From Data to Knowledge and Practice: A Framework for Nurses’ Use of Electronic Health Records

by Shuhong Luo, EdD, MSN, RN & Virginia Young, MLS

SUNY Upstate Medical University

Background

A low quality of care is the most important challenge in acute care settings. Electronic health records (EHRs) were implemented with the goal of improving quality of care and patient safety (The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), 2017). Nurses are one of the main stakeholders and frontline users of EHRs. Failing to use evidence in nursing practice contributes to low quality of care (Correa-de-Araujo, 2016). A gap usually exists between the data that nurses enter into EHRs and how those data are used as evidence for practice, especially in acute settings. This gap could lead not only to the underuse of EHR data, but also to the incorrect use of patient-centered evidence or the overuse of unhelpful guidance for nursing practice. All of these consequences will jeopardize the safety of patients. A number of studies in the literature have highlighted the importance of evidence that guides practice, particularly research evidence (Boswell & Cannon, 2018; Correa-de-Araujo, 2016). However, the use of EHRs as a knowledge base for nurses and the systematic use and evaluation of data stored in EHRs (e.g., a pattern of caring for a type of patient in local hospitals) are rarely reported in the literature. Therefore, the process of nurses’ use of EHRs is largely about their data entry rather than data retrieval from EHRs as evidence to guide nursing practice.

Instead of focusing on nurses as one of the stakeholders in using EHRs, the literature to date has tended to focus on physicians’ use of EHRs for decision-making and diagnosis ( The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), 2017). The literature on nurses’ use of EHRs is mainly focused on data entry and data quality ( American Nurses Association (ANA), 2012). However, little is known about how nurses use EHRs as a knowledge management system (KMS), especially in the direct care of patients in an acute setting.

Additionally, there are no clearly articulated models or frameworks that describe the entire process of nurses’ use of EHRs in more detail and evaluate interventions more robustly. The models related to the use of EHRs in the literature are not nurse focused (EHR Impact, 2008; Karim, Ahmad, & Mohamed, 2011). The model of ‘knowledge to action’ framework (Graham et al., 2006) explained how knowledge, including nursing knowledge, can be transferred to practice and vice versa; however, it does not specify how nurses query and synthesize the data from EHRs to obtain knowledge and thus guide their practice. The adequacy of this model in explaining how knowledge is transferred to practice remains unknown (Ward, House, & Hamer, 2009).

Studies in other related areas such as machine learning and deep learning have also failed to adequately explain the process of nurses’ use of EHRs as a knowledge base to guide their practice. Instead of focusing on the broad picture of the journey from data entry to data retrieval, research has tended to assume that those who enter and use data may be from different populations. For example, the nurses who enter the data may work in the frontline at the bedside, whereas those who use the data may work at patient registration, the billing office, etc. (Karim et al., 2011). However, studies have shown that no single sector of the entire process is effective in all circumstances, suggesting that the process of nurses’ use of EHRs needs to be considered as a whole.

One of the major difficulties with studying nurses’ use of EHRs is that researchers presume that when nurses enter data into EHRs, they may not expect to become consumers of the data they have entered. Both nurses and the data they have entered tend not to acknowledge the potential complexity of using the data later. Researchers may seek evidence that will guide nursing practice in the literature, textbooks, clinical guidelines, or various resources that are separate from the data that nurses have entered.

To advance the theory and practice of nurses’ use of EHRs to improve the quality of patient care, future research will need to address the issues outlined above. This includes moving away from isolated perceptions of either data entry or data usage and descriptions of nurses’ use of EHRs towards a broader explanation of the process cycle, consideration of data in EHRs as a part of knowledge in addition to research, and refining and testing of factors for designing and evaluating interventions.

This study articulates the key components that are presumed to be involved in the process of nurses’ use of EHRs and produces a framework that can be used to plan and evaluate interventions to improve nurses’ use of EHRs. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development of a conceptual framework that articulates the key components of the process of nurses’ use of EHRs and to present it as a resource for future empirical research on this process.

