Evaluation of Smart Pill Bottle Systems on Medication Compliance: An Integrative Review

by Enrico Del Rosario

Kristine Bayoran

Joyce Demdam

Leocel Gallenero

Daniel Valdez

Roison Andro Narvaez

St. Paul University Philippines – Graduate School

Citation: Del Rosario, E., Bayoran, K., Demdam, J., Gallenero, L., Valdez, D. & Narvaez, R. (2023). Evaluation of Smart Pill Bottle Systems on Medication Compliance: An Integrative Review. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 18(3). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=12215

Abstract

Background: Smart pill bottle systems (SPBs) were designed to support patients in medication compliance. Poor medication compliance can result in decreased quality of life, poor disease prognosis, increased health care costs, and increased death rate.

Aim: To provide a comprehensive review and evaluate existing data related to the utilization of smart pill bottle systems to medication compliance.

Methods: An integrative review

Results: Seven articles satisfied the eligibility criteria on the use of SPBs to monitor their medication adherence. Physical features were identified as a barrier to patient’s preference to SPBs. SPBs were found to have high medication adherence among patients with different conditions and also found to improve patient’s well-being.

Conclusion: Patients who used SPBs were satisfied with their function, SPBs paired with other technologies improved medication adherence and had a positive impact on users’ conditions.

Implication for practice: SPBs show a positive impact on medication adherence that should be taken into consideration to study SPBs in a wider context and integrate with other interventions that contribute to overall impact of the users well-being.

Keywords: Smart Pill Bottle System, Medication Adherence, Acceptability, Clinical routine, Integrative Review

Background

Medication compliance is a major challenge in healthcare and can have a major impact on an individual’s well-being. Medication compliance is a less favoured terminology by many nowadays as it could be regarded as passive patient behavior to medication use. It means patients follow appropriate medication regimens as prescribed by their primary care provider. This includes compliance to frequency, timing, and dosage (Cramer et al., 2008). Medication compliance and medication adherence are often used synonymously. However, the two terms have varied definitions. As defined by the National Stroke Association, medication adherence is an act of promptly filling new prescriptions or refilling existing ones (Ross, 2022).

Once a patient is discharged home from a healthcare facility, no one will monitor their medication compliance. In the United States, poor compliance has been linked to a lower quality of life, the progression of disease, higher mortality rates, and increased expenses associated with medical care. Poor medication adherence causes 125,000 deaths and $100 billion in healthcare costs annually. According to reports from the World Health Organization, the percentage of patients who stick to their pharmaceutical regimens for treating chronic illnesses is approximately 50% (Bentley & Potts, 2021). Poor medication compliance occurs for many reasons. Patient factors, physician-related factors, and healthcare system factors were identified as major contributors to medication non-compliance (Brown & Bussell, 2011). Technological advancements in healthcare aids in decreasing medication non-compliance through the use of smart pill devices (Pal et al., 2021).

Smart pill bottles detect if patients have taken their prescription automatically. Wireless transmission of data from the bottles to AdhereTech servers allow for real-time analysis (Grant & Steele, 2016). More advanced smart pill bottle systems have also been added to be cost-effective and easy to use technology with the aid of smartphones. Most smart pill bottles provide accurate results and statistics to monitor medication compliance (Kataria et al., 2021). With the rapid advancement of the Internet of Things (IoT), medication adherence data is now instantly retrievable (Faisal et al., 2021).

Park et al., (2022) revealed that the use of SPBs as a reminder for medications scheduling was significant in boosting medication compliance and self-efficacy. Moreover, a systematic review on the use of mobile technology to improve medication compliance showed an overall improved satisfaction and feasibility of usage of mobile pill bottle systems in reducing mood symptoms (Rootes-Murdy et al., 2018).

The aim of this paper is to review and evaluate existing data related to the utilization of smart pill bottle systems on medication compliance and also analyze the usability of this technology. This narrative review looks at patient preference of these products, their impact on adherence and use in routine clinical care.

