Response and Attitudes of Undergraduate Nursing students Towards Computers in Health Care

by Poreddi Vijayalakshmi, RN,RM, BSN,MSN

Clinical Instructor, College of Nursing

& Suresh Bada Math, MD,DNB,PGDMLE

Additional Professor, Department of Psychiatry,

National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences,

(Deemed University), Bangalore. India

Author Correspondence to: Poreddi Vijayalakshmi

Email : pvijayalakshmireddy@gmail.com, vijayalakshmiporeddy@yahoo.co.in

Abstract

Background: Computer knowledge and skills are becoming essential components of technology in nursing education and practice. To date, research that examined the attitudes of nursing students who are enrolled in baccalaureate programs towards technology in healthcare is limited.

Aim: The present study was focused on the attitudes of Baccalaureate Nursing Students’ towards computers in health care.

Methodology: A descriptive study design using a quantitative approach and structured questionnaire was used to measure the nursing students’ attitudes towards computer usage. A sample of 161 BSN students participated in this study.

Results: Our findings revealed that more than three fourth of the participants (n=124, 77.0%) had realistic views of current computer capabilities and applications in health care as indicated in their responses to the questionnaire. Further, the mean score of the participants was 60.71 ±7.22 (M±SD) which indicates the participants felt comfortable in using user-friendly computer applications.

Conclusion: The findings indicate that under graduate nursing students generally held positive attitudes towards the use of computers in health care. However, students received limited computer exposure as part of their curriculum and may not be adequately prepared to work independently with computers in the workplace once they graduate. Thus, the researchers suggested integrating nursing informatics with in a leveled way throughout nursing curriculum.

Key words: Attitudes, Computers, Health care, Nursing students, P.A.T.C.H. Assessment Scale

Introduction

Over the past two decades, technology usage in nursing education has grown exponentially (Mallow & Gilje, 1999). Computers in nursing education and practice provide advanced opportunities for learning and practicing evidence-based nursing care (Samarkandi, 2011). The integration of computer technology into nursing curriculum is essential to ensure success throughout the education and future careers of contemporary nursing students (Edwards & Patricia, 2011). To this end, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing outlined introductory level nursing informatics competencies for American Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) nursing programs (AACN, 2008). Likewise, in India, the Indian Nursing Council (INC) initiated a requirement within the past seven years, outlining that all nursing students must successfully complete an introductory computer class.

Similarly, nursing students’ attitudes toward technology (ATT) may influence their successful adoption of information competencies, willingness to learn computer systems, and ultimately, the use of technology to improve patient safety (Detmer, 2005). Hence, if students have negative attitudes about the use of computers, they will perhaps avoid them and continue to learn from models with which they are familiar (Anderson, 1996; Henderson, Deane, & Ward, 1995; Loyd & Gressard, 1987). Indeed, these individuals will not benefit from the science and technology that computers offer in knowledge and skills acquisition and in delivering health care (Francisa, Katzb, & Jones, 2000). The importance of attitudes and beliefs for learning to use new technologies is widely acknowledged (DeYoung & Spence, 2004; Loyd & Gressard, 1984; Ray, Sormunen, & Harris, 1999; Saade & Galloway, 2005).

As nursing evolves into a more complex and evidence-based profession, nurses need to be proficient in computer usage and be able to communicate across a variety of healthcare-system demands. Thus, it is mandatory for nursing students to learn and acquire necessary technological knowledge and skills in a variety of settings around the globe (Bennett & Glover, 2008; Lashley, 2005). In addition, nurses will be expected to utilize computers for their personal learning and promoting quality patient care and safety (Kilbridge & Classen, 2008). Electronic Health Records allow nurses and other healthcare providers to share vital information across health systems and provide immediate access to clinical data that will reduce and eliminate medical errors, improving the efficiency of healthcare delivery, and advancing well-being for all people (Abdrbo, 2007). In the future, computers may provide additional functions related to direct patient care (Buch & Janda, 2009). Thus it is important that nursing students feel comfortable working with these health care related technologies.

