Informatics in Nursing Leadership: Leading in the Age of Technology

Andrea Knox, RN, BSN, CON(c)

Senior Practice Leader – Kelowna

BC Cancer Professional Practice Nursing

Abstract

Nursing leaders require a variety of unique skills, including informatics, to support the delivery of safe and effective patient care (Dyess, Sherman, Pratt, Chiang-Hanisko, 2016; Leach & McFarland, 2014; Ritchie & Blair, 2017; Saul, Best, & Noel, 2014; Solman 2017). The Canadian Nurses Association and Canadian Nurses Informatics Association joint position statement on nursing informatics (Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017) holds it is essential for all nurses to develop informatics competencies. However there is a notable absence of verbiage specific to the development of informatics skills in nurse leaders (Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017). The purpose of this narrative review is to explore informatics competencies in relation to nursing leadership and provide a synthesis of the available literature regarding current recommendations and implications for competency development. Key recommendations identified include “Nursing Leadership’s Role in Healthcare Informatics, Nursing Leadership in Healthcare Informatics Drives Interoperability, Nursing Leaders Need Big Data, and Nursing Leadership Informatics Competency Development”. Nursing leaders need to develop informatics competencies to drive professional interoperability, ensure nursing data is leveraged to inform decision making, and provide patients with efficient, safe and innovative care.

Keywords: Nursing, leadership, informatics, competencies

Introduction

Strong leadership in nursing requires developing a plethora of skills encompassing clinical knowledge, interpersonal communication, systems thinking, adaptability, collaboration, quality assurance, and human resource management (Dyess, Sherman, Pratt, & Chiang-Hanisko, 2016; Leach & McFarland, 2014). Nurses who move into leadership positions may find themselves accountable for workforce planning, data analytics, metrics reporting, operational budgets and project management; all while fostering shared accountability with front line staff for the delivery of safe and effective patient care (Leach & McFarland, 2014; Ritchie & Blair, 2017; Saul, Best & Noel, 2014; Solman, 2017). Interwoven through each of those factors is the continuous influx of emerging technologies intended to promote system efficiencies, support timely and relevant access to information, and enhance the accuracy and safety of care delivery (Solman, 2017). As a result, nursing leaders are required to merge their own idealistic expectations of being a strong leader with the challenges of a practice environment in a constant state of technological evolution (Dyess, et al., 2016).

This technological evolution encompasses a wide variety of information and communication technologies (ICTs) such as email communication between members of the health care team, deployment of new bedside monitoring equipment, or the design and implementation of a new electronic health record (EHR) (Canadian Nurses Association, 2006; Canadian Nurses Association, 2015;Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017).With the increasing presence of technology in health care, the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) and Canadian Nurses Informatics Association (CNIA) developed a joint position statement on nursing informatics (Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017). Within the joint statement nursing informatics was defined as a science and practice that “integrates nursing, its information and knowledge, and their management with information and communication technologies to promote the health of people, families and communities world-wide” (Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017, p.1).

Background

Prior to the release of CNA’s “E-Nursing Strategy for Canada” in 2006, formal work on integrating nursing informatics content into nursing curricula was lacking (Canadian Nurses Association, 2006). Even with the identification of the national strategy in 2006 to guide nursing forward with technology (Canadian Nurses Association, 2006), a formal competency framework was absent in Canada until the release of the nursing informatics entry to practice competencies in 2015 (Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing, 2015). While the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN) informatics competencies were a key step forward in supporting skill development at the undergraduate level (Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing, 2015), a gap remained for advancing the skill and knowledge for nursing leaders already entrenched on the front lines of change. While CNA and CNIA’s position holds that it is essential for all nurses to develop informatics competencies in order to function within the complexity of the health care environment, there is a notable absence of verbiage specific to the development of informatics skills in nurse leaders (Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017).This deficient linkage between informatics and leadership in the CNA-CNIA document can be interpreted as direction for the development of skills in front-line staff who interact with emerging technologies daily for the purpose of direct patient care (Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017).

Yet nursing leaders also interact with technology daily for different reasons such as coordinating the delivery of services, participating in systems-level planning for implementation of new technology, and accessing systems for quality assurance data that drives decision-making (Leach & McFarland, 2014; Ritchie & Blair, 2017; Solman, 2017). While adept at utilizing ICT’s for the purpose of routine tasks, when it comes to the intricacies of understanding and leveraging technology behind the scenes of care, nursing leaders will often defer to Information Technology (IT) personnel or product vendors (Simpson, 2010). With such experts available to nursing leaders the question arises: “What are the current recommendations and implications for the development of informatics competencies in nurse leaders?”. As such, it is the purpose of this narrative review to explore informatics competencies in relation to nursing leadership and provide a synthesis of the available literature to address the question at hand.

