An Exploration of a Nursing Cohort’s Online Learning Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Communication, Comradery, and Comprehension

Donna Abraham, BSc., Andrea Bissonnette, BA., Jessica Cheung, BSc., Lindsay Corbould, BSc., Pawan Dhaliwal, BSc., Annu Kumari, MSc., Nathalie Nguyen, BSc., Tiffany Shahrokhi, BSc., and Camille de Vera, BSc.

Faculty of Health, Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Citation: Abraham, D., Bissonnette, A., Cheung, J., Corbould, L., Dhaliwal, P., Kumari, A., Nguyen, N., Shahrokhi, T. & de Vera, C. (2021). An Exploration of a Nursing Cohort’s Online Learning Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Communication, Comradery, and Comprehension. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 16(2). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=9070

Abstract

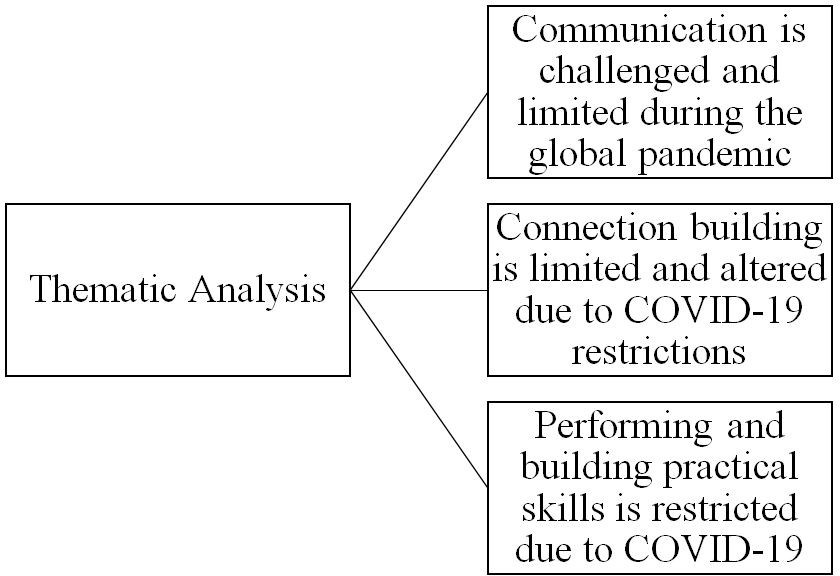

The aim of this case study was to examine the experiences of nursing students from a fall 2020 cohort in regard to three aspects of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: communication, comradery, and comprehension. This was a descriptive qualitative study. A convenience sample of eight students enrolled in together in a research course was selected. Thematic analysis revealed three themes: (1) communication is challenged and limited during the global pandemic, (2) connection building is limited and altered due to COVID-19 restrictions and (3) performing and building practical skills is restricted due to COVID-19. Almost all the participants reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has limited their ability to communicate and connect with one another as a cohort and has restricted their opportunity to practice and build the clinical skills necessary for the successful completion of the program. While the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the students to be disconnected physically, they remain connected in these shared concerns.

Introduction

The recent rapid advancement in technology has provided the world with new ways of accomplishing daily tasks. These technological advancements have affected everyone’s life in various aspects such as business, economy and education. In education, these innovations have enabled online learning to emerge. Online learning was previously a novel trend that recently became mainstream (Kentnor, 2015).

Online learning or eLearning is essentially a modern form of distance education which has been around since the 1800s through various mediums. Online learning utilizes computers and the Internet to deliver course content online (Kentnor, 2015). This form of schooling was based on the premise of education being delivered without face-to-face interaction between the student and the teacher. According to Sener (2012), the initial focus of online learning was to provide access to education; however, the focus on online learning now, is the quality of education provided. For the purpose of this research paper, hybrid learning (a blend of online and in class learning), and purely online learning are both considered to be online learning.

There have been various explorations on the benefits and challenges students face with online learning (Gerkin, 2009; Guri-Rosenblit & et al., 2011; Kemp & Grieve, 2014; Kim, 2006; Pei & Wu, 2019). Specifically, various studies have also been done in the field of online learning delivered to health care workers and licensed health professionals (Masic, 2008; George & et al., 2014; Vaona & et al., 2018). When used in nursing, online learning was found to be effective due to “increased flexibility, access, and cost-effectiveness in nursing education” (Holly, 2009). However, there are also some barriers identified with this form of learning in nursing, such as lack of computer skills and insufficient time (Atack & Renkin, 2002).

