Factors Affecting Nurses’ Attitudes Toward an Automated Dispensing Unit: A Cross Sectional Quantitative Study

by Lyndsay Mather, BA, National Research Council

Heather Molyneaux, PhD, National Research Council

Annette Lebouthillier, RN MSc, Vitalité Health Network

Lise Guerrette-Daigle, RN MBA, Vitalité Health Network

Suzanne Robichaud, RH BHSc, Vitalité Health Network

Gaetane Leblanc-Cormier, RN, Vitalité Health Network

Susan O’Donnell, PhD, National Research Council

Helene Fournier, PhD, National Research Council

Pascal Sirois, BA, National Research Council

Corresponding author:

Dr. Heather Molyneaux

Tel.| Tél. : (506) 444-0571 | Facsimile | télécopieur : (506) 444-6114,

Heather.Molyneaux@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Analyst, People-Centred Technologies Group

NRC Institute for Information Technology e-Business| Institut de technologie de l’information du CNRC http://iit-iti.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

National Research Council Canada

46 Dineen Drive, Fredericton NB E3B 9W4

Canada Government of Canada | Gouvernement du Canada

Abstract

The implementation of new technologies for the automated preparation and dispensing of medication in Canadian hospitals is becoming widespread. Although researchers are not currently seeing the high level of resistance to new technology by nurses prevalent several years ago, studies continue to show that nurses link technology in clinical environments to the dehumanization of nursing. Knowing the opinions and perceptions of nurses before implementing healthcare technology can allow administrators to allocate resources to address any issues and misunderstandings that the nurses may have. To better gauge healthcare employees’ willingness to use a new technology in a healthcare environment, this study used online and paper surveys to explore the introduction of Automated Dispensing Units (ADU) into two hospitals within New Brunswick’s Vitalité Health Network. The fundamentals of the Telemedicine Technology Acceptance Model were used to design this quantitative study, which represents the pre-implementation phase of a longitudinal study. The survey questions assessed demographic characteristics that may affect both opinions and beliefs of technology, computer expertise and use. The main section of the survey dealt with opinions and perceptions of an ADU, medication preparation, perceptions of usefulness, ease of use of their current medication preparation system, and workflow and training.

Keywords

Automatic Medication Administration; Nursing Technology, Attitudes toward Technology

Acknowledgement

The research project was a partnership between the National Research Council of Canada, Vitalité Health Network VHN and McKesson Canada. McKesson did not contribute funds toward this research or influence the research design or outcomes. They acted in an advisory capacity to demonstrate the functionality of the proposed new technology and clarify issues arising related to the use of the technology in the hospital setting.

Introduction

Canadian hospitals are introducing new technologies for the automated preparation of medications. Automated dispensing units (ADUs) have been found to reduce medication errors (Borel & Rascati, 1995; Fitzpatrick, Cook, Southhall, Kanldar, & Waters, 2005; Franklin, O’Grady, Voncina, Popoola, & Jacklin, 2008), near misses (Dib et al., 2006), costs (Dib et al., 2006), space devoted to storage (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005; Franklin et al., 2008), and nurses’ time spent on medication preparation (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005).

Successful implementation of new technology in a healthcare environment relies on internal factors, such as the nurses’ perceived use and ease of use of the technology (Davis, 1989), and external factors that contribute to these perceptions, such as demographics, and past computer use and experience (Kowitlawakul, 2011). If these internal and external factors are not considered, successful implementation is unlikely (Davis, 1989; Kowitlawakul, 2011). Identifying nurses’ perceptions and opinions of an ADU before implementation can help address negative attitudes that may exist. Changing these negative attitudes will increase the chance that an ADU is successfully implemented and adopted. This quantitative study represents the pre implementation phase of a longitudinal study designed to explore the introduction of ADUs into New Brunswick’s Vitalité Health Network hospital wards and identify challenges, successes and opportunities to inform improvement of the implementation adoption phase. The specific research questions were:

-

What are nurses’ perceptions of usefulness and ease of use of the current system for medication preparation?

-

Which internal or external factors affect nurses’ perceptions of usefulness and ease of use of the current system for medication preparation?

-

What are the attitudes toward, and the perceived future impact of, an ADU?

-

Which internal or external factors affect the attitudes toward, and the perceived future impact of, an ADU?

Literature Review

Although current researchers are not reporting the high resistance to new technology prevalent several years ago, studies continue to show that nurses link technology in clinical environments to the dehumanization of nursing (Barnard & Sandelowiski, 2000; De Veer & Francke, 2010; Kirkely & Stein, 2004; Timmons, 2003). Researchers also report that nurses who failed to see the advantages of technology for nursing practice harshly criticized and distrusted hospital technology, and, in turn, these negative attitudes were found to contribute to resistance toward technology (Barnard & Sandelowiski, 2000; De Veer & Francke, 2010; Kirkely & Stein, 2004; Novek et al., 2000; Timmons, 2003). Unsuccessful adoption can result in the new technology going unused in lieu of using the previous method that the technology has replaced, as well as the technology not being used properly, increasing such things as costs and near misses (De Veer & Francke, 2010; Kirkely & Stein, 2004). As Canadian hospitals begin to introduce ADUs, it is increasingly important to investigate nurses’ attitudes toward technologies to inform successful technology adoption.

