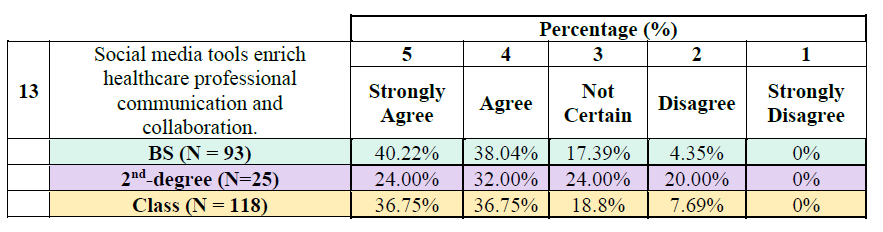

The differences in ratings between BS and 2nd-degree students were next analyzed for each statement. After performing a two-sample assuming unequal variances t-test for each of the 20 statements, statement 13 “social media tools enrich healthcare professional communication and collaboration,” was identified to have a significant difference between the two groups (p two-tail = 0.03 < 0.05), as shown in Table 4 and Figure 3. The other statements did not have a statistically significant difference (p two-tail > 0.05).

Table 4. Statistically significant different rating distribution for statement 13

Figure 3. A clustered column chart of the statement 13 rating distribution for BS versus 2nd-degree students

Table 4 and Figure 3 depict the rating distribution for statement 13, specifically due to its statistical significance. Due to rounding, the percentage total may not be exactly 100%. Colour grading has been used to show the distribution of ratings, where blue indicates the highest percentage of students giving a particular rating and red indicates the lowest percentage of students giving a particular rating.

Statement 13, “social media tools enrich healthcare professional communication and collaboration,” had the largest difference in rating between the two groups of students, as seen in Figure 3. BS students rated it 4.14 on average, while 2nd-degree students rated it 3.60. This was the only statistically significant difference among the 20 statements assessed (p two-tail = 0.03).

PATCH level outcomes

The ratings of each statement of the modified PATCH scale were tallied to an overall score. For direct comparison purposes across other studies, the scores of the modified PATCH scale were converted to the scoring of the original PATCH scale version 3. The conversion process is described below.

The students were assessed as one of the following six levels on the original PATCH scale, illustrated in Figure 4.

Modified scoring and scale conversion

The original 50-question PATCH scale (Kaminski, 2011) uses a 5-point scale from 0 to 2 for scoring with a range of 0 to 100 points. Our modified 20-question version used a 5-point scale from 1 to 5 with a range of 20 to 100 points.

Because of the linear relationship between the two scales, the following formula was used to convert a score from our modified PATCH scale (x) to the original scale (y), for assessment along the level system.

y = 1.25 * (x – 20)

For example, for a student whose 1-5 ratings of the 20 questions on the modified PATCH scale sum to 72, their score on the original scale would correspond to 65, which places them at level 4 for the assessment.

Figure 4. PATCH scale outcome levels

Table 5 shows the overall scores of the class on the original PATCH scale, which are illustrated by group in Figure 5.

Table 5. PATCH scale rating outcomes and level scores

Table 5 depicts the PATCH scale score distribution count, distribution percentage, average score, and average level for the BS students, 2nd-degree students, and the whole class. Due to rounding, the percentage total may not be exactly 100%. The scores of the PATCH scale correspond to six levels, with level 1 indicating the least support of technology in healthcare and level 6 indicating the highest support of technology in healthcare.

Figure 5. A clustered column chart of distribution of the outcome levels among the class

Figure 5 depicts the percentage of BS students, 2nd-degree students, and class as a whole that scored at each level of the PATCH scale, where a lower level indicates lower support for technology in healthcare, and a higher level indicates higher support.

Discussion

A modified version of the PATCH tool was administered in a hybrid class setting to explore nursing students’ perspectives of computers and technology in education and healthcare delivery.

BS students versus 2nd-degree students

The scores from the PATCH scale of attitudes toward computers and technology in healthcare were uniformly similar between the two groups, traditional BS nursing students and 2nd-degree nursing students.