Methods

Design

The framework of Whittemore and Knafl (2005) was used to acquire new understanding by thoroughly analyzing and synthesizing various perspectives on the subject. The framework consists of defining the issue, doing a literature search, analyzing and assessing the evidence, and synthesizing the conclusion. This study includes experimental and non-experimental designs in the search which provides empirical evidence to investigate certain phenomena (Souza et al., 2010).

Search strategy

A search was initiated using the following electronic resources: ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Google Scholar. Keywords utilizing the Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) such as: Smart Pill Bottle Systems, Electronic Pill Bottle, Medication Compliance were used.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search was limited to full text English published journals as recommended by Whitemore and Knalf (2005). Additionally, marketed or prototype SPBs were also included in the review. Wearable smart devices and other Smart devices that measured medication adherence, reviews, abstracts, and non-English published journals were excluded in the search strategy.

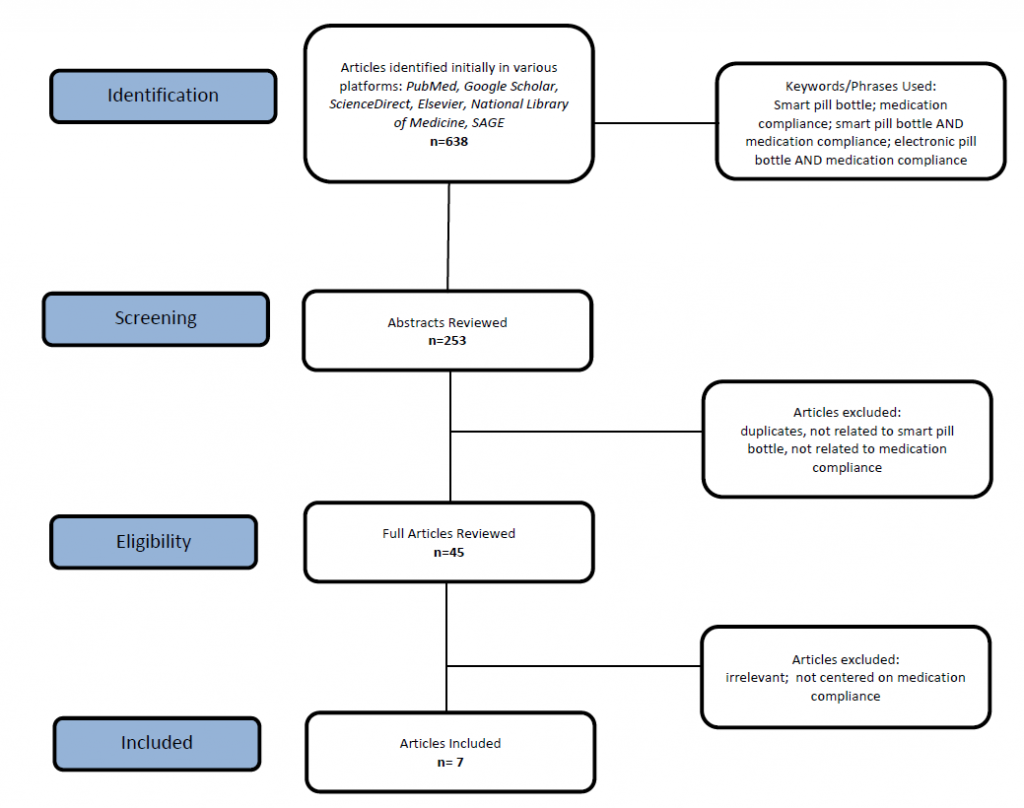

A bibliographic reference manager was used to organize the literature search. The search generated 638 journals. Duplicated journals were excluded, reducing the number to 268. Review articles and abstracts were then excluded generating 253 articles. 253 journals were then reviewed, and 208 journals were excluded due to unmet criteria of this study. This left 45 articles to assess. The reason for this is that these articles were irrelevant and were excluded in the search strategy. There were 38 articles identified but only seven articles satisfied the inclusion criteria of this review. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria, (Moher et al., 2009) a flowchart depicting the selection of studies is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Search strategy and selection of papers related to use of smart pill bottle systems on patient’s medication compliance.