One of the most widely accepted theories of technology adoption is Davis’ Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which was developed to measure, predict and explain technology use (Davis, 1989). This model can be applied to help identify, explain, and predict factors that affect the intentions of technology users (Kowitlawakul, 2011). The TAM framework consists of two theoretical constructs: perceived usefulness and ease of use (Davis, 1989).

Perceived usefulness is defined as the tendency to use or not use a technology based on the magnitude the user believes it will enhance their job performance (Davis, 1989). Perceived ease of use indicates that the degree to which the user sees the system as being difficult to use will counter, and perhaps outweigh, the effort needed to use it (Davis, 1989). Perceived usefulness falls into three main clusters; job effectiveness, productivity and time savings, and the importance of the system to one’s job (Davis, 1989). Perceived ease of use is reflected by physical effort and mental effort and perceptions of how easy it is to learn a system (Davis, 1989). Davis found that both perceived usefulness and ease of use were significantly correlated with self-reported indicants of system use, with usefulness being more strongly linked to usage than ease of use (Davis, 1989).

Although there has been some debate whether the TAM can be applied to adoption of technology in healthcare (Aggelidis & Chatzoglou, 2009; De Veer & Francke, 2010; Dixon, 1999; Holden & Karsh, 2009, Kowitlawakul, 2011), researchers have reported strong evidence to support perceived usefulness as a valid construct to predict adoption of a healthcare technology (Aggelidis & Chatzoglou, 2009; Holden et al. 2009). However, since the TAM was developed outside of the healthcare environment some concepts may not be relevant to researchers predicting behaviour in a healthcare setting (Holden, et al., 2009).

To address this, Kowitlawakul (2011) modified the TAM and renamed it the Telemedicine Technology Acceptance Model (TTAM). The TTAM utilizes four constructs drawn from the original TAM (perceived use, perceived ease of use, attitude toward using, and intention to use) and three external variables (years worked in the hospital, support from administrators and support from physicians). Kowitlawakul (2011) found that the model was reliable, explaining 58% of the variation in the intention to use an eICU technology. Results showed perceived ease of use to be the most salient factor influencing nurses’ intentions to use a the eICU, while the principal factors influencing perceived usefulness were perceived ease of use, support from physicians, and years working in the hospital (Kowitlawakul, 2011). Kowitlawakul (2011) thus concluded that the TTAM showed promise as a valuable model for predicting nurses’ intention of using a healthcare technology.

The current study uses the basis of TTAM (i.e. uses external, demographic and hospital specific variables and internal, technology acceptance variables) to investigate relationships between external and internal factors and attitudes and opinions about a new medication preparation technology. Specifically, five external, demographic variables were used in the study, all of which being found in the literature to predict technology acceptance in a healthcare environment: age (Brumini & Kovic, 2005; Marini et al., 2010); gender (Alquraini et al., 2007)); education (Alquraini et al., 2007; Brumini & Kovic, 2005); employment status (De Veer & Francke, 2010; Dillon, et al., 1998); and computer use (Brumini & Kovic, 2005). Two external, hospital specific variables were also found in the literature to contribute to perceptions of and attitudes toward technology: size of the hospital (Kimble & Chandra, 2001); and opinion of pharmacy (Baker, Bavier, & Keiper, 2005; Keiper, 2005; Weber, et al., 2004). The internal variable found to be relevant in the literature, as well as used in both the TAM and TTAM was perceived use/ease of use (Davis, 1989; Kowitlawakul, 2011).

Age is reported as a major contributor to nurses’ attitudes towards technology. In particular, compared with “older nurses,” nurses younger than thirty years or “younger nurses,” had significantly higher total acceptance scores for implementation of healthcare technology (Brumini & Kovic, 2005; Marini et al., 2010). One study found age was the only variable that demonstrated a statistically significant difference in nurses’ attitudes towards the technology and that younger nurses had a greater appreciation for the technology being implemented (Dillon, Blankenship & Crews, 2005).

Despite recent gains in the number of male nurses, particularly in North America, female nurses still greatly outnumber males nurses (Alquraini et al., 2007). Given this, it is typically rare to find statistically significant results when gender is used as a mediator in quantitative models. However, in one study, Alquraini et al. (2007) found more positive attitudes toward implementation of technology in a hospital among females compared with males. Yet, as with most studies reviewed, females in the aforementioned study out-numbered males; 85.8% of respondents were female, while 14.2% of respondents were male. Gender, then, is best used as a control, which may have some predictive power regarding the successful adoption of technology in a healthcare setting (Alquraini et al., 2007).