Both groups rated computers as powerful devices that would save paperwork but did not necessarily agree that it could create less work for them; rather they were uncertain. A switch from paper medical records to electronic health records has been shown to decrease administrative work for nurses but increase time spent on documentation (Banner & Olney, 2009). Though saving paperwork, computers create screen time.

Nurses have reported concerns about computer fatigue and screen work taking time away from patient care at the bedside (Gregory, et al., 2022). This is reflected in the students’ ratings. Despite unanimous agreement about the powerful capability of computers, students were discerning in their reception of computers in the patient experience. Statement 4 “bedside computers will not irritate patients” elicited the most uncertainty, representing 39.83% of the class (this statement also had the lowest average rating of the survey at 3.33).

Statement 14, “I use healthcare apps on my cellphone or SMART phone” received the strongest disagreement among students for a combined proportion of 24.57%, however, this was not the lowest rating of the class. Roughly 67.80% of students also agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, making it the most polarizing statement surveyed. This divide appears reasonable since students either do or do not make use of healthcare apps. Though 7.63% of students responded as not certain, this could mean they were perhaps unsure of what constituted a healthcare app.

The only statistically significant difference between groups for the 20 statements assessed (p two-tail = 0.03) was Statement 13, “social media tools enrich healthcare professional communication and collaboration.” This may be attributed to generational differences between the two student groups. The BS students were predominantly Gen Z and younger than the 2nd-degree students. Gen Z students have been shown to have the most multipurpose use (education, entertainment, shopping, socialization, and information seeking) of social media compared to older generations (Mude & Undale, 2023). They are described as “socially and community minded” (Hampton & Welsh, 2019, p. 483), which might contribute to the BS students’ preference for using social media.

With no other statements showing a statistically significant difference, a difference in age or previous educational experience (with 2nd-degree students being older and having a prior university degree) did not have an impact on the ratings.

Students showed an overall agreement with statements supporting technology in healthcare with an average rating of 4.16 out of 5 across the PATCH scale. However, there was still a varied distribution among responses with 18 out of the 20 statements receiving at least four different ratings on the 5-point Likert scale. While the BS students had higher average ratings than the 2nd-degree students for 13 out of the 20 statements, both groups agreed with statements supporting technology in healthcare with no statistically significant difference between the two in their average agreement of statements across the modified PATCH scale.

Figure 5 demonstrates that on average, BS students had higher scores and higher support of technology in healthcare, although ANOVA revealed it was not a significant difference. All but one student scored level 4 or higher, indicating comfort with computers and an awareness of their use in healthcare. The single student scoring level 3 was from the BS group. The mode for both BS students and 2nd-degree students was level 5, accounting for 46.24% and 40.00% of each group, respectively. After level 5, the second most common group for BS students was level 6, and for 2nd-degree students was level 4.

The average level of the class was 5.05. A score of level 5 surpasses the comfort of lower levels to indicate confidence in using computers and an enthusiastic view of their potential in healthcare, but without the idealistic view of level 6.

Comparison with other studies using the PATCH scale

The PATCH scale has been implemented in several other studies spanning a number of years, versions, countries, and populations, from nursing students to practicing nurses. There are at least three other studies that have researched the PATCH scale (version 3) in undergraduate nursing or midwifery students. Because of the version and student population, these studies are comparable to this current study of a US undergraduate nursing class. These previous studies take place in universities in Saudi Arabia (Alaban, et al., 2020), Turkey (Atay, et al., 2014), and India (Vijayalakshmi, et al., 2014).

In this study, 30.51% of the class scored level 6, which is the highest level of the PATCH scale and indicates confidence in using computers for creative and routine functions and an idealistic perspective of their use in healthcare (Figure 4) (Kaminski, 2011). Comparatively, 7.30% of students scored level 6 in Saudi Arabia, 7.70% of students in Turkey, and 0% of students in India. This indicates that this study’s group of students had the highest scores of the top level of the PATCH scale, both globally (across countries) and historically (across years) among other nursing students.