Data Evaluation and Quality Assessment

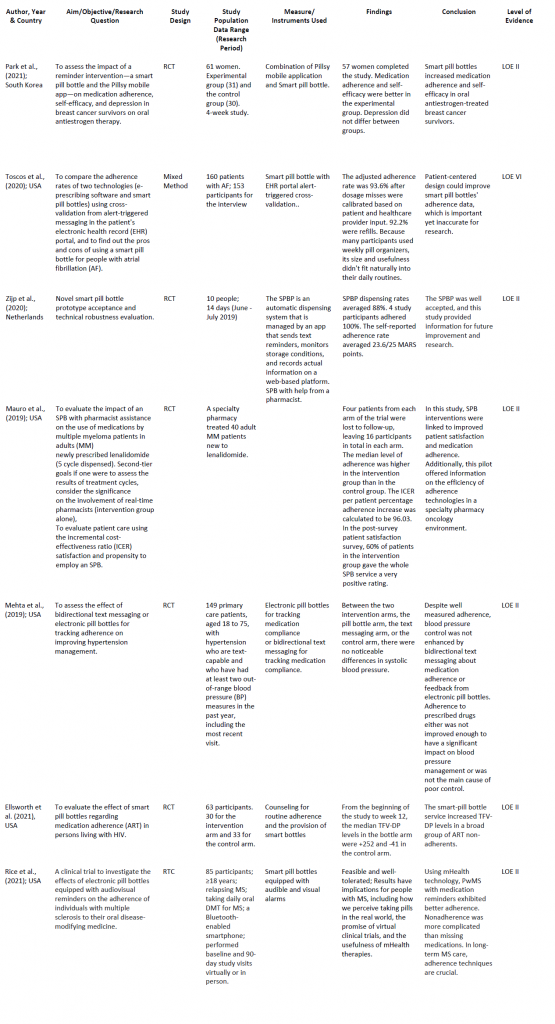

A comprehensive/matrix table was used to classify the data that had been extracted from the databases using the Sparbel & Anderson (2000) tool with the following information: author, year of publication, design, method, sample size and participants, sampling technique, aim, and the study’s findings (Table 1).

Table 1

Characteristics

The assessment of methodological quality of this integrative review was independently done by the researchers. A two-stage screening procedure was used to increase accuracy and reduce bias. Two researchers independently selected publications for the integrative review, and any discrepancies were settled by a third researcher. After the initial review, all 45 included papers were provided to the authorship group for assessment along with the inclusion and exclusion criteria after the initial review. All articles had to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All articles were published in English, comprehendible, and published in no specific geographical region between January 2017 and September 2022. Additionally, to assess the quality of each article further, articles were evaluated based on their level of evidence as suggested by the Melnyk Model. Furthermore, the rating system, Hierarchy of Evidence for Intervention and Treatment Question, was used to classify each article based on their Level of Evidence (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2015). In addition, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2019) was also used to assess the rigour of each journal.

Data Analysis / Quality Appraisal

Following agreement on the screening procedure, each authorship team member discussed their case for adding or omitting papers in the study. Each article’s information was then inputted in an Excel sheet for review by the group. Four meetings were held to further specify the articles to include or exclude. The discussion surrounding this procedure was by consensus. This reference checking procedure resulted in the exclusion of 38 papers from the study as these articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Additionally, to assess further the quality of each article, articles were assigned based on their level of evidence as suggested by the Melnyk Model. Furthermore, the rating system, Hierarchy of Evidence for Intervention and Treatment Question, was used to classify each article based on their Level of Evidence (Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, 2015).

Results

The timeline coverage of the final selected studies was from 2019 to 2022. Five studies were from the United States of America (Ellsworth et al., 2021; Mauro et al., 2019; Mehta et al., 2019; Rice et al., 2021; Toscos et al., 2020); one from South Korea (Park et al., 2022); and one from Netherlands (Zijp et al., 2020). Seven studies reported using quantitative methods with randomized controlled trials as the most utilized (Choi, 2019; Ellsworth et al., 2021; Mauro et al., 2019; Mehta et al., 2019; Park et al., 2022; Rice et al., 2021). One study utilized a mixed-method design: randomized clinical trials with a structured interview (Toscos et al., 2020). Six studies were classified as having levels of evidence of II and 1, and one study was classified as level VI. The total sample size for all papers analyzed was 586 respondents.