Methods

Design

Based on the suggestions of Hymovich (1993) regarding the steps for developing a conceptual framework, we conducted an extensive review of the literature on the relevant topic of nurses’ use of EHRs. Then, we summarized, thematically analyzed, and synthesized evidence from the literature. Third, we isolated and described the important variables and phenomena of concerns that have not been previously named in terms of the concerns of this study. Last, we aggregated themes to generate a conceptual framework of nurses’ use of EHRs.

Search Strategy

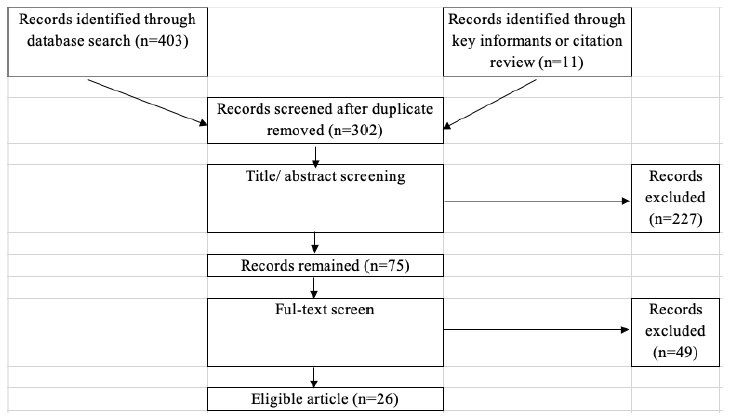

A medical librarian conducted searches in PubMed and the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Subject headings and related search terms included “electronic health records,” “EHR or EMR,” “nurses,” “data” “decisionmaking,” “decision making, clinical,” “knowledge,” “knowledge management system,” and “challenge.” The date limits were set until December 2013. The initial database searches retrieved 403 records. We also identified 11 records through key informants or citation reviews, obtaining 302 articles after the duplicates of initial records were removed.

Selection of Articles

After the duplicates were removed, two reviewers independently screened all abstracts of the studies based on the inclusion criteria, which were studies about nurses’ use of EHRs. Abstracts selected from this narrative review for full text analysis focused on the comfort level of nurses using concepts associated with research conducted with EHR data and the value of EHR data to inform clinical practice. Seventy-five articles remained after the abstract review. Next, two reviewers read and screened the full texts of the included articles independently. If there were discrepancies concerning eligibility, the two reviewers discussed them until they achieved a consensus or discussed them with the third reviewer when necessary. Twenty-six studies were included in the final review. The literature selection process is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Literature Selection Process

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is a qualitative data analysis method. Researchers use it to identify, analyze, and interpret the theme or patterned meaning of qualitative data (Rohleder & Lyons, 2015). A total of 26 papers and reports were read in detail. We identified nine different themes that explained all or part of the process of nurses’ use of EHRs and the type of process. We then used the results of this thematic analysis to build a conceptual framework of the process of nurses’ use of EHRs.

Results and Discussion

Components of Nurses’ Use of EHRs

Environment

Environment means the particular practice setting in which nurses work. We used an acute setting as an example in this paper. Health care in an acute setting is transactional, and patient safety is more likely to be threatened by a patient’s status changing more frequently, a medication needing to be administered urgently, or a patient’s admittance to the hospital in critical condition (Sockolow, Rogers, Bowles, Hand, & George, 2014).

Nurses

Nurses are among the main stakeholders of EHRs. To provide the best quality of care, especially in an acute care setting that requires a prompt, correct, and evidence-based nursing practice along with the best clinical judgment, nurses must have an overall understanding of the patient and a set of goals and plans for that patient. Before seeing patients to conduct any nursing practice, nurses need to not only understand them but also make decisions regarding patient care using evidence from the research, past experiences, and other knowledgeable health care team members (Camicia et al., 2013). However, nurses usually work shifts. They usually have to make the time to read the notes in EHRs to understand patients and use this knowledge to manage patient care before they visit the patients. However, the nursing profession is not included in several models that are related to the use of EHRs (EHR Impact, 2008; Karim et al., 2011).

