Commentary: Management of Evacuee Health Information

by Ross Graham BA MSc

National, regional, and local public health agencies all play a role in emergency preparedness and response in Canada (Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA), 2010). This collaborative effort is critical given the array of both environmental and non-environmental emergencies experienced in Canada, and the potential impact these events can have on population health and wellbeing. A common required response to environmental emergencies is evacuee and shelter management (ESM). Recent Canadian emergencies that required ESM include the extensive flooding in southern Manitoba in the spring of 2011, and forest fires in northwest Ontario in the summer of 2011. To give a sense of the scale of an evacuation, the Ontario forest fires, which burned approximately 627,222 hectares, led to the evacuation of 10 First Nation communities totaling approximately 3,600 individuals (EMB, 2011).

National, regional, and local public health agencies all play a role in emergency preparedness and response in Canada (Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA), 2010). This collaborative effort is critical given the array of both environmental and non-environmental emergencies experienced in Canada, and the potential impact these events can have on population health and wellbeing. A common required response to environmental emergencies is evacuee and shelter management (ESM). Recent Canadian emergencies that required ESM include the extensive flooding in southern Manitoba in the spring of 2011, and forest fires in northwest Ontario in the summer of 2011. To give a sense of the scale of an evacuation, the Ontario forest fires, which burned approximately 627,222 hectares, led to the evacuation of 10 First Nation communities totaling approximately 3,600 individuals (EMB, 2011).

While local public health and health service providers often coordinate the initial emergency response (as per the National Emergency Response System [PSC, 2011]), information gathered by local public health units (PHU) can be useful to agencies at all levels to improve future planning and response. In the case of the Canada-wide pandemic H1N1 vaccination campaign in 2009, Heidebrecht, Pereira, Quach et al. (2011) reported that information collected at the “point of care” was critical to future pandemic planning at the provincial/territorial and national levels. Furthermore, they emphasize that the PHU choice of information collection system had “important implications for on-site efficiency and organization, as well as program planning and evaluation” (p. 349). However, information management is only one element of an emergency response, and may be an afterthought as PHU staff strive to meet the myriad of evacuee needs. Perhaps the most central and visible PHU staff during ESM is the front-line public health nurse.

Role of the Public Health Nurse

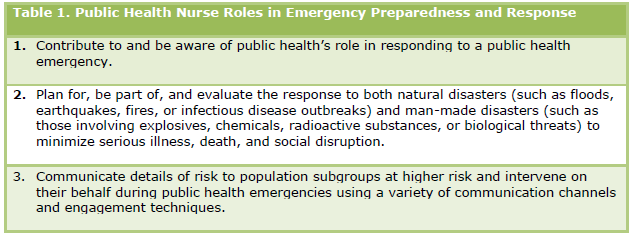

The public health nurse (PHN) (also known as a community health nurse) is a dynamic and skilled professional able to provide a variety of services that promote and protect human health (CPHA, 2010). This means that PHNs are able to provide primary health services in shelters for evacuees of natural disasters, (in both urgent and non-urgent evacuations). PHNs are often responsible for conducting a medical history with evacuees, then providing ongoing health assessment, monitoring and treatment, as well as referrals to other professionals when necessary. Table 1 outlines the roles of a PHN in emergency planning and response.

Table 1: Public Health Nurse Roles in Emergency Preparedness and Response

While these duties are well within the scope of a PHN, organizations must support PHNs with information management tools and processes that are both functional and of high quality. While functionality is a key consideration given the stressful and urgent nature of ESM, high quality information management tools should a) manage the privacy and recordkeeping risks associated with the collection of personal health information, and b) allow this information to support future emergency preparedness planning (Heidebrecht et al., 2011). Achieving a balance between quality and functionality is also important given the increased ‘climate of accountability in public health’ (PHD, 2011) which suggests an evaluation could occur following any public health emergency in order to improve future efforts. Not surprisingly, prior consideration regarding how evacuee data is collected and managed could improve the information available during evaluation. However, during an evacuation, PHNs may create thousands of health records within a short period of time, which means that the collection process must not be so complicated and overly comprehensive that functionality is sacrificed.

Models of Information Collection Systems

Without delving into the nuances of the numerous proprietary and open-source health information collection systems, I will review three high-level approaches to ESM evacuee health information collection (i.e., electronic, manual and hybrid systems) and then discuss necessary system elements that should be considered in order to balance quality and functionality. This discussion is intended to inform PHU preparation activities regarding ESM and how they can support any evaluation that may follow. Please note that all professional obligations regarding documentation, privacy and records retention apply to each approach. Furthermore, all screening and assessment tools and fields should be valid, and the ESM team should have a common understanding of the meaning of each information collection field, as well as acronyms and abbreviations.