Methods

To support this narrative review of the literature for the purpose of addressing the question posed, the Ovid, CINAHL and PubMed databases were searched using the MeSH terms “nursing leaders AND informatics”. A brief search of the Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER) website was also conducted for literature related to the previously identified search terms. This website was selected for inclusion in the search strategy as it is a well-known initiative in the field of nursing informatics. The literature search inclusion criteria were limited to full text, peer reviewed articles, available in English that were published between 2013 and 2018. It is noted that the limits placed on the literature search, such as English only with full text, may have inadvertently excluded some relevant published works. However, the time and cost associated with translation of non-English articles was beyond the scope of this narrative review. It must also be noted that the exclusion of literature prior to 2013 may have removed earlier published works relevant to the question posed. However, the inclusion time frame was selected based on its alignment with the development of the CASN entry to practice competencies; the intention being to review the literature on leadership and informatics published in parallel to the key documents published by CASN, CNA, and CNIA (Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing, 2015; Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association, 2017; Nagle et. al, 2014).

Results

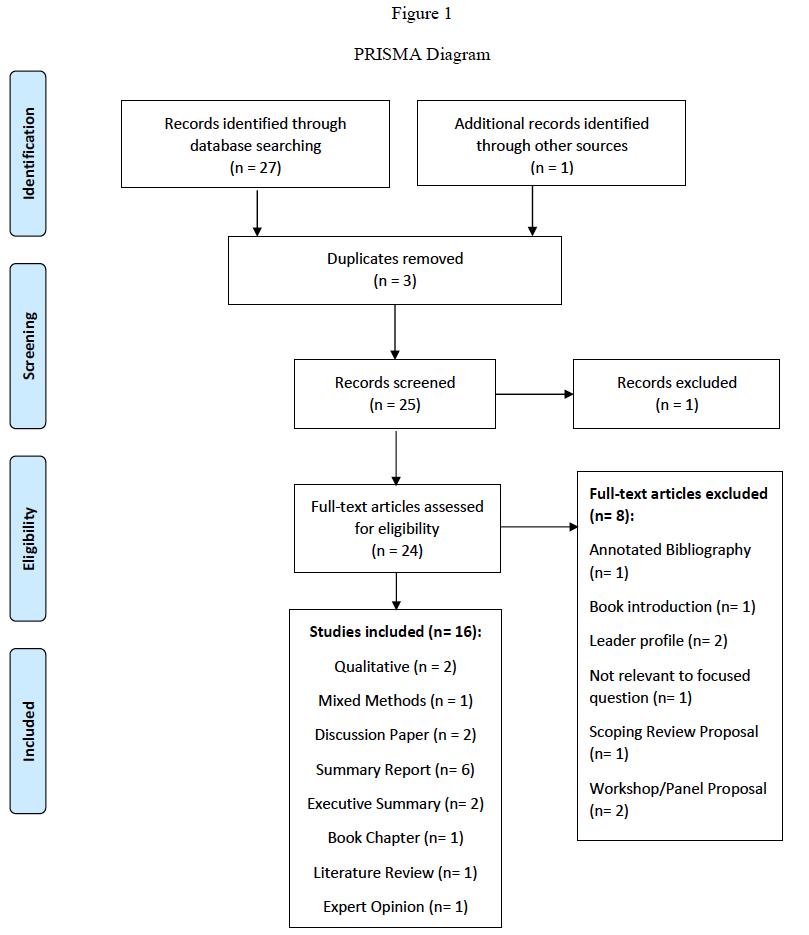

The database and manual literature searches resulted in the identification of 28 articles for preliminary screening, which was reduced to 25 after the removal of three duplicates. Initial screening by title and abstract review resulted in the exclusion of one article. A full-text review was then completed to screen the remaining 24 articles for relevancy to the question posed. This resulted in the exclusion of an additional eight articles that were found to lack relevance to the question, were presented as an annotated bibliography or book introduction, delineated a proposal to complete a scoping review and biographical profiles of leaders in the field of nursing informatics. A PRISMA diagram was formed (Figure 1) to provide a visual map of the identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion/exclusion process. Sixteen eligible articles were identified for inclusion comprising a mix of qualitative or mixed method research designs, discussion papers, summary reports, opinion pieces and literature reviews. A data extraction table was created as part of the data synthesis process to summarize the key findings from each article (Appendix A). As only three of the articles reviewed represented formal research on informatics competencies and nursing leadership, a mix of empirical studies and theoretical papers were included to provide a representative overview of the current evidence.