Knowledge

From the perspective that knowledge can be transferred to nursing practice, knowledge in this study is defined as individual tacit knowledge, new ideas or innovations, clinical expertise, patient values, research results, skills, and other evidence (Boswell & Cannon, 2018; Graham et al., 2006; Ward et al., 2009). Tacit knowledge is a type of knowledge that works together with explicit knowledge (Wiig, 1993). According to Nazim and Mukherjee (2016), explicit knowledge tends to represent the final outcome of a performance, whereas tacit knowledge is the know-how or the process required to produce the final outcome. Tacit knowledge is the “know-how” knowledge attained from practical experience and evidence from research over time (Benner, 2001), whereas explicit knowledge is formal knowledge that can be written and codified (Anderson & Willson, 2009). Nurses may obtain explicit knowledge from resources such as textbooks, classrooms, clinical guidelines, and EHR knowledge bases. However, explicit knowledge may be difficult for nurses to apply flexibly to their daily practice in various settings and in complicated clinical encounters. Nurses, especially novices, need tacit knowledge to guide their daily practice. Tacit knowledge is usually hard to articulate because it is not a manual or how-to process. Nurses who possess tacit knowledge are usually highly skilled, experienced, and expert nurses (Stead, Lin, & National Research Council [U.S.], 2009). Tacit knowledge usually needs to be captured, collected, and shared to become explicit knowledge (Graham et al., 2006). Tacit knowledge about a typical patient taken care of by nurses is stored within the EHR data. When other nurses retrieve those data, tacit knowledge helps them construct a mental model of how to treat the patient before taking care of him or her (Stead et al., 2009).

Practice

The concept of nursing practice encompasses the use of knowledge by nurses. To optimize clinical outcomes and quality of life, nurses’ practice needs to be evidence based (Boswell & Cannon, 2018). Before nurses take any action to care for patients, they should use at least two mental processes: (1) collect the best available evidence, their clinical expertise, and patient values and preferences; and (2) integrate the collected information to make decisions about patient care. In other words, nurses need to have a mental model based on what they already know before seeing their patients. A mental model is what people know (or think they know) about a condition (Johnsonlaird, 1981). Craik (1967) stated that humans approach tasks with mental models created out of their prior experience and understanding. Additionally, mental models help knowledge and information processing become more efficient by making it unnecessary to construct understanding from scratch each time similar stimuli are encountered. The mental model will guide nurses to make decisions on how to provide patient care. With a mental model prepared before seeing the patient, nurses are able to conduct practice based on evidence and are able to allow the knowledge to be transferred to practice, as illustrated in the knowledge-to-action framework (Graham et al., 2006). This framework describes the process of how knowledge is translated to evidence-based practice.

Data

The components of EHRs include patient management (e.g., patient demographics, insurance information, contact information, registration, admission, transfer and discharge, medical history, vital signs, diagnoses, medications, immunization dates, allergies), clinical data (e.g., computerized provider order entries, progress notes), laboratory data (e.g., lab and test results, orders, billing), radiology information, and the billing system ( The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), 2013). In this paper, we consider EHR data to be the information transferred between nurses and EHRs and between EHRs and KMS. Nurses not only input data (e.g., patients’ vital signs and progress notes) into the EHR system but also use the EHR data as a knowledge base to help them make decisions in regard to their actions before interacting with patients. The data are the reflection of the knowledge possessed by nurses who enter them into EHRs. The data in EHRs also help to construct a mental model for those who retrieve and read the EHR data.

EHRs

EHRs have significantly improved the quality of care ( The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), 2017). EHRs are more than just a static repository for patient data. They are a system that combines data, knowledge, and software tools to help nurses’ evidence-based practice. However, most researchers have investigated the use of EHRs as a clinical decision-making tool, an information management system, or an alert system to support providers’ processes of diagnosis, prescriptions, administration systems (van der Veen et al., 2018), referral decisions (Bowles, Hanlon, Holland, Potashnik, & Topaz, 2014), clinical criteria establishment (Apsey et al., 2014; Dixon, Thanavaro, Thais, & Lavin, 2013; Mackey et al., 2014), and symptom management (Beckerle & Lavin, 2013). The functions of EHRs for nurses are usually patient registration and billing (EHR Impact, 2008; Karim et al., 2011). We found few literature sources that discussed the use of EHRs as an electronic nursing KMS in a nursing practice acute setting.