Education may predict nurses’ attitudes towards technology. Previous studies revealed that compared with other educational preparation, nurses with a bachelor’s degree had significantly more positive perceptions about technology implementation in their hospital (Alquraini et al., 2007; Brumini & Kovic, 2005). Employment status also contributes to nurses’ perceptions and opinions of technology. Studies found that nursing staff who worked at least thirty hours per week and who worked full time had more positive attitudes towards using technology (De Veer & Francke, 2010; Dillon, et al., 1998). Nursing staff in management positions and more experienced nurses had a more positive perspective about technology implementation in their hospital (De Veer & Francke, 2010; Kowitlawakul, 2011).

Several researchers reported that computer use and duration, for any purpose- work, education, pleasure, and communication- has a positive impact on nurses’ acceptance of technology (Alquraini et al., 2007; Ammenwerth et al., 2003; Brumini & Kovic, 2005; Getty, Assumpta & Ekins, 1999). Also, nurses with medical informatics classes during their formal education had significantly more positive attitudes towards technology (Brumini & Kovic, 2005). One research group suggested that nurses without previous experience with technology should be provided carefully developed education on the use of the implemented technology (Alquraini et al., 2007). Researchers also recommended that nursing staff with experience and who have a positive attitudes can act as role models for others (De Veer & Francke, 2010).

The size of the hospital, too, can affect the perceptions of and attitudes toward an ADU being implemented into a healthcare environment. Smaller, rural hospitals tend to have a more difficult time accepting a new technology into their healthcare setting (Kimble & Chandra, 2001). With a smaller staff comes a more entrenched nursing culture, which may be more resistant to technology if the implementation process fails to consider the deep-rooted practice of nursing (Timmons, 2003). Larger staffed hospitals, on the other hand, may be more open to technology implementations, as they have a higher staff turn-over rate, circumventing a securely anchored nursing culture (Kimble & Chandra, 2001). Also, nurses working in a smaller hospital may not see the need to have a faster system, given that they are not as rushed; whereas, nurses working in a larger hospital may see the benefit of having a faster system.

Net of other external factors, the opinion of the pharmacy can affect the opinions and attitudes towards the implementation of an ADU (Baker, Bavier, & Keiper, 2005; Keiper, 2005; Weber, et al., 2004). An ADU is specifically related to the pharmacy in that it is the pharmacists’ responsibility to refill the medication cabinets. Given this, a less than pleasant opinion of the pharmacy in the hospital may have nurses more enthused about the implementation of an ADU, which may lessen contact with the pharmacy and increase the service speed of the pharmacy (Baker, et al., 2005; Keiper, 2005; Weber, et al., 2004).

Given the review of the literature, the above factors- perceptions of usefulness/ease of use, demographics, hospital size, and opinions of pharmacy- are thought to be suitable contributors to shaping nurses opinions and perceptions of the forthcoming implementation of an ADU into their hospital. Knowledge of nurses’ opinions and perceptions of a healthcare technology before implementation can inform administrators to address any issues and misunderstandings (Lee, 2007). The TTAM allows for a measure of nurses’ overall attitudes, as well as a gauge to measure which characteristics of nurses contribute to negative views of healthcare technology. This model does so by allowing for the consideration internal, technology specific variables, specifically perceived usefulness/ease of use, as well as external, demographic and hospital specific variables, which were cited above.

Methods

Ethical approval was received from both the Vitalité Health Network’s Research Ethics Board, as well as the Research Ethics Board of the National Research Council. Participants were recruited from two New Brunswick hospitals, a larger urban hospital that employs 692 nurses and a smaller rural hospital with 45 nurses. Survey data were collected from May to August 2011. Participants were recruited using an ad over the hospital intranets, as well as by informing head nurses that participants were needed for the survey. The online survey was open to all nurses in both hospitals. To maximize responses, 60 paper surveys, along with self-addressed stamped envelopes, were distributed to the wards in the hospitals. The online survey and the paper survey were identical and nurses were informed that they could complete either survey at work or at home.

The survey incorporated three sections: an introduction that explained the purpose of the study, the instrument items, and a thank you section with a link to a prize website. The participant was informed she/he could continue to a separate site to enter their email for a chance to win a prize. The paper survey provided the URL for this site.

To ensure anonymity and measure changes in responses before and after the ADUs are introduced, the respondents were asked to generate a six lettered pseudonym similar to those successfully used in previous studies (Carifio & Biron, 1982). The identification code was created by asking respondents to use the first two letters of their middle name, the first two letters of their birth month, and the first two letters of the city/town in which they were born, yielding a six lettered, individual specific code.