A review of the literature showed that few available studies evaluated nursing students’ current level of informatics competencies (Desjardins, Cook, Jenkins, & Bakken, 2005; Elder & Koehn, 2009; Gassert, 2008; Hebda & Calderone, 2010; McDowell & Ma, 2007). As well, very few studies focused on student technology knowledge, attitudes, and skills (Cole & Kelsey, 2004; Fetter, 2009). Nonetheless, identifying the predictors of informatics competency will help to develop appropriate strategies to prepare informatics competent graduates and further yield valuable insight for informatics curriculum development (Hwang & Park, 2011). To ensure that nursing graduates are competent in the era of electronic healthcare delivery, it is essential to assess the attitudes of under graduate nursing students. To date, no documented research is available from India, related to the attitudes of nursing students towards computers in health care. Hence, the present study was focused on the assessment of Baccalaureate nursing students’ attitudes towards the use of computers in health care with a look at the factors (such as gender, age, socioeconomic status, residence) that influence these attitudes.

Methods

The study examined undergraduate Nursing students at a College of Nursing in Bangalore, India. A non-probability convenience sample was selected, and a quantitative descriptive research method was applied. Selection criteria for participants included nursing students who were studying in their second, third or fourth year of the nursing program and were willing to participate. There were no exclusion criteria apart from a lack of willingness to participate. One hundred-seventy students were enrolled in the study. However, nine questionnaires were discarded due to incomplete data. Hence, 161 completed questionnaires were analyzed for this study.

Instruments

Demographic Data Survey Instrument

The demographic data form consisted of five items selected to elicit data about the background of the participants in the study including age, education, monthly family income, and residence.

P.A.T.C.H. Assessment Scale v. 3 – Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare

The P.A.T.C.H. Assessment Scale v. 3 – Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare © developed by June Kaminski (v.1- 1996, v.2 – 2007, v.3 – 2011) was used to assess the students’ attitudes. This scale is a valid and reliable, self- report measure of attitudes towards computers in health care. In this study, the scale was administered to students along with a brief demographic form.

The P.A.T.C.H. tool has 50 items (25 items are negatively worded) that measure attitudes toward computers in health care. Respondents were given the choice of five likert scale response categories to choose from, based on their feelings: ranging from agree strongly to disagree strongly (agree strongly = 2, agree = 1.5, not certain = 1, disagree = 0.5, disagree strongly = 0) accordingly. The total score ranges between 0 – 100.

The score interpretation results are:

- 0 – 17 indicates signs of cyberphobia,

- 18 – 34 indicates the user is unsure of the usefulness of computers in health care,

- 35 -52 indicates limited awareness of the applications of computer technology in health care,

- 53 – 69 indicates the user has a realistic view of current computer capabilities in health care,

- 70 – 86 indicates the user has an enthusiastic view of the potential of computer use in health care and

- 87 – 100 indicates a very positive view of computer use in health care.

The test-retest reliability of items of Pretest for Attitudes toward Computers in Healthcare Assessment Scale was 0.20 – 0.77, and 0.85 for the total scale. For internal consistency, the Scale item total correlation was 0.06 – 0.68 and Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.92. Concurrent validity was examined through a correlation between the Attitudes toward Computers Scale and the P.A.T.C.H. – Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare Assessment Scale scores with positively significant correlated results (r=0.66, p<0.01) (Kaya & Turkinaz, 2008).

Procedure

The demographic data tool and the P.A.T.C.H. Scale were distributed to each batch of students in a group setting using a common meeting place such as a lecture hall. To introduce the study, a verbal explanation of the research aims and methods was provided by the researcher (primary author) to all participants. Those who consented to participate formed our final sample. It was explicitly explained to the students that their responses would have no influence on their semester exams. The participants could complete both questionnaires in about 30-40 minutes.

Permission was obtained from the administrators of the college where the study was conducted. Participants were introduced to the aims and procedures of the study to decide if they would like to participate. After they agreed to participate verbally, the researcher gave them the confidential questionnaire. Data collection tools contained no identifying information and therefore kept the individual responses confidential.

Statistical analysis

Responses of the negatively worded items were reversed before data analysis. The data were analyzed using appropriate statistics and results were presented in narratives and tables. Descriptive (frequency and percentage) and inferential statistics (Chi-square test) was used to interpret the data. The results were considered statistically significant if the p value was < 0.05.

Results

The sample of the present study was comprised of a total of 161 nursing students and was predominantly female (n=154, 95.7%). The mean age of the participants was 18.6 ± 1.03 (M±SD) and average income was (in thousands) Rs/- 1.17± 1.24 (M±SD). The majority (n=131, 81.4%) of the participants belonged to the Christian community and more than half (52.2%) of the participants were from a rural background.