KMS

EHRs have massive potential to serve as a KMS. The data in EHRs can be used to conduct retrospective reviews of patient records to support nurses in their work by, for example, helping nurses critically interpret the data stored in EHRs to gain insight into patients and using nursing knowledge for symptom and function management. The use of EHRs as a KMS in nursing practice has been recognized since 2009, when Anderson and Willson (2009) examined the concept of knowledge management as a framework for identifying, organizing, analyzing, and translating nursing knowledge into daily practice. In Poland, Bartnicka (2017) proposed three stages for developing an electronic knowledge management model in nursing work. In Iran, Namnabati et al. (2017) designed and implemented an electronic nursing management system so that nurses could carry out standard care and documentation for a neonatal intensive care unit with a high level of nursing satisfaction. However, the workflow integration process was unclear. Furthermore, the system did not use existing EHR data.

Process of Nurses’ Use of EHRs

Data entry

After nurses complete a task, they translate their action into documents in EHRs (e.g., texts, checkbox, images, etc.) during data entry. This process involves nurses capturing, collecting, and synthesizing essential information that they previously knew intrinsically and sharing that information through EHRs. Therefore, the process of data entry is when the nurses’ tacit knowledge becomes explicit knowledge that others can understand.

There are some shortcomings to data entry. For example, nurses may spend more time entering data than using data (Stead et al., 2009), and they can be frustrated with their inability to access the information they need to communicate about patients, particularly when a patient’s status changes, information availability slows, and information is not available in real time to guide decision-making (Gephart, Bristol, Dye, Finley, & Carrington, 2016).

Data retrieval

To use EHR data as tacit knowledge, nurses who are learning need to leverage the documentation and data retrieval, analysis, prediction, and interpretation to yield the best individualized, evidenced-based plan of patient care. In a work environment overloaded with information, nurses experience an increased pace and workload. They must do more faster and work smarter. However, the amount of EHR information is huge. There are several barriers that leave nurses unable to use this data to direct nursing care. The following sections describe and discuss the barriers in acute settings.

Nonmeaningful information

Sometimes, the data are not meaningful to nurses and do not serve the nursing practice directly. These data may include some uncertain and potentially conflicting information from various sources such as clinical assessment data, data from tests and monitoring equipment, clinical guidelines, journal articles, memories from personal clinical experience, medical records from other health care organizations, informal observations and thoughts from colleagues, and patient commentary and insights (Stead et al., 2009). The overload of raw data may make it more likely that nurses will overlook some important higher-order considerations and get lost amid the big data.

Data that are not organized and synchronized

The data nurses need are usually scattered throughout medical records. Some EHR systems are not user-friendly. The data are not organized and synchronized in a systematic way and cannot provide an overall picture of a patient’s status and care needs (DeZarn, 2006). In some health care settings, nurses do not have full access to the appropriate functionality of an EHR data report. It is challenging for nurses to manually locate significant information about the patient’s clinical status or changing condition within the EHR system. They have to search and sift through raw data about patients, integrate the data with their nursing knowledge, and synthesize and deliberate over comprehensive, relevant information to understand their patients.

Data that does not reflect standard nursing performance

The current data may not reflect standard nursing performance (Camicia et al., 2013), which requires nurses to think (assess); make clinical judgments (diagnose); identify outcomes; and plan, intervene, and evaluate care. However, nurses may perceive their roles to mostly involve data documentation in the assessment stage. There might be few documented professional analyses of the data, a nursing diagnosis, or a plan of nursing care that is appropriate to the patient’s needs documented in the EHR system (Keenan, Yakel, Dunn Lopez, Tschannen, & Ford, 2013).

Not real-time data

If any performance is not documented, it is considered not done (Lavin, Harper, & Barr, 2015). Nurses enter data synchronously and asynchronously to record the nursing care provided and patients’ responses. The disruptive nature of interruptions in an acute setting may cause nurses to work around the EHRs (Sockolow et al., 2014). When nurses document a fact after they have completed a task or forget to document it, the data in EHRs cannot reflect what is happening in real time and might not support the clinical judgment of the nurses at the time of patient care. This undocumented performance may lead to redundant work (Stead et al., 2009).