Quality Assessment

The mixed method (Collins, Yen, Phillips, & Kennedy, 2017) and qualitative studies (Simpson, 2013; Staggers, Elias, Makar & Alexander, 2018) were evaluated using either the overview of the Delphi method provided by Okoli & Pawlowksi (2004) or the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (Tong, Sainsbury & Craig, 2007) respectively as guides for a quality assessment. For the qualitative studies, both were published in peer reviewed journals and outlined a clear data collection and analysis process with a high degree of reflexivity apparent (Simpson, 2013; Staggers et al., 2018). Neither study identified a paradigmatic underpinning, however Simpson (2013) clearly acknowledged the use of an ethnographic methodology for the research design. As a result, it was not possible to fully determine methodological congruency; though consistency in approach was noted in the aspects of research design presented by the authors. Sample sizes for the qualitative studies ranged from 7 – 27 using a purposive sampling of nursing leaders in informatics related roles, representing an appropriate cross section of relevant participants for a qualitative research approach on the topic in question.

The mixed method study by Collins et al. (2017) incorporated an environmental scan with a purposive sample of nursing informatics leaders across three Delphi rounds with response rates ranging from 26 – 41. According to Okoli & Pawlowski (2004) the Delphi method is considered a “stronger methodology for a rigorous query of experts and stakeholders” than a traditional survey (p. 18). In comparing the Delphi method employed in the recommendations for design by Okoli & Pawlowski (2004) there is methodological congruency present in the Collins et al. (2017) study. Overall, quality criteria for the formal research studies revealed a moderate rating for the qualitative and mixed method grouping (Collins et al., 2017; Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004; Simpson, 2013; Staggers et al., 2018; Tong, Sainsbury & Craig, 2007).

The remaining 13 articles reviewed comprised a mix of discussion papers (Hussey, Adams & Shaffer, 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2015), summary reports (Hartley, 2014; Honey & Westbrooke, 2016; Kerfoot, 2015; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER), 2014; Troseth, 2014; Weaver & O’Brien, 2016; Westra et. al, 2015), an opinion piece (Strudwick, 2016), a book chapter (Phillips, Yen, Kennedy & Collins, 2017) and a literature review (Remus, 2016). To assess the non-research articles for quality, the evidence appraisal tool developed by Johns Hopkins Nursing presented in Buccheri & Sharifi’s (2017) overview of critical appraisal tools was used as a guide. All the articles aligned with Level V on the Johns Hopkins evidence appraisal tool and consistently met the criteria within to be identified as good quality given the inclusion of relevant and current literature, expert resources, meaningful analysis, and consistent recommendations.

Findings

In considering the recommendations and implications for development of informatics competencies in nurse leaders, the literature identified for inclusion was studied to formulate a summary of the current evidence using a narrative review approach (Green, Johnson & Adams, 2006; Mays, Pope & Popay, 2005). The selection of a narrative review approach is appropriate given the flexibility and comprehensiveness it allows when synthesising the evidence presented in a mix of research and non-research articles. The review of the identified literature resulted in the formulation of four overarching themes:

- Nursing Leadership’s Role in Healthcare Informatics

- Nursing Leadership in Healthcare Informatics Drives Interoperability

- Nursing Leaders Need Big Data

- Nursing Leadership Informatics Competency Development

Nursing Leadership’s Role in Healthcare Informatics

The role of the nursing leader encompasses clinical and managerial responsibilities that may vary depending on clinical setting or placement in the organizational hierarchy. In looking at nursing leadership literature through the context of informatics, it is apparent that leaders are pivotal to technology integration in every arena of nursing practice (Honey & Westbrooke, 2016; Hussey, Adams & Shaffer, 2015; Kerfoot, 2015; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). Healthcare’s continuous state of transformation now requires nurse leaders to develop informatics skills and competencies; it is no longer optional if one wants to lead effectively in the technological age (Collins et al., 2017; Honey & Westbrooke, 2016; Hussey & Kennedy, 2015; Hussey, Adams & Shaffer, 2015; Kerfoot, 2015; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Phillips et al., 2017; Remus, 2016; Simpson, 2013; Staggers et al., 2018; Strudwick, 2016; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Troseth, 2014). Nursing leaders who develop informatics competencies can work more effectively in ensuring the “successful selection, development, and competent use of devices and clinical systems” (Kerfoot, 2015, p 342). Additionally, nurse leaders with informatics competencies and knowledge will be needed at higher levels to inform policy and decision making related to ICT implementation (Honey & Westbrooke, 2016; Hussey et al., 2015; Simpson, 2013; Strudwick, 2016; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014).