Furthermore, several studies have explored the experiences and perceptions of nursing students with online learning (Ali & et al., 2004; Atack, 2003; Atack & Rankin, 2002). However, there has not been any studies undertaken that focus on the experiences, perceptions, and attitudes of nursing students with online learning in the midst of a global pandemic – in this instance, COVID-19. This case study explores the experiences of a nursing cohort with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic – and how some changes brought by the pandemic have affected their learning. This is an important area of research due to the long-term applicability of eLearning, within the field of nursing education and nursing research.

Theoretical Framework

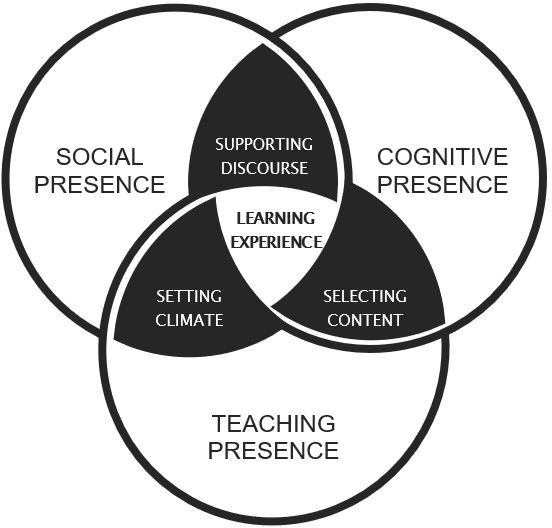

The framework used in this case study is the “community of inquiry” model developed by Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (1999). This model was constructed to identify elements, and their interrelationships, that are important prerequisites required to provide a successful higher educational experience. The theoretical framework assumes that learning occurs within the community based on the interactions of three components: cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence (Figure 1). Cognitive presence is the extent to which learners can build meaning through communication. Social presence is defined as the learner’s ability to express their personal characteristics to other learners. Lastly, teaching presence consists of two general functions: (1) design of the educational process and (2) facilitation of the educational process.

Figure 1 Community of Inquiry Framework (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000).

Method

Aim

The aim of this case study was to explore the experiences of a nursing cohort’s online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

The case study was conducted using a descriptive qualitative approach to explore the experiences of a nursing cohort’s online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anonymous questionnaires administered on KPU’s learning management system (LMS) platform permitted the interviewers to ask questions pertaining to a nursing cohort’s experiences with communication, comradery and comprehension during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Setting

The Faculty of Health at KPU offers a 27-month (seven semesters) advanced-entry second-degree nursing program with approximately 40 students in each cohort. The program consists of both theoretical and practical courses covering foci such as medical and surgical

nursing, mental health, geriatric nursing, pediatric nursing, community health, and global health. Traditionally the semester 1 students meet together face to face during a two-week, on-campus residency course. However, due to COVID-19 restrictions, this year the course was entirely remote except for one four-hour lab in which the cohort was sub-divided into groups of seven or eight students, with each group attending lab on their designated time and day only.

Sample

The research question was intended to study the nursing cohort’s online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. To explore the research question, a convenience sample was used. The sample inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) first-year student in the advanced entry program, (2) registered in the fall 2020 Research course and (3) willingness to participate in the study. Out of the recruited nine students, eight contributed to the study.

Boundaries

The study focused on the nursing cohort admitted to the Fall 2020 intake of the program. Within the program, most of the courses are offered in a hybrid or blended course format through residencies at KPU, practice within health care agencies and communities, combined with distributed or online learning formats. A boundary was set by limiting the scope of the investigation to a specific group of students, who were enrolled in the program’s fall 2020 research course. This boundary was set in order to get ample participants within the limited time to perform the study, as well as, to investigate how their already existing online learning format has been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data collection

To obtain data from the convenience sample, an online open-ended questionnaire was set up on the research course LMS platform. Primarily, data collection had minimal physical and mental health risk due to the avoidance of direct contact with participants and the input of the questionnaire being on an online platform. The potential risk, although miniscule, was whether the participants would have internet access (which was not seen in the results, as most of the participants contributed). The questionnaire was released and intended to be completed on a voluntary basis. There was a total of nine open-ended questions, categorized according to three concepts: communication, comradery and comprehension of the curriculum (Table 1). For each concept there was a broad question and two follow-up prompts to elicit further information. Participants were first given the online consent form via the LMS platform to review and sign.