In monitoring adherence, Park et al. (2022) paired SPBs with a Pillsy Mobile app, Toscos et al. (2020) utilized patient EHR portal alert-triggered messaging, Mauro et al. (2019) utilized pharmacist intervention with SPBs; Ellsworth et al. (2021) used the smart-bottle service and patients were given instructions on how to work it, audio visual reminders with SPB were used by Rice et al. (2021), and Zijp et al. (2020) tested the SPBP as an automatic dispensing system and captured real-time data on a web-based platform. Data were categorized as Acceptability of SPBs, Impact on Medication Adherence, and the use of SPBs in routine clinical care.

Acceptability of SPBs

The acceptability of SPBs were reported in five studies (Ellsworth et al., 2021; Park et al., 2022; Rice et al., 2021; Toscos et al., 2020; Zijp et al., 2020). Participants claimed that they preferred a handy SPBs (Park et al., 2022) and patients provided negative feedback such as feeling like they were frustrating, annoying, or nagging, but the acceptance of SPBs was highly effective (Rice et al., 2021). Smart Pill Bottles services gained satisfactory acceptance results, as easy to use (Zijp et al., 2020), and simple to use (Toscos et al., 2020).

Impact on Medication Adherence

SPBs as a main instrument to measure medication adherence were found to have a significant impact on patients who had different types of condition. One study showed that using a smart pill bottle and a Pillsy application as a reminder can increase medication self-efficacy and adherence in breast cancer survivors taking anti hormonal drugs (Park et al., 2022). Another concluded that there was high medication adherence among uncontrolled hypertensive patients but there was no improvement in controlling their blood pressure (Mehta et al., 2019). Patients with Multiple Sclerosis received medication adherence audiovisual reminders on oral disease modifying therapy (DMT) with greater adherence rates than the ideal (Rice et al., 2021). Patients under a controlled group with pharmacist intervention resulted with a high medication adherence rate (Mauro et al., 2019). Patients with HIV on antiretroviral treatment who were chosen at random reported to have high medication adherence and to have higher Tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) levels by dried blood spot (Ellsworth et al., 2021). Patients with atrial fibrillation also used smart pill bottle software with quite high adherence rates which was higher than most patients with chronic diseases (Toscos et al., 2020).

SPBS in routine clinical care

Reminder interventions using an app and a smart pill bottle could help breast cancer survivors receiving adjuvant oral estrogen therapy increase their short-term medication adherence and self-efficacy (Park et al., 2022). SPBs provided positive patient visit outcomes in one study, concentrated on the reliable measurement of blood pressure control, which was a significant clinical result, during a clinic visit (Mehta et al., 2019). A SPBS was linked to a significant increase in antiretroviral medication levels in a varied sample of HIV-positive individuals who had shown unsatisfactory adherence to their antiretroviral regimen, which could be predicted to enhance virologic suppression rates over time (Ellsworth et al., 2021). The result of the study by Toscos et al. (2020) showed a significant outcome since it underlined the necessity for a feedback loop between patients and physicians on medication adherence and the possibility for the EHR and patient portals to serve as sources of validation for information obtained via distant technology. A SPB prototype that included design and implementation considerations for a pill bottle connected to a mobile phone was tested, and provided information involving patients in their dose schedule and sending reminders (Zijp et al., 2020).

Discussion

In this integrative review, the authors aimed to synthesize findings based on the published literature which reported the use of pill bottles to improve medication adherence among patients. This review addressed gaps which previous researchers failed to report. Three themes emerged during this review: Acceptability of SPBS, Impact on Medication Adherence, and SPBS in routine clinical care.