Ill-structured data

The data might be ill-structured and may not follow any standard format or terminology, such as free text. The reason for this might be that nurses want to use free text to save time (Bowles, 2014), especially in acute health care settings, where frequent interruptions, high workload, and new work are usually involved. Additionally, the reason might be that the nursing professional does not know a language supported by nationally (or internationally) agreed codes (Alderden & Cummins, 2016).

Ill-structured data may make it difficult for nurses to understand some statements and phrases, thus limiting data and knowledge reuse. Semantic interoperability is almost nonexistent in ill-structured texts, making it difficult to retrieve information. Labour using natural language processing and data mining is needed to clean and categorize responses to make the data useful (Stead, Lin, & National Research Council [U.S.], 2009). Nurses have to devote precious cognitive resources and a great deal of time and energy to find, analyze, and transform data into useful information. Thus, they have less time to spend with patients, and time spent with patients is precious. Workarounds are common because of missing or mismatched information (Stead et al., 2009). Nurses might not use any data as evidence to support their decisions or workflow; therefore, their practice might not be evidence based. However, tools to support nurses’ clinical decision-making are limited in EHRs, especially tools that fit nurses’ workflow (O?Brien, Weaver, Settergren, Hook, & Ivory, 2015).

Developing a Framework for Nurses’ Use of EHRs

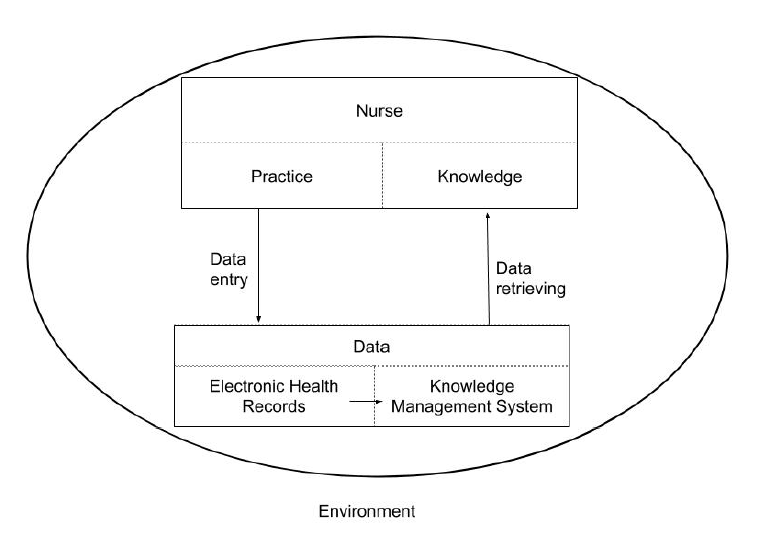

Having identified seven common components and two types of related processes of the nurses’ use of EHRs, we built these into one conceptual framework, shown in Figure 2. Different from other frameworks related to EHRs, nurses are the main stakeholders of EHRs and KMS. In this framework, nurses interact with EHRs in two ways: data entry and data retrieval. Nurses are not only the creators of data, which used to be perceived as the major role of nurses in EHRs, but also the consumers of the same data. We do not believe that nurses’ use of EHRs is a linear process; rather, it is an interactive, multidirectional process. The framework illustrates that nurses’ practice is documented as data in EHRs. The data will be retrieved and used as knowledge, which will serve as evidence to guide nursing practice. This process is consistent with the literature on knowledge transfer that includes knowledge inquiry and synthesis (Graham et al., 2006).

Figure 2: Process of nurses’ use of EHR

This framework highlights KMS as a way for nurses to use EHRs. It specifically provides tacit knowledge that is directly interpreted from patients’ cases recorded in EHRs. This type of knowledge is unique and cannot be found in a textbook, a manual with standard procedures, or in the literature because it may not address or include the local patient population. The data retrieved from EHRs as knowledge will prepare nurses to have a mental model about the patients they see before they visit them (Stead et al., 2009). The concept of a mental model is consistent with the planned-action theories or models that focus on the meta-cognition of knowledge use (Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2013).