When looking at the lower end of the PATCH scale, only 0.85% of the current class (1 student) scored level 3 or lower. Comparatively, 15.30% of students scored level 3 or lower in Saudi Arabia, 5.30% of students in Turkey, and 10.50% of students in India. Globally and historically, this study had the fewest nursing students scoring in the bottom half of the PATCH scale.

The most common score (mode) was level 5, representing 44.92% of students in this study. Comparatively, the mode was level 4 representing 47.30% of students in Saudia Arabia, the mode was level 5 representing 45.30% of students in Turkey, and the mode was level 4 representing 77.00% of students in India. Thus, the mode of level 5 in this study was as high as has been globally and historically reported among nursing students, but not higher.

The majority of this study’s class scored in the top levels, with 75.43% scoring level 5 or 6. Comparatively, 77.30% of students scored level 4 or 5 in Saudia Arabia, 87.00% scored level 4 or 5 in Turkey, and 89.40% scored level 4 or 5 in India. This shows that although globally and historically most nursing students have scored in the top half of the PATCH scale, this study has the highest distribution of students at the top end of the scale.

Combining these results shows that globally and historically among studies using the PATCH scale to assess nursing students, this study had the fewest proportion of students scoring in the lower half of the PATCH scale and the highest proportion of students scoring in the top level of the PATCH scale.

Across studies, factors affecting these resultant scores may originate in both the year and setting of administering the tool and obtaining the PATCH results. This research was the first post-COVID-19 study using the PATCH scale. This is the only course we are aware of to have an online component examined. In addition, although all studies used version 3 of the scale, it was last updated in 2011 to incorporate perspectives on social media and smartphones. In the decade since, these concepts have become more ubiquitous. Also, students in the previous studies may have had limited access to and training with computers. While the computer access history of this class of students was not assessed, the cohort’s first academic year of the nursing program aligned with the transition to emergency remote education due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, up to this point in 2022, the students had experienced more of the program online than they had in-person, assuring that this cohort had unprecedented computer access and expertise in online classes. Most likely, for the BS students, this would have been their first and whole experience of university education, while the 2nd degree students would have received their prior degree in a traditional in-person university setting.

These results are comparisons of the modified (i.e., shortened PATCH) compared to the full version 3 of the PATCH scale. However, the statements excluded from the modified version were those around general computer use where students would be expected to score highly in support of technology based on their hybrid online student experience (such as “I regularly use a computer at home”). Even with these likely high-support statements removed, the class as a whole scored highly on the PATCH scale and higher compared to other studies.

Conclusions and future research

The results of this administration of the modified PATCH scale show higher scores and higher support for technology in healthcare than any other reported study of the PATCH scale (Kaminski, 2011) in nursing students. As a limitation, the results of this study might not be generalizable to other situations and a singular cause for the high-scoring results cannot be determined. Rather, there are multiple possible contributing factors such as that this is the most recent study and performed in a US university.

Time period and location affect all studies, but a notable difference of this group was that it was the first administration of the PATCH scale (Kaminski, 2011) after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This, along with the students’ own lived experience of receiving technology-based hybrid online nursing education, could have affected students’ perspectives of the power of technology in healthcare and resulted in the strong outcomes reported in this study.

Follow-up to this work can be to evaluate if a higher affinity shown by students for technology translates into higher grades in hybrid or online courses. With this study demonstrating that nursing students show support for technology in healthcare, future research can investigate if modernizing educational delivery through interactive digital coursework similarly achieves improvements in student engagement and productivity.

With the global effect of COVID-19 and its impact on healthcare as well as education, future studies implementing the PATCH scale in international post-COVID classrooms will be valuable to further study the influence of receiving online nursing education on perspectives towards technology in healthcare.

Overall, the results of the modified PATCH scale show that this class of nursing students at a US university whose generation has had lifelong experience with computers and who have partaken in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic have a highly positive view on the use of computers in their future healthcare careers.