Afterwards, access to the questionnaire was granted. The questionnaire was open for access on the LMS platform for one week. Questionnaires were made available to nine participants, of which eight participants responded. Once the data was received, an analysis was done.

Table 1: Contents of the open-ended questionnaire administered on the LMS platform

| Communication Broad: How has your ability to communicate with peers and instructors changed due to the online nature of the program? Follow up 1: How has communicating online affected the quality of your communication with instructors and peers? (i.e. lack of body language, tone of voice etc.) Follow up 2: Due to COVID-19 restrictions, how has the amount of communication between you and your peers and instructors been affected? |

| Comradery Broad: During the global pandemic, in what way has your ability to form connections with your peers in the nursing program changed or been impacted? Follow up 1: How did you connect with your peers outside of scheduled seminars and what topics did you include in your conversations? Follow up 2: Have your social interactions increased or decreased as a result of COVID-19 and how has that affected your ability to collaborate with your peers online? |

| Comprehension Broad: In what way has the pandemic impacted your practical skills in the nursing program due to the reduction of in person learning time? Follow up 1: What problems did you face because of the limited entry to the KPU learning spaces during COVID-19 pandemic? E.g. library and lab Follow up 2: Due to the restrictions put in place as a result of the pandemic, in what ways did you practice your skills or competencies related to physical assessments? |

Data Analysis

The questionnaire responses were grouped by question. Each interviewer was responsible for analyzing the responses to one question and identified any recurrent themes. The frequency of communication apps mentioned was recorded.

Ethical Considerations

This study has no known minor or major social, behavioural, psychological, physical, or economic harms to participants or others to disclose. The participation of the cohort was voluntary, anonymous and online, therefore there were minimal/no known discomforts or inconvenience effects. Written consent was obtained from each participant. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. An Ethics Board Application was approved by the KPU Research Ethics Board. All interviewers completed the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans Course on Research Ethics (TCPS 2: Core) prior to beginning the study.

Results

This study focused on examining eight nursing students’ perspectives to explore the experiences of a nursing cohort’s online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. All participants self-reported and were from the same nursing program. Within this realm, there was a special interest in understanding the communication, comradery and comprehension of the curriculum during the global pandemic. The major themes identified from the data analysis were:

(1) communication is challenged and limited during the global pandemic, (2) connection building is limited and altered due to COVID-19 restrictions and (3) performing and building practical skills is restricted due to COVID-19 (Figure 2). As we discussed these themes, we incorporated summaries and quotes from the participants to build the narrative.

Figure 2: Themes pertaining to the nursing cohort’s experiences with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Theme 1: Communication is challenged and limited during the global pandemic

The participants stated that their ability to communicate with their peers and instructors has been limited and altered due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The most noted change was the

restriction regarding no face-to-face interactions with their peers and instructors. They indicated that with reduced opportunities to spend time together in person, they relied heavily on digital communication platforms like WhatsApp, BigBlueButton, Adobe Spark, Google Docs, and through exchanging emails. Due to these alterations with digital means, participants had to wait for several hours to get responses from faculty; whereas in-person interactions were more instant and effective. For example:

“I feel it is more challenging to connect with instructors since email is the primary mode of communication, which has its limitations. Writing an email requires clearly articulating your thoughts into words, whereas an actual conversation allows for spontaneity in responses. Sending an email also means that you have to wait for a response, which can take up to 48 hours or even longer. If this took place in-person, the response would be received immediately.”

However, a limited number of participants stated they had no issues regarding communication challenges due to the global pandemic: For example:

“My ability to communicate with my teachers has not changed because I still email them as I did before.”

and

“Communication with peers has been consistent with the use of groups on media platforms such as WhatsApp, BigBlueButton, Adobe Spark, and Google Docs. Communication from the instructor has been strictly through email with no live discussion used.”

