Best Practices in Training Nurses to Use Electronic Health Records: A Literature Review

By Jennifer Wilks, MHS

Regional Manager, Clinical Education, Vancouver Coastal Health

Citation: Wilks, J. (2025). Best practices in training nurses to use electronic health records: A literature review. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 20(1). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=14284

Abstract

Electronic health records (EHRs), now commonplace in hospital environments, can improve patient care as compared to paper-based charting systems. Training staff, particularly nurses, to use EHRs correctly and efficiently is an essential component of implementing these systems successfully. This paper summarizes research on nurse EHR training approaches that are outside traditional instructor-led classroom training including e-learning, simulation, and peer mentoring/coaching, using the Kirkpatrick Model of training evaluation as a framework to present the strengths of each modality. It outlines how an organization’s choice of training model impacts nurse confidence in using these systems, and how multiple training modalities can work in combination, with current trends favouring a multi-modal training approach. Additional considerations including timing of training, today’s new graduate nurses, and change management are discussed. Limitations and suggestions for future study include a lack of evidence linking training modalities to Kirkpatrick Level 4.

Overview

An electronic health record (EHR) digitizes a patient’s medical chart information, including problems, medications, vital signs, and medical history, along with lab, radiology, and other reports (Boothe et al., 2020). Replacing physical paper charts with an electronic system allows all relevant healthcare providers to access complete information about their patients, thereby preventing errors and increasing accessibility (Ministry of Health Services BC, 2009). The shift associated with EHRs goes beyond simply eliminating paper; it integrates disparate systems and transforms the way clinicians work (National Learning Consortium, 2013). Digitizing patient care is not without its challenges however, and moving from a paper-based system to an EHR represents a substantial change management project at the organizational level. A lack of or inappropriate training is one of the significant challenges surrounding implementation of EHRs (Topaz et al., 2017), and information provided to healthcare staff on when, where, and how to use them is essential because of the links between clinician use of EHRs and clinical outcomes (Bowman, 2013; Bredfeldt et al., 2013; Samadbeik et al., 2020; Ting et al., 2021). This paper summarizes research on approaches used for training nurses on using EHRs that are outside traditional instructor-led classroom training, including e-learning, simulation, and mentoring or coaching, and how these modalities can be used in combination. When educating nurses on using EHRs, the training model chosen by organizations directly impacts nurse confidence in using these tools, and current trends indicate that multi-modal training approaches are favoured over any single training modality alone.

Background

Electronic Health Records in Canada

Canada has been undergoing a transformation to digital healthcare since the 1990s, when hybrid use of paper and electronic charts became commonplace (Boothe et al., 2020; Evans, 2016). EHRs benefit not only individual patients, but organizations, and society at large. An early study showed that simply eliminating the problem of illegible handwritten orders at a large tertiary care hospital contributed to reducing serious medication errors by more than half (Bates et al., 1998). Organizational outcomes can include improved operational performance when fewer redundant tests are ordered, and there is no longer a need to manually distribute results to various clinicians (Menachemi & Collum, 2011). Society benefits through the volume and quality of population health data EHRs are able to collect, and the potential uses for this data in research (Boothe et al., 2020; Menachemi & Collum, 2011). EHRs support not only individual patient outcomes, but broader population health improvements (Menachemi & Collum, 2011), making them a critical component of health services in the 21st century.

Registered Nurses and EHRs

From admission to discharge, nurses in hospitals with an EHR system use it to document all aspects of the care they provide. This includes not just the obvious nursing activities, such as administering medications or completing patient assessments, but a wide range of other information. Depending on the setting and expectations, nurses might be required to document everything from a description of a patient’s personal belongings to the volume and consistency of each bowel movement. The proportion of time nurses spend documenting during each shift has been reported as ranging from 28.3% (Roumeliotis et al., 2018) to as high as 40% (McBride et al., 2023). The systems themselves can vary in terms of useability and are sometimes designed with little consideration for the workflow and environment in which they will be used (Kellogg et al., 2017). The practical useability (or lack thereof) designed into an EHR and the burden of documenting is associated with nurse burnout (Alobayli et al., 2023; Gesner et al., 2019) and moral distress (McBride et al., 2023), at a time when systems in Canada and globally are experiencing critical shortages of nurses (Baumann & Crea-Arsenio, 2023). This is leading some organizations to focus quality improvement projects on reducing this burden (Donohue-Ryan et al., 2023).