To assess which individual characteristics affect opinions and beliefs about technology, demographic and computer expertise and use questions were asked. Several other studies have used demographics, work experience, and technology use to explain characteristics that influence nurses’ perception of technology (Ardern-Jones et al., 2009; Alquraini et al., 2007; Ammenwerth et al., 2003; Brumini & Kovic, 2005; De Veer & Francke, 2010; Dillon, et al., 2005; Getty, et al., 1999; Kowitlawakul, 2011; Marini et al., 2010; Novek et al., 2000; Wakefield et al., 2010). Preceding the demographic and computer use section, the instrument was then divided into six sub-sections. Survey questions were developed based on the review of related literature and were modified to fit the current study, including both the internal and external factors explored in the literature review. Both positively and negatively worded items were developed. Each of these six sub-sections used a five-point, Likert rating scale with responses ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (value of 1) to ‘strongly agree’ (value of 5) along with a “Not applicable” (N/A) column. At the end of each sub-section the respondent was able to add text comments if they had further thoughts. The six sub-sections dealt with: (1) opinions and perceptions of an ADU; (2) medication preparation; (3) perceptions of usefulness and ease of use of their current medication preparation system; (4) workflow and training; (5) opinions of pharmacy; and (6) time spent on medication preparation. To answer the research questions in the current study, the analysis used sections 1, 3, and 5.

Data Analysis

Univariate and bivariate statistics were used to address the first research question. Differences were tested with Student t tests, Pearson’s product moment correlations, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with alpha coefficients set at .05. The second research question was investigated with multiple linear regressions. Alpha coefficients of .05 and .10 were used due to the small sample size.

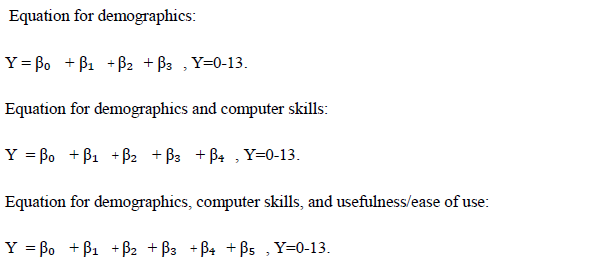

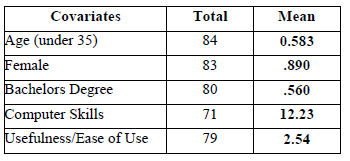

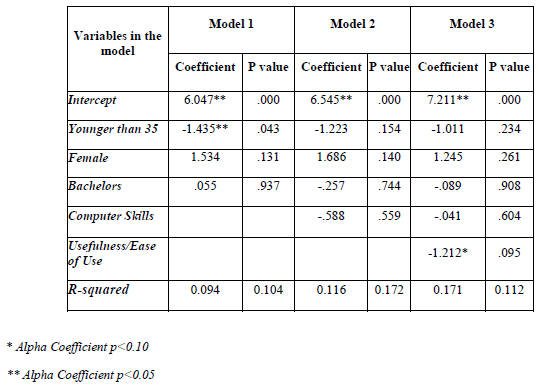

The dependent variable for the multiple linear regression analysis was attitude towards technology (ATT). Respondents were asked to rank six questions that dealt with their perceptions and opinions about an ADU being implemented into their hospital. After exploring the correlations and statistical significance between the six variables two variables were dropped before creating the ATTfactor due to poor correlation. The four remaining variables were combined to create an ATT factor that ranged from 0, or very negative, to 13, or very positive attitude. Five covariates were used; younger than 35, female, bachelor’s degree, computer skills, positive usefulness and ease of use scores (Table 1). All these variables are dichotomous except computer skill which was continuous (scores ranging from 0-18), and positive usefulness and ease of use scores which ranged from 0-30.

Three models were computed: model one included demographic predictors; model two added computer skills to the previous model; and model three added usefulness/ease of use to the previous model. The three equations for each model are as followed:

Results

For the sample of 66 nurses who completed the online survey, 35 worked at the urban hospital, 29 at the rural hospital and two undeclared. Of the eighteen nurse participants who completed the paper survey, 15 worked at the urban and three at the rural hospital. Respondents were predominantly female (90%), the majority were less than 35 years old (58%), over half had a bachelor’s degree (54%), nearly three quarters were registered nurses (74%), and most were full-time employees (84%). Slightly more respondents were recruited from the larger hospital (59%) compared with the smaller hospital (41%), with 31% of respondents working in the ER at their respective hospital. The average length of time respondents have been working at their current profession is 13 years.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Covariates or Demographic Variables