Given their clinical background, nurse leaders are also positioned to provide a holistic perspective when organizations move to develop integrated models of care that leverage technology, such as telehealth, to transform patient care delivery (Hussey et al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Simpson, 2013; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). The intertwining of technology and nursing practice creates an interdependency that, when leveraged properly by nursing leaders, can create project synergy and bolster their ability to advocate for ICT solutions that meet patient needs and yield sustainable quality patient outcomes (Honey & Westbrooke, 2016; Hussey & Kennedy, 2015; Hussey et al., 2015; Remus, 2016; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Troseth, 2014). To put it simply, leaders who develop and adopt informatics competencies can help bridge the gap between clinical nursing practice and IT (Hussey et al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Simpson, 2013; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014).

Nursing Leadership in Healthcare Informatics Drives Interoperability

While the use of ICTs has become more widespread and new models of care emerge that capitalize on technological advancements, nurses continue to have usability issues related to ICTs in practice (Staggers et al., 2018). Common issues reported include EHR designs that do not support how nurses document or interact with patient information, computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems that do not account for nursing activities, or lack of interfaces with biomedical devices and other patient data collection systems (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Staggers et al,. 2018; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). For nurses this could translate into challenges with electronic documentation in the EHR, delays in care if physicians are required to enter nursing orders, or the need to access multiple systems for information to develop a comprehensive understanding of the patient picture (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Staggers et al., 2018; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). Ultimately, lack of consideration for nursing workflows during planning and design can result in a fragmented system that functions contrary to the TIGER recommendation for professional interoperability- the sharing of expertise and knowledge across disciplines in a meaningful and transparent way (Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). According to Staggers et al. (2018) this “means nurses become the human interface and integrator among disparate systems” (p 192). As such, nurse leaders need to develop a deeper understanding of nursing informatics and merge it with their clinical knowledge to effectively inform, influence or lead technology related initiatives that impact nursing workflow at the point of care (Hussey et al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Kerfoot, 2015; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Simpson, 2013; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014).

Nursing Leaders Need Big Data

Big data in health informatics can be defined as “the field of information management and interpretation on data whose scale, diversity and complexity require new design techniques to extract hidden knowledge” (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016, p 1032). Nursing leaders need to be aware of and skilled at using big data to advance nursing practice (Kerfoot, 2015; Westra et. al, 2015; Strudwick, 2016). Currently nursing is considered the single largest user of health informatics technology, yet the profession receives little information back that can be used to inform practice (Weaver & O’Brien, 2016). Further, data input by nurses is not currently linked to other real-time knowledge or context; limiting data interpretation or ability to quantify nursing care in a meaningful way (Weaver & O’Brien, 2016). In a sense, the nursing profession finds itself at the mercy of the “DRIP”- nurses are “data rich and information poor” (Weaver & O’Brien, 2016; Westra et. al, 2015, p 306). Westra et. al (2015) highlighted that data collection and analysis are the foundation to knowledge creation. For nursing, the utilization of data provides an opportunity to generate a deeper understanding of the impact of nursing care (Kerfoot, 2015; Westra et. al, 2015). Nursing leaders with informatics expertise can leverage data to identify patterns and correlations in the delivery of nursing care, potentially identifying areas to target for quality improvement (Kerfoot, 2015; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Weaver & O’Brien, 2016; Westra et. al, 2015).

A consistent recommendation was noted across the literature for nursing leaders to advocate for the use of standardized clinical data sets, such as the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine — Clinical Terms(SNOMED CT) or the Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes(LOINC), to capture and enhance the utilization of nursing data in electronic health records (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Weaver & O’Brien, 2016; Westra et. al, 2015). One example specific to nursing is the Canadian Health Outcomes for Better Information and Care (C-HOBIC) standardized data set (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016). The C-HOBIC data set is designed for use across the domains of home care, acute care, long-term care and complex care nursing practice settings (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016). C-HOBIC can provide nursing leaders with the pragmatic ability to leverage clinical data from admission and discharge for the purpose of assessing the quality of care delivery, informing innovative health systems design, and driving policy development in health care (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Kerfoot, 2015; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Strudwick, 2016; Westra et. al, 2015).