Many participants expressed that their ways of interactions with other students had been altered due to the global pandemic. They emphasized their fear of being misinterpreted while communicating digitally with their peers and faculty. They indicated that online communication eliminates the benefit of seeing certain aspects of body language, critical facial cues, voice tone and ability to convey emotions. Some participants revealed that the only way of communicating with their instructors is through emails. They found it challenging when asking questions, as they were unable to articulate their thoughts into words and sometimes received confusing responses from faculty. Some participants explained that digital communication methods also caused miscommunication and misinterpretation with fellow students:

“Instant messaging with peers can also be challenging in that messages can be misinterpreted by the reader without additional communication aspects such as body language and tone of voice. I have experienced an instance where a fellow student apologized to me for something which I felt was completely unnecessary as I was not upset or angry with this person, but my message had been misinterpreted by the reader such that they felt that there was a conflict occurring between us.”

and

“I write very cautiously and worry about how others can interpret my message later. However, there are some good benefits in this online program. Since we are set to be more active on online forums thanks to technologies and time flexibility for responding, sometimes attempting communications may be easier, but delivering the exact messages to others is challenging without facial expression, tone of voice, and body language.”

These participants expressed that due to COVID-19 restrictions, online communication has been increased compared to in-person, face-to-face communication. This method of communication has also increased with peers due to limitations on other ways of interaction between peers and instructors since the global pandemic.

Theme 2: Connection building is limited and altered due to COVID-19 restrictions

Several participants indicated that they had difficulty getting to know their fellow peers due to the online delivery of the program and consequential inability to meet in person due to COVID-19 restrictions. Various methods were used by participants to connect outside of seminars such as FaceTime, WhatsApp, BigBlueButton, Zoom, Google chat, phone calls and messenger. Some expressed their concern for recognizing people due to the lack of face-to-face contact. Due to the restrictions, it took some participants longer to develop relationships with other students which hindered the ability to form stronger bonds. For example, one participant expressed:

“I don’t get to recognize people easily, as we do not have many chances for face to face interactions.”

and

“It makes it difficult to develop genuine connections and friendships, but they develop nevertheless. The use of technology just may mean that it will take longer for us all to get to know one another.”

Participants expressed that group projects and technology such as WhatsApp have helped facilitate relationships where they were able to have decent communication; answering questions and sharing their personal lives:

“Outside of seminars, I connected with my peers using BBB practice classroom to complete presentations or HREPs together. Also, I use WhatsApp a lot to talk to my peers. We talk about the program and how we are managing the workload, stress, and we also share any study tips/resources we found useful with one another.”

and

“Sharing stories about our families, friends, and significant others.”

Other participants expressed they communicated regarding their emotional distress with peers. Some participant examples include:

“Most of my communication with other students has been done via WhatsApp. We have discussed what we do for work, where we completed our previous degree, thoughts about the program, and exchanged questions about assignments. There are a few students who I have engaged in more personal conversations with, sharing stories about our families, friends, and significant others.”

and

“How we are managing with the workload, stress, and we also share any study tips/resources we found useful with one another.”

and

“I shared my academic concerns such as information about homework and anxiety due to homework with my peers. I talk to them often for group assignments on messenger.”

In-person social interactions have been reduced as reported by the majority of participants, while virtual social interactions have increased. As a result of increased virtual social interactions, participants’ abilities to collaborate with peers online have not been negatively affected. Some participants report their ability to collaborate with peers online have actually been strengthened:

“One of the positive aspects of transitioning to online communication during the pandemic is that I am now more knowledgeable with video conferencing platforms such as Zoom and have used those skills to assist communication and teamwork with peers.”

and

“I think they have increased because I have never communicated more with a group than I do now.”

Many participants have found it more difficult to form connections with their fellow peers due to the COVID-19 restrictions. Due to the restrictions, meeting in person is no longer an option due to the current COVID-19 situation. The global pandemic has increased participants’ use of virtual social interactions while limiting in-person interactions. It was harder to connect and build relationships due to the lack of face to face contact. Group projects have been credited by many participants for helping to facilitate relationships to help develop bonds. Although it is more difficult to establish relationships, it is possible through alternative methods.

Theme 3: Performing and building practical skills is restricted due to COVID-19

The participants indicated that their practical skills were negatively impacted due to the lack of in person hands-on learning caused by the COVID-19 restrictions. For example, a participant said:

“There is a reduction of hands-on learning which I feel hinders us and impacts our skills.”