Nurses’ Perceptions of Usefulness/Ease of Use

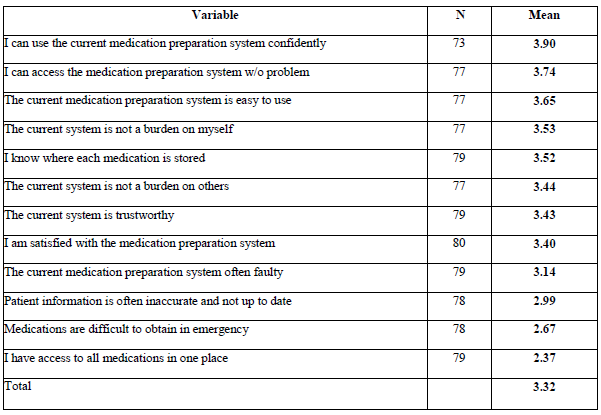

Twelve questions were asked concerning perceptions of the usefulness and ease of use of the current medication preparation system, with respondents being asked to rank each item from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Negatively word items were inverted for the analysis. The overall mean on these variables was 3.32, indicating an above average opinion. Breaking the responses down twofold, the mean responses for nine of these variables were between three and four, indicating a neutral to positive agreement or opinion; while the means for the other three variables were between two and three, indicating a disagreement to neutral opinion (Table 2). On the whole, this suggests a fairly positive perception from nurses of the usefulness and ease of use of their current medication preparation system.

Table 2. Perceived Usefulness/Ease of Use

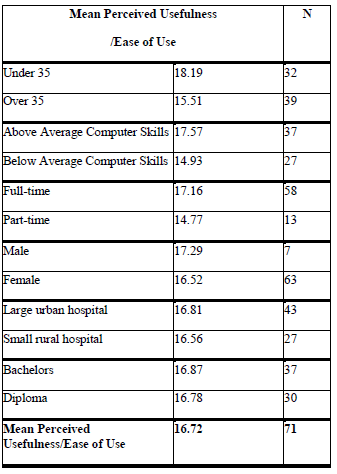

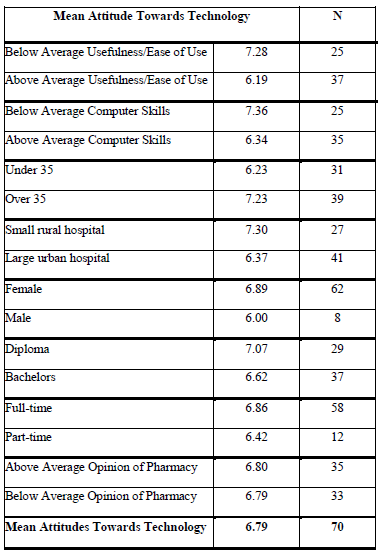

After exploring the correlation matrix and statistical significance between the twelve variables, three items were removed before the creation of a factor due to low (less than |0.3|) correlation with the other variables. The remaining nine items were kept to create one factor measuring perceptions of usefulness and ease of use. This factor ranged from 0, or most negative, to 30, or most positive. Means of dichotomous demographic variables were compared (i.e. “younger” nurses’ opinions compared to “older” nurses’ opinions)- note that for this analysis, a “below average computer score” is considered to be a score below 12.23 (Table 3). Despite there being no statistically significant differences between means found, some trends were noted (Table 3). For example, respondents under the age of 35, full-time nurses, and participants with better computer skills had more positive perceived usefulness and ease of use mean scores than their counterparts (Table 3).

Table 3: Mean Perceived Usefulness/Ease of Use

Attitude Towards and the Perceived Future Impact of New Technology for Medication Preparation

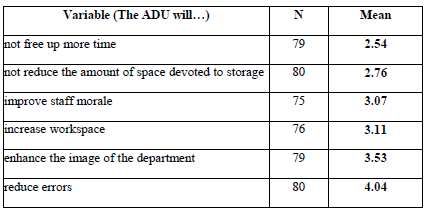

Of the six questions related to perceptions of and agreement to an ADU being implemented into their hospital, the mean for four questions was neutral to positive while two means were negative to neutral (Table 4). The overall mean for the six items was 3.175. This finding suggests an overall neutral agreement towards the adoption of an ADU.

Table 4. Perception of Impact of Introduction of ADU

None of the mean differences for the combined ATT scores were statistically significant (Table 5). However, some interesting results were noted. Contrary to the literature, older study participants reported more positive ATT compared with younger respondents; on average, one point higher than the younger respondents’ scores (7.23 compared to 6.23). Participants with below average opinion of the usefulness and ease of use of their current medication preparation system reported more positive ATT.

Table 5. Attitudes towards Technology

Within the first multiple linear regression analysis model, age is the only statistically significant variable. The average ATT score for participants under 35 years of age was 1.435 units lower than those over the age of 35 (Table 6). The second multiple linear regression analysis model, with the addition of computer skills, did not yield any statistically significant results. The third multiple regression model, with addition of usefulness and ease of use, explained a statistically significant amount of variance in ATT (alpha set at .1). Respondents with more positive attitude towards the usefulness and ease of use of their current medication preparation system had an average ATT score 1.212 units lower than those with less positive opinions about usefulness and ease of use of their current medication preparation system.