This framework helps to evaluate the process of nurses’ use of EHRs and to identify any problems. For instance, the unsuccessful utilization of EHR data might lead to a new consideration of the underlying issue or problem related to other components of the framework (i.e., nurses’ workflow, environment, or the EHR system’s semantic interpretation of raw data about patients). The framework also provides a foundation for future interventions that will help to improve the interactive process of nurses’ use of EHRs for better patient outcomes. For example, the gap between EHRs being transferred to KMS allows researchers to develop interventions for improvement (e.g., semantic interpretation, machine learning, deep learning).

Conclusion

EHRs have been implemented in health care settings for decades in the United States and Canada. Nurses need to effectively use the data stored in EHRs in fast-paced environments to support their evidence-based practice and provide the best quality of care and patient safety. We developed a conceptualframework based on published articles on the use of EHRs in nursing. The proposed framework could be used as a basis for gatheringevidence for planning or evaluating interventions to raise awareness of the importance of documentation as a data source and to seek ways to use data in EHRs for research and quality measurement.

References

Alderden, J., & Cummins, M. (2016). Standardized nursing data and the oncology nurse. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20(3), 336–338. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.CJON.336-338

American Nurses Association (ANA). (2012). Care coordination and registered nurses’ essential role: ANA Position Statement. Retrieved from http://nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/Policy-Advocacy/Positions-and-Resolutions/ANAPositionStatements/Position-Statements-Alphabetically/Care-Coordination-and-Registered-Nurses-Essential-Role.html

Anderson, J. A., & Willson, P. (2009). Knowledge management: organizing nursing care knowledge. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 32(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CNQ.0000343127.04448.13

Apsey, H. A., Coan, K. E., Castro, J. C., Jameson, K. A., Schlinkert, R. T., & Cook, C. B. (2014). Overcoming clinical inertia in the management of postoperative patients with diabetes. Endocrine Practice: Official Journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, 20(4), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP13366.OR

Bartnicka, J. (2017). Knowledge management process in nursing practice. Innovation in Management and Production Engineering, 121–134.

Beckerle, C. M., & Lavin, M. A. (2013). Association of self-efficacy and self-care with glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum, 26(3), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.26.3.172

Benner, P. E. (2001). From novice to expert: excellence and power in clinical nursing practice(Commemorative ed). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall.

Boswell, C., & Cannon, S. (Eds.). (2018). Introduction to nursing research: incorporating evidence-based practice(Fifth edition). Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Bowles, K. H. (2014). Developing evidence-based tools from EHR data. Nursing Management (Springhouse), 45(4), 18–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000444881.93063.7c

Bowles, K. H., Hanlon, A., Holland, D., Potashnik, S. L., & Topaz, M. (2014). Impact of discharge planning decision support on time to readmission among older adult medical patients. Professional Case Management, 19(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PCAMA.0000438971.79801.7a

Camicia, M., Chamberlain, B., Finnie, R. R., Nalle, M., Lindeke, L. L., Lorenz, L., … McMenamin, P. (2013). The value of nursing care coordination: A white paper of the American Nurses Association. Nursing Outlook, 61(6), 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2013.10.006

Correa-de-Araujo, R. (2016). Evidence-based practice in the United States: Challenges, progress, and future directions. Health Care for Women International, 37(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2015.1102269

Craik, K. J. W. (1967). The nature of explanation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rwhi20/

DeZarn, T. L. (2006). Darbyshire P (2004) ‘Rage against the machine?’: nurses’ and midwives’ experiences of using computerized patient information systems for clinical information. Journal of Clinical Nursing13, 17-25. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(2), 237–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01180.x

Dixon, K., Thanavaro, J., Thais, A., & Lavin, M. A. (2013). Amiodarone Surveillance in Primary Care. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 9(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2012.09.019

EHR Impact. (2008). The conceptual framework of interoperable electronic health record and ePrescribing systems. European Commission. Retrieved from http://www.ehr-impact.eu/downloads/documents/EHRI_D1_2_Conceptual_framework_v1_0.pdf

Gephart, S. M., Bristol, A. A., Dye, J. L., Finley, B. A., & Carrington, J. M. (2016). Validity and reliability of a new measure of nursing experience with unintended consequences of electronic health records. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 34(10), 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000285

Graham, I. D., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

Hymovich, D. P. (1993). Designing a conceptual or theoretical framework for research. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 10(2), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/104345429301000237

Johnsonlaird, P. (1981). Mental models in cognitive science. Cognitive Science, 4(1), 71–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(81)80005-5

Karim, N., Ahmad, M., & Mohamed, N. (Eds.). (2011). A framework for electronic health record (EHR) implementation impact on system service quality and individual performance among healthcare practitioners. In 10th WSEAS International Conference on E-Activities (E-ACTIVITIES’11)(pp. 197–201). Greece: WSEAS Press.