Another participant voiced challenges related to limited entry into learning spaces due to COVID-19 restrictions which caused uncertainty around expectations, and limited confidence with their clinical skills:

“Without lab, I feel like I don’t have a strong foundation of the practical skills I’ve read about. Without having a lab instructor to provide feedback, or correct me, I feel as if I do not know if what I am doing is right or wrong. Also, without testing my skills, it is hard to tell what I’ve learned and what I need to improve on.”

and

“There has not been enough lab to practice my skills.”

Due to these restrictions, several participants addressed the decreased feedback, lack of social and instructor support related to limited in person contact for labs, and less accessible library hours, and uncertainty around correctness of clinical skills. Some participants expressed the following examples of how this caused them emotional distress:

“Learning hands-on skills in the lab is greatly impacted and it gives me anxiety.”

and

“I do worry about my ability to do basic tasks like making a bed and peri-care. I know that I will develop those skills eventually but in the short term I am afraid of nurses getting impatient and angry with me in clinical.”

These restrictions have caused many participants to search for alternative online methods to build their practical skills and indicate the challenges they have encountered due to these alterations. For example, practising hands-on skills or competencies related to physical assessment has decreased on real patients as evidenced by:

“I used YouTube videos to learn skills and I use additional textbooks and online resources to complement what I need to learn skills.”

These participants expressed the struggles they faced while trying to maintain a professional practice in an unprofessional setting. Other participants echoed this statement of practice in informal settings:

“I practised my physical assessment skills (such as head-to-toe) on my family, coworkers, and friends who are within my bubble.”

and

“I practised physical assessments on my family members who did not always take me seriously.”

and

“I used these assessments on family members which I don’t feel gave me the full effect of learning.”

Many participants also indicated their increased reliance on videos to aid in their hands-on development. For example, a participant explained these resources did not equip them with adequate skills that they will need to implement in real world settings.

“I am spending a copious amount of my time watching YouTube videos and practising the skills I’ve learned on my family members. Due to this, my practical skills may not reflect a real situation.”

Participants expressed their challenges with the limited accessibility of the lab facility being available for practice, where many participants had to search for alternative ways to practice their skills. This brought its own limitations such as forcing students to situate within their bubble to adhere to COVID-19 restrictions which limited the amount of people they were able to practice their skills on, and a heavy reliance on videos to learn their hands on skills. Many indicated these limitations brought uncertainty with expectations as these alterations and restrictions hindered their practical skills to prepare for real world settings and caused great emotional distress.

Discussion

This case study sought to reveal the experiences of nursing students in regard to communication, comradery, and comprehension of the curriculum within their cohort

during the COVID-19 pandemic. The major findings were that students reported feeling challenged in their ability to communicate and connect with one another and with the faculty, and that their ability to practice and build on practical clinical skills was limited due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

The COVID-19 pandemic placed restrictions on gatherings and building access, thus the KPU campus and its learning facilities were closed to the students. Students did not meet each other until their four-hour lab, and then they were subdivided into groups of eight.

They were further divided into groups of six for their clinical placements, thus they have never fully met all the members of their cohort during their first year. The pandemic restrictions were a physical barrier to connection between the students.

In lieu of physical communication, digital communication platforms such as WhatsApp, Google Docs, BigBlueButton, Adobe Spark, and email were heavily utilized for communication between students. This communication was often asynchronous and lacked the emotional aspect of communication that facilitates connection. Students reported frustration with having to wait for a response to a query from their instructors or peers, which affected the continuity and cohesiveness of learning. Students also reported challenges in getting comprehensive clarification from faculty over email, as they were unable to fully articulate their thoughts and follow-up concerns, resulting in inadequate and often vague explanations from the faculty in return. Synchronous digital platforms such as BigBlueButton and Zoom (video calling) were used less frequently, and their use was limited for collaboration during group projects and during instructor-led seminars. While these communication platforms were primarily video based, allowing tone inflections and body language to be seen and interpreted on the other end, its consistent use is not a practical solution to the communication concerns previously mentioned due to scheduling conflicts. As the nature of the nursing program is primarily asynchronous with very few mandatory scheduled seminars, all the students are working on their own schedules around their home and social lives, thus making synchronous communication an inherent challenge in the program’s execution.