The sample of the present study was comprised of a total of 161 nursing students and was predominantly female (n=154, 95.7%). The mean age of the participants was 18.6 ± 1.03 (M±SD) and average income was (in thousands) Rs/- 1.17± 1.24 (M±SD). The majority (n=131, 81.4%) of the participants belonged to the Christian community and more than half (52.2%) of the participants were from a rural background.

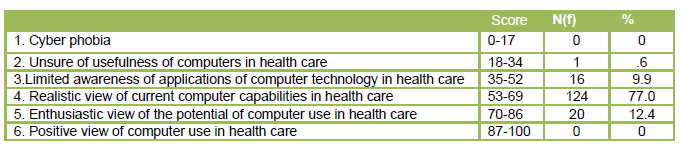

Table 1 shows the responses of the participants to the P.A.T.C.H. – Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare scale. Only one participant (0.6%) was unsure of the usefulness of computer technology in health care. Very few of the participants (n=16, 9.9%) showed limited awareness of the applications of computer technology in health care with a total score of 35-52. More than three quarters of the participants (n=124, 77.0%) had realistic views of the current computer capabilities in health care. A small number of the participants (n=20, 12.4%) had enthusiastic views of the potential of computer use in health care. None of the participants had very positive view of computer use in health care (scores of 87 to 100).

Table 1. Responses of the participants to the P.A.T.C.H. – Pretest for Attitudes toward Computers in Healthcare scale (N=161)

However, the mean score of the responses was 60.71 ±7.22 (M±SD) which indicates the participants felt moderately comfortable in using user-friendly computer applications, and had a realistic view of how computers are currently used in healthcare. The findings of association showed that the levels of attitude were not associated with gender, religion or background of the nursing students.

Discussion

This was the first innovative study from India that assessed Baccalaureate nursing students’ attitudes towards computers in health care. Very few studies examined nursing students’ attitudes towards computers overall. The studies that did exist focused on gender differences (Samarkandi, 2011), evaluation of computer curriculum in BSN programs (Ornes & Gassert, 2007) and students anxiety related to computer literacy (Akhu-Zaheya, Khater, Nasar, & Khraisat, 2011). Nonetheless the current study took a very cursory look at the issue of students’ attitudes towards computers in health care. The findings are expected to be beneficial to nurse administrators, and for nursing faculty to assess nursing attitudes towards computers in health care. However, like previous studies, the present study confirmed that nursing students primarily had moderately positive attitudes towards the usage of computer technology in nursing practice.

The sample in the present study was predominantly female between the ages of 17 to 22 years old. Studies have shown that student age affects computer – related attitudes. Parallel to findings of previous studies (Krendl & Broihier, 1992), youth was identified as an important factor for student attitudes toward computers. It was reported that younger students enjoyed working with computers more than older students. They were also more confident and enthusiastic about computer use compared to their older counterparts. Contrary to these findings, another study found that computer attitudes are modifiable for people of any age group (Czaja & Sharit, 1998).

Although, in the present study, more than three quarters of the participants (n=124, 77.0%) had realistic views of current computer capabilities in health care, only 12.4% (n=20) had enthusiastic views of the potential of computer use in health care and none of the participants had very positive views. These findings could be partially due to the fact that the participants had completed basic computer courses (15 hours of theory and 30 hours of practical experience) during their first year of their program. This practice was incorporated to meet the Indian Nursing council computer literacy standards that mandated this type of knowledge and practice for all undergraduate nursing students.

Previous research found that students’ level of confidence with technology has increased as a result of practice and experience (Krendl & Broihier, 1992; Pope-Davis & Vispoel, 1993). These finding suggest that taking a formal course in computer technology is a useful approach to introducing the computer to students and it is also an effective method for reinforcing and strengthening computer knowledge and skills. As well, establishing a baseline of informatics competencies in undergraduate nursing students is vital to planning informatics curricula and adequately preparing students to promote safe, evidence-based nursing care (Hebda & Calderone, 2010).

In a previous study (Dyck & Smither, 1994) it was found that higher levels of experience were associated with more positive attitudes toward computers. Further, it was observed that baccalaureate nursing students are competent (Desjardins, et al., 2005) or have moderate informatics and technology knowledge, attitudes, and skills (Fetter, 2009; McDowell & Ma, 2007). These researchers’ findings are similar to the results that were reported in the current study. The mean score of the participants in the present study was 60.71 ±7.22 (M±SD) which indicates the participants felt comfortable using user-friendly computer applications. Consequently, if students have negative attitudes about the use of computers, they will perhaps avoid and resist using them, preferring to learn from less technical models with which they are familiar (Anderson, 1996; Henderson, et al., 1995).