Acceptability of SPBS

Acceptability of SPBs was identified as one of the key themes in this integrative review. Five studies examined the satisfaction and acceptability among the end users of SPBs. Among the five studies, three studies utilized a satisfaction and acceptability survey (Ellsworth et al., 2021; Park et al., 2022; Zijp et al., 2020) and two studies included their findings based on their thematic analysis (Rice et al., 2021; Toscos et al., 2020). The results of this review showed that participants who were involved in various studies rated the intervention as highly satisfactory and highly acceptable in terms of its usability (Ellsworth et al., 2021; Park et al., 2022; Zijp et al., 2020). Additionally, two studies reported based on participants’ responses that the physical features such as the size and bulkiness of the bottle affected their preference (Toscos et al., 2020), while some participants expressed that they found the bottle a bit frustrating and nagging because of its physical features, but the use of SPBs was effective (Rice et al., 2021). This suggests that thr physical features of SPBs considerably affect the preference of the end-users and the usability and effectiveness of SPBs. Moreover, Rice et al., (2021) reported that participants who were involved in the study were not certain if the Bluetooth device was syncing properly when monitoring adherence when they went outside of their residence. Park et al., (2022) suggested that SPBs should be smaller and handier so that participants could carry these devices anywhere they wanted.

The results of this review pointed out how the SPBs were viewed by the participants as acceptable for usability and functionality. The utilization of SPBs were highly acceptable as the function of these devices support patients to adhere to their medication regimen. End-users of SPBs reported that they were highly acceptable, users were satisfied, and their functions were found to be effective (Ellsworth et al., 2021; Park et al., 2022; Zijp et al., 2020); however, physical features were negatively reported to affect patients’ preference of SPBs, but they were still found to be effective (Rice et al., 2021; Toscos et al., 2020).

Impact on Medication Adherence

The studies that were reviewed mainly investigated medication adherence rates when using commercially available SPBs among patients with different diagnoses (Ellsworth et al., 2021; Mauro et al., 2019; Mehta et al., 2019; Park et al., 2022; Rice et al., 2021; Toscos et al., 2020) and one study reported a novel SPB prototype to measure medication adherence (Zijp et al., 2020). The use of SPBs significantly improved the medication adherence among patients in these studies. The highlight of this review is that when SPBs were paired with other interventions such as the Pillsy Mobile Application (Park et al., 2022), monitored alert-triggered messaging within the patient electronic health record (Toscos et al., 2020), pharmacist intervention (Mauro et al., 2019), audio visual reminders (Rice et al., 2021); or SPBP as an automatic dispensing system that captured real-time data on a web-based platform (Zijp et al., 2020) considerably improved medication adherence was evident. However, Mehta et al., (2019) and Park et al., (2022) revealed that, though the use of SPBs improved medication adherence rates, there was no evidence that SPBs improved systolic blood pressure among hypertensive patients or improved depressive symptoms of breast cancer patients respectively. This is mainly because SPBs were designed to monitor adherence to medication. This gap in the utilization of SPBs can be addressed by integrating other interventions such as psychological support (Park et al., 2022), as this would monitor the overall outcome of a patient’s medical condition.

The results were similar when medication adherence was measured. As previous literature reported on high medication adherence when SPBs were integrated, this review similarly reported high medication adherence combined with several interventions to support medication adherence. This review assessed several studies and reported a positive impact on a patient’s medication adherence; but some studies utilized a short period of time for their clinical trials and this raised questions as to whether this period would provide accurate results on medication adherence in the long run. Consequently, the combination of other interventions with the utilization of SPBs provided the most promising result in the improvement of medication adherence by patients.

SPBs in routine clinical care

The use of SPBs in measuring adherence rate was high based on the previous review, however, only one study demonstrated that this device-based approach shows significant improvement in adherence (Ellsworth et al., 2021; Mehta et al., 2019; Park et al., 2022; Toscos et al., 2020). A smart-pill bottle service was linked to a large rise in antiretroviral drug levels, which was predicted to lead to a gradual improvement in virologic suppression rates (Ellsworth et al., 2021). The findings of Park et al., (2022) provided evidence in favour of the effectiveness of smart pill bottle reminder interventions for breast cancer survivors receiving adjuvant oral estrogen medication. This intervention may be particularly beneficial for women who struggle to remember to take their medications on a regular basis. Mehta et al., (2019) revealed that adjusting antihypertensive drugs for vulnerable races can affect the optimal results in monitoring blood pressure, and provided evidence that SPBs can increase adherence rates. Toscos et al., (2020) reported some disparities including changes to regular medication schedules and design flaws could affect medication adherence behaviour. The results of this review showed a promising and considerable improvement on medication adherence among various types of patients.