Still, nurses generally understand that computer technology improves nursing practice and promotes quality care (Duffy, 2015; Tsarfati & Cojocaru, 2022). Training has a significant impact on how EHR systems are used and the overall success of implementing them (Kinnunen et al., 2019), and effective training programs have been shown to increase documentation efficiency and confidence (McBride & Tietze, 2023). Nurses who are satisfied with both the usability of their hospital’s system and the training provided are more likely to report confidence in using an EHR (Canada Health Infoway, 2017). Conversely, inadequate training can prevent nurses from using EHRs effectively (Abu Raddaha, 2017). A 2017 national survey found that just 15% of Canadian nurses were highly satisfied with the training that was provided to them on their EHR systems (Canada Health Infoway, 2017). Additional stressors (e.g., COVID-19) can further intensify frustration with the EHR, while impacting the access to needed supports (Rucci et al., 2023). The proportion of time spent using these tools, and the impact they can have on both the patient and staff experience, underscore the importance of effective training paradigms; training that prepares nurses to not only meet documentation expectations, but meet them while providing high quality patient care.

Kirkpatrick Model: A Framework for Evaluation

A useful framework when considering the effectiveness of training modalities is the Kirkpatrick Model of training evaluation, which was developed in the 1950s and is applicable across a variety of industries (Kirkpatrick Partners, 2024). It consists of four levels for measuring the success of any training program:

Level 1, Reaction. How did participants react to the training? Were they satisfied with it?

Level 2, Learning. Did the training result in an increase in knowledge or skills?

Level 3, Behaviour. Did the training result in a change in behaviour at work? Are participants using what they learned?

Level 4, Results. Did the training result in a positive impact on the business or organization? (Kirkpatrick Partners, 2024; Kurt, 2018).

Leaders implementing EHR training programs for nurses intend for training to impact Behaviour (Level 3); i.e., that teaching EHR best practices will lead nurses to use these practices in their day-to-day work. Doing so successfully should then impact organizational Results (Level 4) by contributing to improved patient care, an ultimate goal of the EHR implementation. It is important to note however that if the only method evaluating the success of a training program is a post-training satisfaction survey, this is a Level 1 evaluation under the Kirkpatrick Model and is not necessarily indicative of a behaviour change. Similarly, a knowledge or skill post-test would only be measuring Level 2 by demonstrating the retention of knowledge and does not prove the nurse has changed their practice or behaviour. Considering research on training models through this lens is a useful way to compare and contrast their effectiveness.

Search Strategy

The literature search for this paper was limited to peer-reviewed content in databases including CINAHL Plus, MEDLINE, and Academic Search Complete, available in full text in English. Studies from 2014 to 2024 that included an evaluation of an EHR training approach were included, including both qualitative and quantitative original research and reviews. Articles over 10 years old were excluded for this section, as the topic relates to quickly evolving technology. Search terms included nurse OR nurses OR nursing AND “electronic health record” OR EHR AND training OR education. This yielded 595 records, the majority of which, while referring to training, were not measuring a specific training method. Fifteen relevant articles were found that focused on evaluating one or more training method used to prepare frontline nurses for an EHR implementation.

Results

EHR Training Models

Traditional models of EHR training often involve a focus on functionality, taught in a classroom or computer lab setting by trainers who may not have a clinical background or knowledge of nurse workflows (Olley & Hozynka, 2023). The following section describes three training modalities that have been used both on their own, or to build on or replace traditional classroom or computer lab training to influence learner Reactions (Level 1), Knowledge (Level 2), and Behaviour (Level 3).