Table 6. Linear Regression Model: Predictors of Attitudes towards Technology

Discussion

This study examined factors that may contribute to nurses’ attitudes and opinions towards implementation of a new technology in their hospital. Many researchers have studied the extent that similar factors predict adoption of a variety of healthcare technologies (Ardern-Jones et al., 2009; Alquraini et al., 2007; Ammenwerth et al., 2003; Brumini & Kovic, 2005; De Veer & Francke, 2010; Dillon, et al., 2005; Getty, et al., 1999; Kowitlawakul, 2011; Marini et al., 2010; Novek et al., 2000; Wakefield et al., 2010), but few researchers have evaluated these factors within Canadian hospitals. This study provides some insight into how factors contribute to positive or negative attitudes and opinions of an ADU. Also, this study provided information on nurses’ perceptions of the usefulness and ease of use of their current system for medication preparation.

From the univariate analysis of perceptions of the current medication preparation system, results showed that, overall, nurses had a positive perception of their current medication preparation systems, suggesting that they may have more trouble adopting a new technology for medication preparation (Barnard & Sandelowiski, 2000; De Veer & Francke, 2010; Kirkely & Stein, 2004; Novek et al., 2000; Timmons, 2000). No significant differences or relationships were found for the bivariate analysis of perceived usefulness and ease of use. However, it is noteworthy that younger nurses perceive their current medication preparation system more positively than older nurses; nearly three points higher on average. This may be due to older nurses having more time and experience with their current medication preparation system, allowing them to view more flaws with it than a younger nurse would. It is also interesting to note that nurses with above average computer skills perceive their current medication preparation system more positively than do nurses with below average computer skills. As the literature implies, nurses with better computer skills tend to more readily adopt technology (Alquraini et al., 2007; Ammenwerth et al., 2003; Brumini & Kovic, 2005; Getty, Assumpta & Elkins, 1999). However, the current study suggests that nurses with above average computer skills are generally positive about their current medication preparation system.

Although no significant mean ATT differences were found, two comparisons defy the literature. Older nurses and nurses with below average computer skills reported higher ATT scores, on average, than their counterparts.

The regression analysis variables explained a statistically significant amount of variance in ATT. Age was statistically significant in the first model. This finding contradicts the literature as many researchers have reported younger nurses as more receptive of technology (Brumini & Kovic, 2005; Dillon, Blankenship & Crews, 2005; Marini et al., 2010). The first multiple regression model suggests that nurses under the age of 35 have lower ATT scores than older nurses. Yet this finding is comprehensible, given that in the bivariate analysis younger nurses had more positive average perceived usefulness and ease of use scores than older nurses. Thus, as the TAM and TTAM suggests, younger nurses may not be ready to adopt a new technology for medication preparation if they perceive their current system as useful and easy to use. The second multiple regression model yields no statistically significant variables.

When perceived usefulness and ease of use is added as a variable in the third multiple regression model, predictably this variable is negatively and significantly related with ATT. The current study found that nurses who perceive their current medication preparation system as useful and easy to use had more negative attitude towards a new technology for medication preparation compared with nurses who do not perceive their current system as useful and easy to use. This finding suggests that nurses who are satisfied with their current medication preparation system do not see the need to have an ADU, a technology that neither hospital was yet introduced to at the time of this study. As well in this model, age is no longer statistically significant, suggesting that perceived

Conclusions

The findings of the current study are important for those considering implementation of an ADU. In order to successfully implement an ADU, it is important that the end-user, or nurses, perceive the technology as useful and easy to use. The findings suggest that the TTAM external variables may be important to consider, along with internal variables when evaluating perceptions of technology in a healthcare setting.

From the univariate analyses, it was found that the nurses in this study were quite positive about their current paper based preparation system, but were neutral about an ADU. Also, the current study found that younger nurses perceive their current paper-based medication preparation system as useful and easy to use, and found their attitude towards an ADU less than optimistic before perceptions of usefulness and ease of use are added to the model. Indeed, those nurses that view their current, paper based medication preparation system as useful and easy to use have a more negative attitude towards an ADU than those who do not share this view. Thus, external, demographic variables may indeed play a role in the attitudes towards an ADU, but internal perceptions seem to be key. Given these findings, the nurses at both hospitals may indeed have difficulty adopting an ADU into their hospitals.