SPBs seem to be significant in improving medication adherence which can provide positive results to patient overall condition. This review showed improvement of some patients’ conditions, however, some studies reported discrepancies on the utilization of SPBs among diverse types of participants. Factors such as intensification of medications, participants’ race, the frequency of visits to their primary care provider, severity of patient’s condition could affect the compliance of patients.

Limitations and Recommendations

A limited number of studies were reviewed and a there was a limitation on identification of what specific SPBs models or prototypes were identified in the study. Limited search terms used were also known as this resulted in numerous irrelevant articles for screening. Consequently, some articles used SPBs but were not used for medication adherence review. As previously defined, most of the searched and reviewed articles used medication adherence instead of medication compliance.

Recommendations from this review are focused on the availability, cost effectiveness and cost-efficient of Smart Pill Bottle Systems not only for highly developed countries but also for developing countries. Universal healthcare systems of all countries must include provisions that will provide affordable SPBs, or the cost should be covered by health premiums. A thorough educational awareness and willingness of the patients to use a system that needs continuous follow-up and collaboration of multidisciplinary teams e.g. clinicians, pharmacist, nurses, and their support programs, are needed so that medication adherence is achieved. Lastly, further research involving different methods are also warranted in the future to equip the healthcare industry with new trends and new discoveries.

Implications to practice

This review highlights three major points including user’s acceptability of SPBs, the impact on the utilization of these SPBs, and the potential of SPBs in clinical practice. Consideration of these three themes supports the integration of SPBs to promote medication adherence and management of patients. Hence, it is imperative that SPBs should be widely known, available, and affordable to meet the demands of the rapidly changing healthcare system.

Conclusion

This integrative review evaluated and analyzed the effects of Smart Pill Bottle Systems on medication adherence. Smart Pill bottle systems continue to evolve, and, in this review, researchers examined satisfaction levels, the impact of SPBs on medication adherence, and how these devices support medication treatment in the clinical setting. SPBs were mainly developed to improve medication adherence and were tested for effectiveness. The studies included were mostly randomized controlled trials and one article employed both data triangulation and qualitative feedback on the use of SPBs. The studies were taken from the US, Korea, and the Netherlands. Three themes were identified: Acceptability of SPBS, Impact on Medication Adherence and SPBS in routine clinical care. Patients who used SPBs were highly satisfied, but physical features of this device affected the preference of some users. SPBs were more effective in measuring medication adherence when paired with other supportive technology. SPBs had a positive impact on some client condition. Medication adherence is very crucial for the well-being of patients and SPBS could provide a positive impact on various patient’s conditions. This would warrant future researchers to investigate SPBs in a wider population.

References

Bentley, D., & Potts, J. W. (2021, August 12). Medication adherence and compliance. Fresenius Medical Care. https://fmcna.com/insights/articles/medication-adherence-and-compliance-/

Brown, M. T., & Bussell, J. K. (2011). Medication Adherence: WHO Cares? Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 86(4), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2019). CASP Critical appraisal checklists. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Choi. (2019). A pilot study to evaluate the acceptability of using a Smart Pillbox to enhance medication adherence among primary care patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203964

Cramer, J. A., Roy, A., Burrell, A., Fairchild, C. J., Fuldeore, M. J., Ollendorf, D. A., & Wong, P. K. (2008). Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value in Health, 11(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x

Ellsworth, G. B., Burke, L. A., Wells, M. T., Mishra, S., Caffrey, M., Liddle, D., Madhava, M., O’Neal, C., Anderson, P. L., Bushman, L., Ellison, L., Stein, J., & Gulick, R. M. (2021). Randomized pilot study of an advanced smart-pill bottle as an adherence intervention in patients with HIV on antiretroviral treatment. JAIDS: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 86(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002519

Faisal, S., Ivo, J., & Patel, T. (2021). A review of features and characteristics of smart medication adherence products. Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue Des Pharmaciens Du Canada, 154(5), 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/17151635211034198