Indeed, these students will not benefit from the science and technology that computers offer in knowledge and skills acquisition and in delivering health care (Francisa, et al., 2000). Furthermore, in a recent survey nurse administrators anticipated that nurses who are enriched with computer literacy are better able to utilize the information technology that enhances patient care (Reiss, 2006). Besides, health care educators and nurse administrators know that nurses should be competent and strengthen their computer skills to enhance their knowledge and contribute to the success of their academic learning and skill achievement (Maag, 2006).

Based on the results of this study, age, religion and background did not influence student attitudes toward the use of computers in healthcare. The majority of respondents felt comfortable and held realistic views of the place and merit of computers in nursing practice. The literature supports this, and suggested integration of informatics throughout the nursing curriculum with increasing levels of complexity to prepare students for the reality of contemporary nursing practice (Flood, Gasiewicz, & Delpier, 2010). Two studies of nurse executives and deans and directors of undergraduate and graduate programs also recommended that new graduate nurses needed to be familiar with nursing-specific software such as computerized medication-administration systems(McCannon & ONeal, 2003) and recommended improving incorporation of these skills into nursing curricula (McNeil et al., 2003). The students in this study did receive a basic introduction to computers before this study.

Limitations

The present study is not without its limitations: the study would be strengthened by increasing the sample size and examining gender differences. It might be interesting to include students’ self efficacy and previous exposure to computers during their secondary education as independent variables to further examine the effect on students’ attitudes toward computers in health care.

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that undergraduate nursing students have realistic and generally positive attitudes towards computers in health care. Nurse educators need to be cognizant of how to create favorable learning environments to foster positive attitudes towards the use of computers in health care. Most students receive limited computer exposure as part of their nursing education and may not be adequately prepared for the future technological requirements of practice. Thus, the researchers suggest that nursing programs integrate nursing-specific software within BSN curriculum to help beginning nurses to work efficiently in an environment that increasingly relies on information technology to promote patient safety.

References

AACN. (2008). American Association of College of Nursing:The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice.

Abdrbo, A. (2007). Factors affecting information systems use and its benefits and satisfaction among Ohio registered nurses (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, Ohio).

Ajuwon, G. A. (2003). Computer and internet use by first year clinical and nursing students in a Nigerian teaching hospital. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 3(10), 231-236.

Akhu-Zaheya, L. M., Khater, W., Nasar, M., & Khraisat, O. (2011). Baccalaureate nursing students’ anxiety related computer literacy: a sample from Jordan. Journal of Research in Nursing (In press).

Alsebail, A. (2004). The College of Education students’ attitudes toward computers at King Saud University (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ohio University).

Anderson, A. (1996). Predictors of computer anxiety and performance in information system. Computer in Human Behavior, 12(1), 67-77.

Ayoub, L. J., Vanderboom, C., Knight, M., Walsh, K., Briggs, R., & Grekin, K. (1999). A study of the effectiveness of an interactive computer classroom. Computers in Nursing,, 16(6), 333-338.

Bennett, P., & Glover, P. (2008). Video streaming: Implementation and evaluation in an undergraduate nursing program. Nurse Education Today, 28, 253-258.

Buch, B., & Janda, M. (2009). The challenges of clinical validation of emerging technologies: Computer-assisted devices for surgery. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 91, 17-21.

Chin, K. (2001). Attitudes of Taiwanese nontraditional commercial institute students toward computers (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of South Dakota, Vermillion).

Cole, I., & Kelsey, A. (2004). Computer and information literacy in post-qualifying education. Nurse Education in Practice, 4(3), 190-199.

Czaja, S. J., & Sharit, J. (1998). Age differences in attitudes toward computers. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(5), 329-340.

Desjardins, K., Cook, S., Jenkins, M., & Bakken, S. (2005). Effect of an informatics for evidence-based practice curriculum on nursing informatics competencies. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 74(11-12), 1012-1020.

Detmer, D. E. (2005). Making learning a core part of healthcare information technology. Paper presented at: MedBiquitious Conference. April 6, 2005; Baltimore, Md. Retrieved from: http://medbig. erg/events/conferences/annual conference/2005/presentations. htm. August 20, 2005.

DeYoung, C. G., & Spence, I. (2004). Profiling information technology users: enroute to dynamic personalization. Computers in Human Behavior, 20, 55-65.