Author Information

Pinar Ozmizrak, MS, PhD(c) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2689-5346

Luigi Boccuto, MD https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2017-4270

Tracy Brock Lowe, RN, MS, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1115-1405

Jane DeLuca, RN, MS, PhD, CPNP-PC https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0600-9500

References

Alaban, A., Almakhaytah, S., Almayouf, L., Alduraib, A., Althuyni, A., & Bin Meshaileh, L. (2020). Assessment of Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Attitudes and Perceptions towards the Use of Computer Technology in Healthcare Settings. Iris Journal of Nursing and Care, 3(3), e1-3. doi:10.33552/IJNC.2020.03.000561

Angiolini, C., Ducato, R., Giannopoulou, A., & Schneider, G. (2020). Remote Teaching During the Emergency and Beyond: Four Open Privacy and Data Protection Issues of ‘Platformised’ Education. Opinio Juris in Comparatione, Studies in Comparative and National Law, 1(1), 46-72. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3779238

Atay, S., Arikan, D., Yilmaz, F., Aslanturk, N., & Uzun, A. (2014). Nursing and midwifery students’ attitudes to computer use in healthcare. Nursing Practice Today, Quarterly, 1(3), 147-154. https://npt.tums.ac.ir/index.php/npt/article/view/22

Banner, L., & Olney, C. M. (2009). Automated clinical documentation: does it allow nurses more time for patient care? CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 27(2), 75-81. doi:10.1097/NCN.0b013e318197287d

Gregory, L. R., Lim, R., MacCullagh, L., Riley, T., Tuqiri, K., Heiler, J., & Peters, K. (2022). Intensive care nurses’ experiences with the new electronic medication administration record. Nursing Open, 9(3), 1895–1901. doi:10.1002/nop2.939

Hampton, D., & Welsh, D. (2019). Work values of generation Z nurses. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(10), 480-486. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000791

Ishak, N. M., Ranganathan, H., & Harikrishnan, K. (2022). Learning Preferences of Generation Z Undergraduates at the University of Cyberjaya. Journal of Learning for Development, 9(2), 331-339. doi:10.56059/jl4d.v9i2.584

Kaminski, J. (2011). P.A.T.C.H. Assessment Scale v. 3. https://nursing-informatics.com/niassess/plan.html

Lang, L., & Pirani, J. A. (2014). The Learning Management System Evolution. CDS Spotlight Report. Research Bulletin. EDUCAUSE. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2014/5/the-learning-management-system-evolution

Mannheim, K. (1952). The sociological problem of generations. Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, 306, 163-195.

Mude, G., & Undale, S. (2023). Social Media Usage: A Comparison Between Generation Y and Generation Z in India. International Journal of E-Business Research (IJEBR), 19(1), 1-20. doi:10.4018/IJEBR.317889

Pham, P., Lien, D., Kien, H., Chi, N., Tinh, P., Do, T., Nguyen, L. & Nguyen, T. (2022). Learning Management System in Developing Countries: A Bibliometric Analysis between 2005 and 2020. European Journal of Educational Research, 11(3), 1363-1377. doi:10.12973/eu-jer.11.3.1363

Protection of Human Subjects. (2023). Subpart A—Basic HHS Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects. 45 CFR § 46.104(d). The Office of the Federal Register. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-A/subchapter-A/part-46/subpart-A#p-46.104(d)

Toquero, C. M. (2020). Challenges and opportunities for higher education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The Philippine context. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), em0063. doi:10.29333/pr/7947

Vijayalakshmi, P., Ramachandra, S., & Math, S. (2014). Nursing students’ attitudes towards computers in health care: a comparative analysis. Journal of Health Informatics, 6(2), 46-52. Retrieved from https://jhi.sbis.org.br/index.php/jhi-sbis/article/view/286

Whitehead, E. (2023). Augmented Skills of Educators Teaching Generation Z. Excellence in Education Journal, 12(1), 32-54.

Zaslavsky, O., Chu, F., & Renn, B. N. (2022). Patient Digital Health Technologies to Support Primary Care Across Clinical Contexts: Survey of Primary Care Providers, Behavioral Health Consultants, and Nurses. JMIR Formative Research, 6(2), e32664. doi:10.2196/32664