Digital communication concerns also centred on the fear of being misinterpreted in their communications. Online messaging eliminates the nonverbal aspects of communication, such as body language and tone inflection. Since these students had never met, intercommunications were rigid and formal at first because there was no baseline for how they could behave or what level of banter was appropriate. One student reported experiencing a miscommunication in which another student messaged them to apologize for something that the first student felt did not warrant an apology, but their original response had been interpreted by the other student as if there was a conflict between them. Texts are easily misinterpreted, thus the reliance on digital communication between the students during this pandemic further hindered the ability to connect and understand each other, resulting in a lack of comradery among the group.

The pandemic has also heavily limited the first-year nursing cohort’s ability to physically practice the clinical skills necessary for their future profession. The closure of the Nursing Lab facilities found the students supplementing their theoretical curriculum with YouTube videos, and the evaluations of their skills were through peer-evaluations of home-made videos filmed on members of their home or “social bubble”. Participants largely expressed insecurity in their skills as a result of this incomprehensive training, further reinforcing the negative impact the pandemic restrictions have placed on the learning experience of this nursing cohort.

One positive that has come out of this online experience is that some students expressed that the online delivery of the program has forced them to advance their technology skills. Due to the second-degree nature of the nursing program, some students have been out in the field working in their respective disciplines before entering the program, so their daily interactions and necessity for the use of collaborative academic technologies had declined. At the beginning of the program, when it was learned that there would be a heavier emphasis on the use of educational tools and collaborative technology, these students expressed concern for their ability to keep up with all the new apps. However, as the COVID-19 health mandates have restricted the program delivery to the virtual classroom, a positive outcome is that through peer support and lack of no other choice but to succeed, these students reported increased comfort with using technology to learn with and from each other.

All three themes identified in this study can be associated with Garrison, Anderson and Archer’s Community of Inquiry Framework model. This theoretical framework emphasizes the importance of social presence, teaching presence and cognitive presence in facilitating a successful higher educational experience. The social presence is embodied in the students’ use of communication apps to connect with each other virtually. The teaching presence is evident in the peer-evaluations and peer support in learning the material through collaboration. The cognitive presence is perpetual within each student as they navigate a learning experience unlike any other experience they have worked through before. While the COVID-19 pandemic has altered traditional aspects of the higher educational learning experience, this cohort has resourcefully utilized the available school-provided resources in combination with each other’s knowledge and experiences in relation to the three “presences” conceptualized from the Community of Inquiry theoretical framework.

This study analyzed the qualitative experiences of a unique cohort of nursing students, with the aim of understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected them in three theme areas. There were several limitations of the study that affected the transferability of the findings beyond the scope of this specific cohort: the small sample size, and limited data pool. The sample size of participants was eight, which is not enough to extrapolate for general nursing students outside of this program, and therefore limits the transferability of the study. Secondly, there was not a lot of data collected; only nine open-ended questions were asked in total: three main questions for each of the three aspects of interest (communication, comradery, and comprehension), and two follow-up questions for each topic. The questions were asked anonymously without a chance for further follow-up to enrich the data pool. Data saturation was not reached, so the results may be oversimplified. Furthermore, due to the anonymous, compartmentalized execution of the data collection, rich details such as participant emotion and body language when conveying their responses were lost. Open-ended interviews in a focus group would have yielded richer data, however, these limitations were also a result of the COVID-19 restrictions on gatherings, thus inherently captures the essence of the struggles students and researchers are currently experiencing globally.

Conclusion

Technology can bring us together and simultaneously isolate us from our community.

Our goal in exploring the topic of online study during a global pandemic was to understand how increasing health mandates and restrictions play into themes of connection and disconnection resulting from communicating and learning almost exclusively online. During the first term of this fall 2020 cohort’s education, communication and connection were severely limited for most study participants as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Three main tenets of

limitation emerged as a result of a thematic analysis of cohort study participants: (1) communication was challenging and limited, (2) the physical restrictions mandated by the COVID-19 pandemic response altered connection building, and (3) practical clinical skill building and practice was hindered. Through obtaining data regarding the experiences of nursing students from the fall 2020 cohort of students, we were able to better understand what effect the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the communication, comradery, and comprehension of online learning. Our descriptive qualitative study of a convenience sample of eight students differs from the majority of studies examining online learning, as previous studies have focused on positive perceptions of convenience and flexibility or negative perceptions, such as inadequate access to a computer, insufficient skills, or lack of time. Our case study provides a unique perspective, in that it exposes the impact between online learning and the effects of a global pandemic on the experience of nursing students, who were otherwise prepared to engage in full-time study online.