Dyck, J. L., & Smither, J. A. (1994). Age differences in computer anxiety: The role of computer experience, gender and education. Journal of Educational Computing Research Research,, 10(3), 239-248.

Edwards, J., & Patricia, A. O. C. (2011). Improving Technological Competency in Nursing Students:Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing. The Journal of Educators Online, 8(2).

Elder, B. L., & Koehn, M. L. (2009). Assessment tool for nursing student computer competencies. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(3), 148-152.

Fetter, M. S. (2009). Graduating nurses’ self-evaluation of information technology competencies. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(2), 86-90.

Flood, L. S., Gasiewicz, N., & Delpier, T. (2010). Integrating information literacy across a BSN curriculum. Journal of Nursing Education, 49 (2), 101-104.

Francisa, L., Katzb, Y., & Jones, H. (2000). The reliability and validity of the Hebrew version of the Computer Attitude Scale. Computers & Education, 35, 149-159.

Gassert, C. A. (2008). Technology and informatics competencies. Nursing Clinics of North America, 43(4), 507-521.

Hebda, T., & Calderone, T. (2010). What nurse educators need to know about the TIGER initiative. Nurse Educator, 35(2), 56-60.

Henderson, R. D., Deane, F. P., & Ward, M. J. (1995). Occupational differences in computer-related anxiety: Implications for the implementation of a computerized patient management information system. Behavior and Information Technology, 14(1), 23-31.

Hwang, J. I., & Park, H. A. (2011). Factors associated with nurses’ informatics competency. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 29(4), 256-262.

Kaminski, J. (1996, 2007, 2011). Pretest for Attitudes Toward Computers in Healthcare: P.A.T.C.H. Assessment Scale v. 3. Retrieved from http://nursing-informatics.com/niassess/plan.html. Nov 10th 2012.

Kaya, N., & Turkinaz, A. (2008). Validity and Reliability of Turkish version of the Pretest for Attitudes towards Computers in Healthcare Assessment Scale. Journal of Istanbul University Florence Nightingale School of Nursing, 16(61), 24 – 32.

Kilbridge, P., & Classen, D. (2008). The informatics opportunities at the intersection of patient safety and clinical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 15(4), 397-407.

Krendl, K. A., & Broihier, M. (1992). Student responses to computers: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 8(2), 215-227.

Lashley, M. (2005). Teaching health assessment in the virtual classroom. Journal of Nursing Education, 44(8), 348-350.

Loyd, B. H., & Gressard, C. (1984). Reliability and factorial validity of computer attitude scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 44, 501-505.

Loyd, B. H., & Gressard, C. P. (1987). Gender and computer experience of teachers as a factors in computer attitudes of middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 7(1), 13-19.

Maag, M. (2006). Nursing students’ attitudes toward technology: A national study. Nurse Educator, 31(3), 112-118.

Mallow, G. E., & Gilje, F. (1999). Technology-based nursing education: overview and call for further dialogue. Journal of Nursing Education, 38(6), 248-251.

McCannon, M., & ONeal, P. V. (2003). Results of a national survey indicating information technology skills needed by nurses at time of entry into the work force. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(8), 337-340.

McDowell, D., & Ma, X. (2007). Computer literacy in baccalaureate nursing students during the last 8 years. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 25(1), 30-36.

McNeil, B., Elfrink, V., Bickford, C., Pierce, S., Beyea, S., & Averill, C. (2003). Nursing information technology knowledge, skills, and preparation of student nurses, nursing faculty, and clinicians: A U.S. survey. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(8), 341-349.

Ornes, L. L., & Gassert, C. (2007). Computer competencies in a BSN program. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(2), 75-78.

Pope-Davis, D. B., & Vispoel, W. P. (1993). How instruction influences attitudes of college men and women towards computers. Computer in Human Behavior, 9, 83-93.

Ray, C. M., Sormunen, C., & Harris, T. M. (1999). Men’s and Women’s Attitudes Toward Computer Technology: A Comparison. Office Systems Research Journal, 17(1), 1-8.

Reiss, S. (2006). Leadership styles and brain dominance in lead nurses: An educational management tool (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK).

Saade, R. G., & Galloway, I. (2005). Understanding Intention to Use Multimedia Information Systems for Learning. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 287-295.

Samarkandi, O. A. (2011). Students’ Attitudes Toward Computers at the College of Nursing at King Saud University (KSU). Doctor of Philosophy, Case Westeren Reserve University