Nursing Leadership Informatics Competency Development

The current literature clearly demonstrates there is a definitive role for the nursing leader that demands the development of informatics knowledge and skills to advance nursing practice and transform healthcare (Honey & Westbrooke, 2016; Hussey et al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Kerfoot, 2015; Staggers et al., 2018; Strudwick, 2016; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Weaver & O’Brien, 2016; Westra et. al, 2015). There is a gap, however, between the informatics skills required of nursing leaders and the availability of formal training and education to develop informatics competencies (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Kerfoot, 2015). The findings reported by Collins et. al., (2017) revealed that nurse leaders described developing informatics competencies as a result of “on-the-job” (p. 215) training. The lack of formalized training was broadly seen by study participants as inadequate to meet their skill development needs as leaders and could result in a continued marginalization of nursing if the profession is limited in starting “informed discourse in technology dependent healthcare environments” (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016, p. 1032). There was a consensus recommendation across the literature for informatics education at the master’s or doctoral level to support skill level development in graduates assuming leadership roles (Hussey et al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Simpson, 2013). Health informatics knowledge should no longer be delegated to others but should be an expected core competency in nursing practice at all levels (Collins et. al., 2017).

Similar consensus was apparent across the literature concerning the specific informatics competencies nurse leaders should acquire. Recommended competencies for leaders included knowledge of legal and ethical issues related to the use of ICTs, use of technology in accordance with professional standards, and the ability to generate discussions on the motives for technology implementations from a nursing lens (Collins et. al., 2017; Hussey, et al., 2015; Simpson, 2013; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). The abilities of modeling, analyzing and formalizing nursing knowledge for clinical practice, research, education and management related to ICTs were also identified (Collins et. al., 2017; Hussey, et al., 2015; Simpson, 2013; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). Collins et al.’s (2017) Delphi study identified 108 informatics initial competency items which were reduced to 74 by the end of the Delphi rounds. The top 15 competencies were then ranked by the priority assigned by study participants and demonstrated a shifting focus to new leadership competencies focused on outcomes, cost and quality. The abilities of advocating for the development of cost effective, integrated systems and to inform strategic planning and decision making through the leveraging of ICT data were identified as examples of emerging informatics competencies for leaders (Collins et al., 2017). Collins et al., (2017) also identified a need for the development and use of a validated tool for nurse leaders to assist with self-assessment of informatics competency and support planning for attainment of the required skillset. Phillips et al., (2017) also highlighted the importance of baseline informatics competencies in nursing leaders to assist with the advancement of nursing practice at pace with technology. The incorporation of a validated competency self-assessment tool in the nurse leader’s orientation can provide a sustainable path to improve informatics competencies over time (Phillips et al., 2017).

Recommendations

The purpose of this narrative review was to explore and synthesize the literature while addressing the question “What are the current recommendations and implications for the development of informatics competencies in nurse leaders?”. Four main themes were identified concerning the nurse leader’s role in informatics, interoperability, big data and competency development. Under the theme of nursing leadership’s role in healthcare informatics, it was identified that informatics competency development is recommended to support effective leadership in todays healthcare environments (Collins et al., 2015; Kerfoot, 2015; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Phillips et al., 2017; Remus, 2016; Simpson, 2013; Staggers et al., 2018; Strudwick, 2016; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Troseth, 2014). Nursing leaders who develop and adopt informatics competencies are needed to inform policy and decision making by bridging the gap between IT and clinical practice (Honey & Westbrooke, 2016; Hussey et. al., 2015; Simpson, 2013; Strudwick, 2016; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014).

If leaders fail to develop informatics skills and integrate them with their clinical knowledge, the impact will be felt at the point of care with the implementation of fragmented systems that misalign with nursing workflows (Hussey et. al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Kerfoot, 2015; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Simpson, 2013; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014). The second recommendation surmised from this review is for nursing leaders to engage with informatics to drive professional interoperability; ensuring appropriate and meaningful use of technology across the health care spectrum.

The third theme centered on the concept of big data, and it is recommended that nursing leaders leverage available data for quality improvement. Developing informatics competencies can help nurse leaders to identify patterns and correlations in the delivery of nursing care, valuable information that can inform decision making and quantify the impact of nursing care (Kerfoot, 2015; Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Weaver & O’Brien, 2016; Westra et. al., 2015). It is recommended that leaders advocate for the use of standardized clinical sets, such as C-HOBIC (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016), to support the capture of nursing specific data in electronic health records (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016;Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform, 2014; Weaver & O’Brien, 2016; Westra et. al., 2015).