Keenan, G., Yakel, E., Dunn Lopez, K., Tschannen, D., & Ford, Y. B. (2013). Challenges to nurses’ efforts of retrieving, documenting, and communicating patient care information. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 20(2), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000894

Lavin, M. A., Harper, E., & Barr, N. (2015). Health information technology, patient safety, and professional nursing care documentation in acute care settings. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 20(2), 6.

Mackey, P. A., Boyle, M. E., Walo, P. M., Castro, J. C., Cheng, M.-R., & Cook, C. B. (2014). Care directed by a specialty-trained nurse practioner or physician assistant can overcome clinical inertia in management of inpatient diabetes. Endocrine Practice: Official Journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, 20(2), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP13201.OR

Namnabati, M., Taleghani, F., Varzeshnejad, M., Yousefi, A., Karjoo, Z., & Safiri, S. (2017). Nursing care and documentation assistant with an electronic nursing management system in neonatal intensive care unit. Iranian Journal of Neonatology IJN, (2). https://doi.org/10.22038/ijn.2017.8916

Nazim, M., & Mukherjee, B. (2016). An Introduction to Knowledge Management. In Knowledge Management in Libraries(pp. 1–26). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100564-4.00001-6

O?Brien, A., Weaver, C., Settergren, T. (Tess), Hook, M. L., & Ivory, C. H. (2015). EHR documentation: The hype and the hope for improving nursing satisfaction and quality outcomes. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 39(4), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000132

Rohleder, P., & Lyons, A. C. (Eds.). (2015). Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sockolow, P. S., Rogers, M., Bowles, K. H., Hand, K. E., & George, J. (2014). Challenges and facilitators to nurse use of a guideline-based nursing information system: recommendations for nurse executives. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 27(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.10.005

Stead, W. W., Lin, H., & National Research Council (U.S.) (Eds.). (2009). Computational technology for effective health care: immediate steps and strategic directions. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12572

Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., & Graham, I. D. (Eds.). (2013). Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice(2nd ed). Chichester, West Sussex, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley/BMJ Books.

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). (2013). What information does an electronic health record (EHR) contain? HealthIT.gov. Retrieved from https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-information-does-electronic-health-record-ehr-contain

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). (2017). Improved diagnostics & patient outcomes. HealthIT.gov. Retrieved from https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-basics/improved-diagnostics-patient-outcomes

van der Veen, W., van den Bemt, P. M., Wouters, H., Bates, D. W., Twisk, J. W., de Gier, J. J., … Mangelaars, I. (2018). Association between workarounds and medication administration errors in bar-code-assisted medication administration in hospitals. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(4), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocx077

Ward, V., House, A., & Hamer, S. (2009). Developing a framework for transferring knowledge Into action: A thematic analysis of the literature. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 14(3), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2009.008120

Wiig, K. M. (1993). Knowledge management foundations: thinking about thinking: how people and organizations create, represent, and use knowledge. Arlington, Tex: Schema Press.

Author Bios:

Shuhong Luo (Corresponding author):

Shuhong Luo, EdD, MSN, RN is an Assistant Professor in SUNY Upstate Medical University. Luo received her bachelor’s degree in nursing from Peking University Health Science Center, master’s degree in nursing informatics from University of Nebraska Medical Center, and doctoral degree in educational technologies from University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Dr. Luo’s research interests include implementing technologies (e.g. mobile apps) in healthcare and mixed methods research approach in nursing.

Virginia Young:

Virginia Young, MLS, is an Associate Librarian in SUNY Upstate Medical University. She holds a master’s degree in library science.