Electronic Systems

A fully electronic system should include:

a) A front-end information entry component that prompts a PHN to provide a notice of collection to the evacuee (this is often necessary in order to obtain a valid consent) and enough fields for a complete medical history. This is critical given that an evacuee may arrive with no medication and most likely without any health records (although, if time permits and the evacuation is well-organized, these can be obtained from the evacuees’ local primary care providers).

b) A scheduling component that allows booking and notification of any necessary follow-up.

c) A back-end database that collects this information and stores it on a secure network server housed in Canada (preferably within the home territory/province) that is backed up daily. Note: server location dictates its jurisdiction, not the location where information was submitted. This has major privacy implications if using a server stored in the United States (for example).

d) A reporting component that allows evacuees information to be sent, printed or summarized in the event that consultation, assessment or treatment is required by an external health professional.

The electronic system must automatically keep a record of each entry’s author, and be password-protected. Utilizing existing PHN login credentials (added ahead of time by the system administrator) or using a badge-barcode login may improve ease of access for PHNs and maintain privacy. A fully electronic system should of course include space for entering notes in addition to entering data into set fields, but most electronic systems will be more rigid than a manual system (e.g., PHNs may not be able to add extra categories, or leave fields empty on an electronic assessment). Some rigidity is important as it increases data comparability and reduces the time needed to ‘clean up the data’ later on. Some tools that may support functionality and quality with an electronic system are a magnetic stripe reader for health cards and driver’s licenses, analytics for overall assessment of the evacuee population, and ‘smart’ fields that establish risk categories or prompt further questioning. Scenario-based system testing and user-led functionality review should be a part of the maintenance of an electronic system.

Manual Systems

A manual or paper-based system should include:

a) A set of core and supplementary screening and assessment forms that have been developed with PHNs (including a notice of collection prompt). The core form(s) are used for initial screening and assessment, and any supplementary form(s) are used for more in-depth assessment.

b) A common calendar accessible to all PHNs for scheduling any necessary follow-up. This will likely contain personal information and should be kept confidential.

c) A defined step-by-step process for records management considering records transfer, storage, duplication, protection, access requests and review.

Manual systems may initially be more functional from the user-perspective due to ease of use, but least functional in the long-term. In the event that a shelter setup only allows for a manual system, some tools that may support quality and functionality are credential stamps for each user, a robust (but not excessive) list of usable acronyms, and proximal secure records storage. Carbon copy forms (i.e., duplicate or triplicate forms) may be also useful or cumbersome depending on the number of external partners involved in the ESM that require access to the information being collected. The lead PHU should assume responsibility for storing all official copies of records.

Hybrid Systems

Although a hybrid system could include a number of different electronic and manual elements, the most common hybrid system is a manual system that is then transferred to an electronic system (i.e., manual to electronic) (Heidebrecht et al., 2011). Hybrid systems may be seen as achieving both functionality and quality considerations. However, the manual to electronic system creates a duplication of effort, and allows a second opportunity for human error. Paper records that will likely be entered into an electronic database should attempt to use documents that can be scanned and either automatically, or with little effort, added to the database.

Summary

Similar to emergency preparedness and response, preparing for proper collection and management of evacuee health information is challenging work that is best done collaboratively by clinicians, informational technology professionals and administrators. Done well however, this information can assist PHNs to provide coordinated care to evacuees immediately, and support future ESM planning efforts. Discussion and selection of one of the models above should involve administrators, those who will user the system during the emergency (e.g., PHNs) and possible future users of evacuee information (e.g., planners, epidemiologists). Consensus from these stakeholders regarding the type of system, form design and recordkeeping approach, as well as scenario-based testing of these items should prepare PHUs to best support and assist evacuees.

About the Author

Ross Graham is the Manager of Special Projects at the Middlesex-London Health Unit in London, Ontario. His portfolio includes continuous quality improvement as well as records management.

References

Canadian Public Health Association. (2010). Public health: Community health

nursing practice in Canada: Roles and activities. ISBN 1-894324-57-9.

Emergency Management Branch: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. (2011). Emergency Preparedness Planner: A Newsletter for the Health System. Published Online Summer 2011.

Heidebrecht, C.L., Pereira, J.A., Quach, S., Foisy, J., Quan, S.D., Finkelstein, M., et al. (2011). Approaches to immunization data collection employed across Canada during the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccination campaign. Can J Public Health, 102(5): 349-54.

Kain, J. (2011). Emergency: How to build a document unit for hazardous incident response. Information Management, 45(6): 20-25.

Public Health Division: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. (2011). Ontario Public Health Organizational Standards. ISBN 978-1-4435-5469-5.

Public Safety Canada. (2011). National Emergency Response System. Available online at http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/prg/em/ners-eng.aspx.

EDITOR:Helen Edwards