The final theme identified in the literature review encompassed informatics competency development for nursing leaders. There was consensus that informatics should be a core competency for nursing at all levels of practice, not something to be deferred to IT experts or product vendors (Collins et. al., 2017; Hussey et. al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Simpson, 2013). To identify learning needs, it is recommended that nursing leaders utilize a validated informatics competency self-assessment tool (Collins et. al., 2017; Phillips et. al., 2017). Once learning needs are identified, attainment of informatics knowledge and skills through education at the master’s or doctoral level is recommended for nursing leaders (Collins et. al., 2017; Hussey et. al., 2015; Hussey & Kennedy, 2016; Lloyd & Ferguson, 2017; Simpson, 2013). Nursing leaders must drive the conversation and awareness of the importance of informatics skill development in all nurses to ensure continued engagement and presence of voice as the technology evolution marches forward (Hussey & Kennedy, 2016).

Limitations

Limitations of this narrative review can be derived from the literature selected for inclusion. There is a notable lack of formal research in the area of nursing informatics as it relates to leadership, resulting in most articles reviewed to be of the non-research variety. While quality assessment of all the articles included was thorough and revealed a rating of moderate and good quality for the empirical and theoretical articles respectively, further formal research is recommended. Additionally, the limitations utilized in the literature search strategy concerning language and timeframe may have inadvertently removed publications relevant to this narrative synthesis. A full critical review of the literature is recommended to provide a more detailed examination of the themes related to nursing leadership and informatics.

Conclusion

Nursing leaders require a variety of unique skills, including informatics, to support the delivery of safe and effective patient care (Dyess et al., 2016; Leach & McFarland, 2014; Ritchie & Blair, 2017; Saul et al., 2014; Solman, 2017). This review identified key recommendations for nursing leaders from four main themes noted in the literature; “Nursing Leadership’s Role in Healthcare Informatics, Nursing Leadership in Healthcare Informatics Drives Interoperability, Nursing Leaders Need Big Data, and Nursing Leadership Informatics Competency Development”. Nursing leaders need to develop informatics competencies to drive professional interoperability, ensure nursing data is leveraged to inform decision making, and provide patients with efficient, safe and innovative care. The future is now, let’s embrace it!

Appendix A

References

Buccheri, R., Sharifi, C. (2017). Critical Appraisal Tools and Reporting Guidelines for Evidence-Based Practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(6), 463-472.

Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (2015). Nursing Informatics Entry-to-Practice Competencies for Registered Nurses. Retrieved from https://www.casn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Nursing-Informatics-Entry-to-Practice-Competencies-for-RNs_updated-June-4-2015.pdf

Canadian Nurses Association (2006). E-Nursing Strategy for Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/e-nursing-strategy-for-canada.pdf?la=en

Canadian Nurses Association (2015). Position Statement: Nursing Information and Knowledge Management. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/nursing-information-and-knowledge-management_position-statement-2006.pdf?la=en

Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association (2017). Joint Position Statement: Nursing Informatics. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/-/media/cna/page-content/pdf-fr/nursing-informatics-joint-position-statement.pdf

Collins, S., Yen, P. Y., Phillips, A., Kennedy, M. (2017). Nursing informatics competency assessment for the nurse leader: The Delphi study. Journal of Nursing Administration, 47(4), 212-218.

Dyess, S., Sherman, R., Pratt, B., Chiang-Hanisko, L., (2016) Growing Nurse Leaders: Their Perspectives on Nursing Leadership and Today’s Practice Environment. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing,21(1)

Green, B.N., Johnson, C.D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101-117.

Hartley, L. A. (2014). Implementing shared governance in a patient care support industry: Information technology leading the way. Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(6), 315-317.

Honey, M., & Westbrooke, L. (2016). Evolving national strategy driving nursing informatics in New Zealand. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 225, 183-187. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-658-3-183

Hussey, P., Adams, E., & Shaffer, F. A. (2015). Nursing informatics and leadership, an essential competency for a global priority: Health. Nurse Leader, 13(5), 52-57.

Hussey, P., & Kennedy, M. A. (2015). Instantiating informatics in nursing practice for integrated patient centered holistic models of care: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(5), 1030-1041.

Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice (2017). Appendix F: Non-Research Evidence Appraisal Tool in Buccheri, R., Sharifi, C. (2017). Critical Appraisal Tools and Reporting Guidelines for Evidence-Based Practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(6), 463-472

Kerfoot, K. M. (2015). On leadership. intelligently managed data: Achieving excellence in nursing care. Nursing Economic$, 33(6), 342-343.

Leach, L., & McFarland, P. (2014). Assessing the Professional Development Needs of Experienced Nurse Executive Leaders. Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(1), 51-62.

Lloyd, J. & Ferguson S. (2017). Innovative information technology solutions: Addressing current and emerging nurse shortages and staffing challenges worldwide.Nursing Economic$, 35(4), 211-212.

Mays, N., Pope, C., & Popay, J. (2005). Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10 (Suppl 1), 6–20.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Nagle, L. M., Crosby, K., Frisch, N., Borycki, E., Donelle, L., Hannah, K., . . . Shaben, T. (2014). Developing entry-to-practice nursing informatics competencies for registered nurses. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 201, 356-363.

Okoli, C., & Pawlowski, S. D. (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management, 42(1), 15-29

Phillips, A., Yen, P., Kennedy, M., & Collins, S. (2017). Opportunity and approach for implementation of a self-assessment tool: Nursing informatics competencies for nurse leaders (NICA-NL)…NI 2016, Switzerland. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 232, 207-211. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-738-2-207

Remus, S. (2016). Advancing the digital health discourse for nurse leaders. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 225, 412-416. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-658-3-412

Ritchie, L., & Blair, W. (2017). The challenges of nursing leadership. Kai Tiaki: Nursing New Zealand, 23(7), 24.

Saul, J. E., Best, A., Noel, K. (2014). Implementing Leadership in Healthcare: Guiding Principles and a New Mindset. Healthcare Solutions.

Simpson, R. L. (2010). Challenging Leadership Status Quo. In: Ball M. et al. (eds) Nursing Informatics. Health Informatics. Springer, London.

Simpson, R. L. (2013). Chief nurse executives need contemporary informatics competencies.

Nursing Economics, 31(6), 277.

Solman, A. (2017). Nursingleadershipchallengesand opportunities. Journal of Nursing

Management, 25(6).

Staggers, N., Elias, B. L., Makar, E., & Alexander, G. L. (2018). The imperative of solving nurses’ usability problems with health information technology.Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(4), 191-196.

Strudwick, G. (2016). An international perspective on nursing informatics: In conversation with Nick Hardiker.Nursing Leadership (1910-622X), 28(4), 36-37.

Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (2014). The Leadership Imperative: TIGER’s Recommendations for Integrating Technology to Transform Practice and Education. Retrieved from https://www.himss.org/tiger-s-recommendations-integrating-technology-transform-practice-and-education

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research

(COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6). Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/19/6/349/1791966

Troseth, M. R. (2014). TIGER in action: The leadership imperative report & international engagement.Nursing Informatics Today, 29(3), 10-11.

Weaver, C., & O’Brien, A. (2016). Transforming clinical documentation in EHRs for 2020: Recommendations from University of Minnesota’s big data conference working group.Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 225, 18-22. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-658-3-18

Westra, B. L., Clancy, T. R., Sensmeier, J., Warren, J. J., Weaver, C., & Delaney, C. W. (2015). Nursing knowledge: Big data science-implications for nurse leaders.Nursing Administration Quarterly, 39(4), 304-310.

Based Practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(6), 463-472.

Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (2015). Nursing Informatics Entry-to-Practice Competencies for Registered Nurses. Retrieved from https://www.casn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Nursing-Informatics-Entry-to-Practice-Competencies-for-RNs_updated-June-4-2015.pdf

Canadian Nurses Association (2006). E-Nursing Strategy for Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/e-nursing-strategy-for-canada.pdf?la=en

Canadian Nurses Association (2015). Position Statement: Nursing Information and Knowledge Management. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/nursing-information-and-knowledge-management_position-statement-2006.pdf?la=en

Canadian Nursing Informatics Association-Canadian Nurses Association (2017). Joint Position Statement: Nursing Informatics. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/-/media/cna/page-content/pdf-fr/nursing-informatics-joint-position-statement.pdf

Collins, S., Yen, P. Y., Phillips, A., Kennedy, M. (2017). Nursing informatics competency assessment for the nurse leader: The Delphi study.Journal of Nursing Administration, 47(4), 212-218.

Dyess, S., Sherman, R., Pratt, B., Chiang-Hanisko, L., (2016) Growing Nurse Leaders: Their Perspectives on Nursing Leadership and Today’s Practice Environment. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing,21(1)

Green, B.N., Johnson, C.D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101-117.