As the literature suggests, a number of steps can be taken to improve the attitude towards a technology in a healthcare environment. Computer technology training and support, input from nurses, the consideration of nursing culture, and research, planning, and monitoring may all aid in changing nurses’ attitudes (Dillon et al., 1998; Dixon, 1999; Kirkely & Stein, 2004; Kowitlawakul, 2011; Nanji et al., 2009). Also, nurses should be given a clear view of the continuum of care and how they and the new technology fit in (Kirkely & Stein, 2004). Specifically, it should be clarified that the technology will not be negating the personal, humane aspect of the nursing profession. Rather, the technology should be presented in a manner that best fits with the intimate nature of the practice of nursing. Being upfront and honest about the ultimate goal of the technology that is being implemented is important for successful implementation. Considering the current study’s findings, it seems reasonable to say that uncovering the reasons why nurses perceive their current preparation system as useful and easy to use will provide the necessary information to ensure that these perceptions can be transferred to their opinions of the ADU.

Difficulty in obtaining survey responses from the large urban hospital, as well as missing responses were major obstacles for this project, resulting in a sample size that was less than ideal. There was a very low response rate from the urban hospital (8%), whereas the rural hospital gave a much better return (71%). Both online surveys and paper surveys were provided to nurses over a four month period, with numerous reminders being given. A hypothesized problem, reinforced by the nurses on the current research team, was that anonymity was not thought to be secured, which concerned nurses especially when being asked to comment on the pharmacy. Ensured anonymity, as well as the importance of having their opinion heard should be iterated clearly when carrying out research projects such as this one.

Considering that Canadian hospitals are rapidly rolling-out technology to ideally aid in the practice of nursing, more studies such as the current one must be completed. Indeed, a qualitative study has also been completed by the same research team how completed the current study, intending to explore more deeply nursing culture and its effects on technology preferences and attitudes. As the implementation of ADUs increase in Canadian hospitals, knowing the attitudes and opinions of nurses before implementation will aid in successful adoptions of hospital technologies.

References

Aggelidis, V.P., & Chatzoglou, P.D. (2009) Using a modified technology acceptance model in hospitals. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 78(2), 115-126.

Alquraini, H., Alhashem, A.M., Sham, M.A., & Chowdhry, R.I. (2007) Factors influencing nurses’ attitudes towards the use of computerized health information systems in Kuwaiti hospitals. Journal of Advance Nursing, 57(4), 375-381.

Ammenwerth, E., Mansmann, U., Iller, C., & Eichstafter, R. (2003) Factors Affecting and Affected by User Acceptance of Computer-based Nursing Documentation: Results of a Two-Year Study. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 10(1), 69-84

Ardern-Jones, J., Hughes, D.K., Rowe, P.H., Mottram, D.R., & Green, C.F. (2009) Attitudes and opinions of nursing and medical staff regarding the supply and storage of medicinal products before and after the installation of a drawer-based automated stock-control system. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 17(2), 95-99.

Baker, J., Bavier, K., & Keiper, K. (2005) Team evaluation of automated medication dispensing devices. Unpublished Manuscript, Duke University School of Nursing.

Barnard, A., & Sandelowiski, M. (2000) Technology and humane nursing care: (ir)reconcilable or invented differences? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(3), 367-375.

Borel, J.M., & Rascati, K.L. (1995) Effect of an Automated Nursing Unit-Based Drug-Dispensing Device on Mediation Errors. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 52(17), 1875-1879.

Brumini, G., & Kovic, I. (2005) Nurses’ attitudes towards computers: Cross sectional questionnaire study. Croatian Medical Journal, 46(1), 101-104.

Carayon, P., Smith, P., Hundt, A.S., Kuruchittham, V., & Li, Q. (2009) Implementation of an electronic health records system in a small clinic: The view point of clinical staff. Behaviour and Information Technology, 28(1), 5-20.

Carifio, J., & Biron, R. (1982) Collecting sensitive data anonymously: Further Findings on the CDRGP. Journal of Drugs and Alcohol, 27(2), 38-70.

Davis, F.D. (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

De Veer, A.J.E., & Francke, A.L. (2010) Attitudes of nursing staff towards electronic patient records: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(7), 846-854.

Dib, J.G., Abdulmohsin, S.A., Farooki, M.U., Muhammed, K., Iqbal, M., & Khan, J.A. (2006) Effects of an Automated Drug Dispensing System on Medication Adverse Event Occurrences and Cost Containment at SAMO. Hospital Pharmacy, 41(12), 1180-1184.

Dillon, T.W., McDowell, D., Salimian, F., & Conklin, D. (1998) Perceived ease of use and usefulness of bedside-computer systems. Computers in Nursing, 16(3), 151-156.

Dillon, T.W., Blankenship, R., & Crews, T. (2005) Nursing attitudes and images of electronic patient record systems. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 23(3), 139-145.

Dixon, D.R. (1999) The behavioral side of information technology. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 56(1-3), 117-123.