Relevance for clinical practice

These findings have a few practice implications. Firstly, understanding that communication was challenging and limited gives insight for faculty to encourage communication and aid students in finding ways to effectively communicate online. Starting a thread in the online discussion boards for questions from faculty provides greater transparency in explanations regarding assignments, ensuring that all students will have access to the same advice, feedback, and explanations. This strategy can help students that start assignments later, reducing the chance of getting repeat questions or worrying about not getting clarification in time. Having all the information in one accessible and collaborative space would support student comprehension of the material, as well as prevent the faculty from having to repeat themselves to many different students that email similar questions.

Secondly, the physical restrictions mandated by the COVID-19 pandemic response limited the students’ abilities to practice nursing skills in a lab or classroom setting. Faculty can aid in student’s learning by making up this lab time with creative ways students can safely practice together and get feedback from the instructors on the physical clinical skills.

Limitations of the study

In this study, the sample size of eight participants who completed the online questionnaire is a small sample size. This limits the generalizability of this study. Another limitation is that data was collected from first semester nursing students in one program, thus findings may be more specific to this population. Findings may not be transferable to all nursing students’ online learning experiences.

Implications for future research

The current study recommends further research on how to promote effective communication in an online, asynchronous learning environment in order to develop a sense of comradery between students who have never met in person. Exploring factors that would engage and encourage students is highly recommended in order to develop a curriculum that caters to the unique clinical needs of an online nursing program. It is important to consider how effective online learning is regarding comprehension of both theoretical and practical skills required of nursing students.

References

Ali, N. S., Carlton, K. H., & Ryan, M. (2004). Students’ perceptions of online learning: Implications for teaching. Nurse Educator, 29(3), 111-115.

Atack. L. (2003, October 20). Becoming a web-based learner: registered nurses’ experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(3), 289-297. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02804

Atack, L., & Rankin, J. (2002, November 4). A descriptive study of registered nurses’ experiences with web-based learning. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40(4), 457-465. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02394

Garrison, R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

George, P .P., Papachristou, N., Belisario, J. M., Wang, W., Wark, P., Cotic, Z., Rasmussen, K., Sluiter, R., Riboli-Sasco, E., Car, L. T., Musulanov, E. M., Molina, J. A., Heng, B. H., Zhang, Y., Wheeler, E. L., Shorbaji, N. A., Majeed, A., & Car, J. (2014, June). Online eLearning for undergraduates in health professions: A systematic review of the impact on knowledge, skills, attitudes, and satisfaction. Journal of Global Health, 4(1). doi: 10.7189/jogh.04.010406

Gerkin, K., Taylor, T., & Weatherby, F. (2009). The Perception of Learning and Satisfaction of Nurses in the Online Environment. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 25(1), E8-E13.

Guri-Rosenblit, S., & Gros, B. (2011). E-Learning: Confusing Terminology, Research Gaps and Inherent Challenges. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 25(1). Special section p. 1-12.

Holly, C. (2009, September). The Case for Distance Education in Nursing. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 5(3), 506-510.

Kemp, N., & Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates’ opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Frontiers in Psychology, (5) Article 1278. doi: 10.3389/fpsy.g.2014.01278

Kentnor, H. (2015). Distance Education and the Evolution of Online Learning in the United States. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, 17(1&2), 21-34.

Kim, S. (2006). The Future of e-Learning in Medical Education: Current Trend and Future Opportunity. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 3, 3. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2006.3.3

Masic, I. (2008). E-learning as new method of medical education. Acta Informatica Medica, 16(2), 102-117. doi: 10.5455/aim.2008.16.102-117

Nguyen, T. (2015). The Effectiveness of Online Learning: Beyond No Significant Difference and Future Horizons. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 11(2), 309-319.

Pei, L., & Wu, H. (2019). Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education Online, 24(1). doi: 10.1080/10872981.2019.1666538

Sener, J. (2012). The seven futures of American education: Improving learning and teaching in a screen captured world. CreateSpace

Vaona, A., Banzi, R, Kwag, K., Rigon, G., Cereda, D., Pecoraro, V., Tramacere, I., & Moja, L. (2018, January 21). E-learning for health professionals. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, (1)1. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011736