Hartley, L. A. (2014). Implementing shared governance in a patient care support industry: Information technology leading the way.Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(6), 315-317.

Honey, M., & Westbrooke, L. (2016). Evolving national strategy driving nursing informatics in new zealand.Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 225, 183-187. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-658-3-183

Hussey, P., Adams, E., & Shaffer, F. A. (2015). Nursing informatics and leadership, an essential competency for a global priority: EHealth

Hussey, P., & Kennedy, M. A. (2015). Instantiating informatics in nursing practice for integrated patient centered holistic models of care: A discussion paper.Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(5), 1030-1041.

Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice (2017). Appendix F: Non-Research Evidence

Appraisal Tool in Buccheri, R., Sharifi, C. (2017). Critical Appraisal Tools and Reporting Guidelines for Evidence-Based Practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(6), 463-472

Kerfoot, K. M. (2015). On leadership. intelligently managed data: Achieving excellence in nursing care.Nursing Economic$, 33(6), 342-343.

Leach, L., & McFarland, P. (2014). Assessing the Professional Development Needs of

Experienced Nurse Executive Leaders. Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(1), 51-62.

Lloyd, J., Ferguson S. (2017). Innovative information technology solutions: Addressing current and emerging nurse shortages and staffing challenges worldwide.Nursing Economic$, 35(4), 211-212.

Mays, N., Pope, C., & Popay, J. (2005). Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10 (Suppl 1), 6–20.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Nagle, L. M., Crosby, K., Frisch, N., Borycki, E., Donelle, L., Hannah, K., . . . Shaben, T. (2014). Developing entry-to-practice nursing informatics competencies for registered nurses.Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 201, 356-363.

Okoli, C., & Pawlowski, S. D. (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management, 42(1), 15-29

Phillips, A., Yen, P., Kennedy, M., & Collins, S. (2017). Opportunity and approach for implementation of a self-assessment tool: Nursing informatics competencies for nurse leaders (NICA-NL)…NI 2016, Switzerland.Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 232, 207-211. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-738-2-207

Remus, S. (2016). Advancing the digital health discourse for nurse leaders.Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 225, 412-416. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-658-3-412

Ritchie, L., & Blair, W. (2017). The challenges of nursing leadership. Kai Tiaki: Nursing New Zealand,23(7), 24.

Saul, J.E., Best, A., Noel, K. (2014). Implementing Leadership in Healthcare: Guiding Principles and a New Mindset. Healthcare Solutions.

Simpson, R. L. (2010). Challenging Leadership Status Quo. In: Ball M. et al. (eds) Nursing Informatics. Health Informatics. Springer, London.

Simpson, R. L. (2013). Chief nurse executives need contemporary informatics competencies. Nursing Economics, 31(6), 277.

Solman, A. (2017). Nursingleadershipchallengesand opportunities. Journal of Nursing Management, 25(6).

Staggers, N., Elias, B. L., Makar, E., & Alexander, G. L. (2018). The imperative of solving nurses’ usability problems with health information technology.Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(4), 191-196.

Strudwick, G. (2016). An international perspective on nursing informatics: In conversation with Nick Hardiker.Nursing Leadership (1910-622X), 28(4), 36-37.

Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (2014). The Leadership Imperative: TIGER’s Recommendations for Integrating Technology to Transform Practice and Education. Retrieved from https://www.himss.org/tiger-s-recommendations-integrating-technology-transform-practice-and-education

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research

(COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6). Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/19/6/349/1791966

Troseth, M. R. (2014). TIGER in action: The leadership imperative report & international engagement.Nursing Informatics Today, 29(3), 10-11.

Weaver, C., & O’Brien, A. (2016). Transforming clinical documentation in EHRs for 2020: Recommendations from University of Minnesota’s big data conference working group.Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 225, 18-22. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-658-3-18

Westra, B. L., Clancy, T. R., Sensmeier, J., Warren, J. J., Weaver, C., & Delaney, C. W. (2015).

Nursing knowledge: Big data science-implications for nurse leaders.Nursing Administration Quarterly, 39(4), 304-310.

Biography

Andrea Knox, RN, BSN, CON(c)

Andrea is a nationally certified oncology nurse and currently holds the position of Senior Practice Leader for Nursing at BC Cancer – Kelowna. Andrea has a strong interest in the field of nursing informatics and is passionate about supporting the professional practice of oncology nurses across BC.