Grant, K., & Steele, J. (2016, July 18). Smart pill bottle invented at UAH heads to clinical trials. The University of Alabama in Huntsville. https://www.uah.edu/news/research/smart-pill-bottle-invented-at-uah-heads-to-clinical-trials

Kataria, G., Dhyani, K., Patel, D., Srinivasan, K., Malwade, S., & Syed Abdul, S. (2021). The smart pill sticker: Introducing a smart pill management system based on touch-point technology. Health Informatics Journal, 27(4), 146045822110528. https://doi.org/10.1177/14604582211052848

Mauro, J., Mathews, K. B., & Sredzinski, E. S. (2019). Effect of a smart pill bottle and pharmacist intervention on medication adherence in patients with multiple myeloma new to lenalidomide therapy. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 25(11), 1244–1254. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.11.1244

Mehta, S. J., Volpp, K. G., Troxel, A. B., Day, S. C., Lim, R., Marcus, N., Norton, L., Anderson, S., & Asch, D. A. (2019). Electronic pill bottles or bidirectional text messaging to improve hypertension medication adherence (Way 2 Text): A randomized clinical trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(11), 2397–2404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05241-x

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2015). Making the case for evidence-based practice and cultivating a spirit of inquiry. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (3rd ed., pp. 6-7). Wolters Kluwer.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & the PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Pal, P., Sambhakar, S., Dave, V., Paliwal, S. K., Paliwal, S., Sharma, M., Kumar, A., & Dhama, N. (2021). A review on emerging smart technological innovations in healthcare sector for increasing patient’s medication adherence. Global Health Journal, 5(4), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOHJ.2021.11.006

Park, H. R., Kang, H. S., Kim, S. H., & Singh-Carlson, S. (2022). Effect of a smart pill bottle reminder intervention on medication adherence, self-efficacy, and depression in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 45(6), E874–E882. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000001030

Rice, D. R., Kaplan, T. B., Hotan, G. C., Vogel, A. C., Matiello, M., Gillani, R. L., Hutto, S. K., Ham, A. S., Klawiter, E. C., George, I. C., Galetta, K., & Mateen, F. J. (2021). Electronic pill bottles to monitor and promote medication adherence for people with multiple sclerosis: A randomized, virtual clinical trial. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 428, 117612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2021.117612

Rootes-Murdy, K., Glazer, K. L., Van Wert, M. J., Mondimore, F. M., & Zandi, P. P. (2018). Mobile technology for medication adherence in people with mood disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 613–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2017.11.022

Souza, M. T. de, Silva, M. D. da, & Carvalho, R. de. (2010). Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein (São Paulo), 8(1), 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134

Ross, S. M. (2022, October 25). Medication adherence vs compliance: 4 ways they differ. Blog. https://blog.cureatr.com/medication-adherence-vs-compliance-4-ways-they-differ

Toscos, T., Drouin, M., Pater, J. A., Flanagan, M., Wagner, S., Coupe, A., Ahmed, R., & Mirro, M. J. (2020). Medication adherence for atrial fibrillation patients: Triangulating measures from a smart pill bottle, e-prescribing software, and patient communication through the electronic health record. JAMIA Open, 3(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooaa007

Sparbel, K. J., & Anderson, M. A. (2000). Integrated literature review of continuity of care: Part 1, conceptual issues. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32(1), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00017.x

Sparbel, K. J., & Anderson, M. A. (2000). A continuity of care integrated literature review, Part 2: Methodological issues. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32(2), 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00131.xfnap

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Zijp, T., Touw, D., & van Boven, J. (2020). User acceptability and technical robustness evaluation of a novel smart pill bottle prototype designed to support medication adherence. Patient Preference and Adherence, 14, 625–634. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S240443

Author Notes

Enrico Del Rosario https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7908-2579

Kristine Bayoran https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5791-3511

Joyce Demdam https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3692-9543

Leocel Gallenero https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6261-4858

Daniel Valdez https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7893-5135

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Roison Andro Narvaez, Professor, St. Paul University Philippines, Mabini Street, Tuguegarao, Cagayan, 3500 Philippines, rnarvaez@spup.edu.ph

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The researchers acknowledge St. Paul University Philippines for their moral support and guidance in the manuscript.