Fitzpatrick, R., Cook, P., Southhall, C., Kanldhar, K., & Waters, P. (2005) Evaluation of an Automated Dispensing System in a hospital pharmacy dispensary. Pharmaceutical Journal, 275(7354), 763-765.

Franklin, B. D., O’Grady, K. Voncina, L., Popoola, J., & Jacklin, A. (2008) An evaluation of two automated dispensing machines in UK hospital pharmacy. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 16(1), 47-53.

Getty, M., Assumpta, A.A., & Ekins, M.L.C. (1999) A comparative study of the attitudes of users and non-users towards computerized care planning. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 8(4), 431-439.

Holden, R.J., & Karsh, B-T. (2009) The technology acceptance model: Its past and its future in health care. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 43(1), 159-172.

Keiper, K. (2005) Individual evaluation of an automated medication dispensing device. Unpublished Manuscript, Duke University School of Nursing.

Kimble, C.A., & Chandra, A. (2001) Automation of pharmacy systems: Experience and strategies of a rural healthcare system. Hospital Topics, 79(2), 27-32.

Kirkley, D., & Stein, M. (2004) Nurses and clinical technology: Sources of resistance and strategies for acceptance. Nursing Economics, 22(4), 216-222.

Kowitlawakul, Y. (2011) The technology acceptance model: Predicting nurses’ intention to use telemedicine technology (eICU). Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 29(7), 411-418.

Lee, T-T. (2007) Nurses’ Experiences using a nursing information system: Early stage of technology implementation. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 25(5), 294-300.

Marini, S. D., Hasman, A., Huijer, H.A., & Dimassi, H. (2010) Nurses’ attitudes toward the use of the bar-coding medication administration system. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 28(2), 112-123.

Miller, K., Shah, M., Hitchcock, L., Perry, A., Englebright, J., Perlin, J., & Burgess, H. (2008)Evaluation of medications removed from automated dispensing machines using the override function leading to multiple system changes. Technology and Medication Safety, 4, 1-7.

Nanji, K. C., Cina, J., Patel, N., Churchill, W., Gandhi, T.K., & Poon, E.G. (2009) Overcoming barriers to the implementation of a pharmacy bar code scanning system for medication dispensing: A case study. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 16(5), 645-649.

Novek, J., Bettess, S., Burke, K., & Johnston, P. (2000) Nurses’ perceptions of the reliability of an automated medication dispensing system; Improving performance in the 21st century. Journal of Nursing and Quality, 14(2), 1-13.

Pai, F-H., & Huang, K-I. (2011) Applying the technology acceptance model to the introduction of healthcare information systems. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(4), 650-660.

Perras, C., Jacobs, P., Boucher, M., Murphy, G., Hope, J., Lefebvre, P., McGill, S., & Morrison, A. (2009) Technologies to Reduce Errors in Dispensing and Administration of Medication in Hospitals: Clinical and Economic Analyses Ottawa. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

Timmons, S. (2003) Nurses resisting information technology. Nursing Inquiry, 10(4), 257-269.

Wakefield, D. S., Loes, J.L., & O’Brien, J. (2010) A network collaboration implementing technology to improve medication dispensing and administration in critical access hospitals. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 17(5), 584-587.

Weber, R.J., Skledar, S.J., Sirianni, C.R., Frank, S., Yourich, B. & Martinelli, B. (2004) The impact of hospital pharmacist and technician teams on medication-process quality and nurse satisfaction. Hospital Pharmacy, 39 (12), 1169-1176.

Authors’ Bios

Lyndsay Mather, BA

Is an analyst at the National Research Council of Canada and a graduate student at the University of Toronto.

lyndsay.mather@utoronto.ca

Heather Molyneaux, PhD

Is an analyst at the National Research Council of Canada

Heather.Molyneaux@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Annette Lebouthillier, RN MSc

Is the vice-president of Nursing at Vitalité Health Network

Annette.Lebouthillier@VitaliteNB.ca

Lise Guerrette-Daigle, RN MBA

Is the executive vice-president of Acute Care Facilities at Vitalité Health Network

Lise.Guerrette-Daigle@VitaliteNB.ca

Suzanne Robichaud, RN BHSc

Is the vice-president of Primary Health Care at Vitalité Health Network

Suzanne.Robichaud@VitaliteNB.ca

Gaetane Leblanc-Cormier, RN

Is the director of Vitalité Health Network Research Centre

Gaetane.Leblanc-Cormier@VitaliteNB.ca

Susan O’Donnell, PhD

Is a senior research officer at the National Research Council of Canada and an adjunct professor at the University of New Brunswick.

Helene Fournier, PhD

Is a research officer at the National Research Council of Canada

Helene.Fournier@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Pascal Sirois, BA

Is an analyst at the National Research Council of Canada and a graduate student at the University of Moncton

pas_sdr@hotmail.com