E-Learning

The use of e-learning in nurse continuing education is becoming increasingly prevalent (Rouleau et al., 2019). In general, studies have shown that using e-learning yields similar outcomes to classroom training (Rouleau et al., 2019), and may be particularly suitable in cases where nurses are coming with existing experience and may benefit from a self-paced format (Smailes et al., 2019). Smailes et al. (2019) evaluated the switch from traditional instructor-based classroom learning to an e-learning model for nurse EHR training at a large US academic medical centre. Learners with experience using EHRs were able to move faster through the e-learning content, and others who were less familiar could take additional time; this contributed to both learner satisfaction and overall efficiency of training. The researchers found the shift provided advantages such as flexibility, convenience, and an overall reduction in training time compared to instructor-led training, and that instructor-led training took up to 50% longer to achieve the same results.

The disadvantages of e-learning included little or no contact with instructors, and potential problems with technology use if learners the lack necessary computer skills to begin with (Bahrambeygi et al., 2019). Using the Kirkpatrick model, a systematic review by Rouleau et al. (2019) indicated that while the majority of studies show the positive impact of e-learning surrounding Level 1 (Reaction) and Level 2 (Knowledge), little information is available to show e-learning’s effect on practice change (Level 3) or patient outcomes (Level 4).

Simulation

Simulation-based learning refers to replacing real patient interactions with scenarios that allow learners to consolidate skills and knowledge by practicing them in a safe, but realistic, environment that allows for feedback between educators and learners (Koukourikos et al., 2021). This could include the use of mannequins, task simulators, computer-generated simulations, or standardized patients played by actors, and helps address limitations related to availability of clinical learning experiences with real patients (Koukourikos et al., 2021).

Research has shown positive outcomes from incorporating simulation in EHR training. Vuk et al. (2017) examined an interprofessional EHR education program in which physicians and nurses simulated a patient encounter while using a training version of the EHR to access test results, manage orders, and write notes. The researchers found significant increases in reported self-confidence by the clinicians in using the EHR following the simulation, again pointing to successful training as per Level 1 (Reaction) and Level 2 (Knowledge) measures. A literature review by Wilbanks and Aroke (2020) found that using clinical simulations in EHR training provided opportunities to examine communication among the interdisciplinary team, resulting in sustained behavioural changes that translated into practice; this is one of the few articles showing evidence of Level 3 (Behaviour) results as per Kirkpatrick’s Model. However, Wilbanks and Aroke (2020) pointed out that simulation requires significant resources to deliver, including equipment, space, and personnel; those developing and leading simulations are often specialists with specific training in simulation education for the health sector, and a simulation laboratory can be cost-prohibitive for smaller organizations.

Mentorship and Coaching

Mentorship and peer-to-peer coaching are fundamental in transitioning to independent practice among many health care professions. Nurses frequently learn informally from each other in-the-moment on shift, as well as from nurse leaders and practice experts in their care area. A grounded theory study by Weinschreider et al. (2024) argued that EHR educators are primarily teaching through modeling the knowledge and skills required when using the EHR. Like other domains of knowledge transfer among nurses, this modeling might occur during hospital or unit orientation in a structured manner or might occur informally over the course of a shift (Weinschreider et al., 2024).

Formal mentorship and coaching programs initiated as a part of an organizational EHR strategy have also been studied. Burgess & Honey (2022) found that using coaches or ‘digital nurse champions’ helped to foster a peer support culture, and that nurses who had regular access to champions felt less pressure and stress. Malane et al. (2019) chronicled the implementation of an ‘ambassador’ program at a large academic health system for a one-year pilot, arguing that having a trainer with relevant clinical experience supported learners as they trained to real workflows, while preventing them from coming up with workarounds. As an added benefit, the program provided experienced nurses with a professional growth opportunity, as mentors were developed into practice leaders. Although no long-term analysis has been published on results from this program design, mentorship is known to impact job retention and satisfaction for nurses more generally (Vlerick et al., 2024). Scandiffio et al. (2024) conducted a scoping review of the mentor-learner relationship in digital technology adoption and found instruction from mentors to be rated highly. The 19 studies they reviewed generally included robust results for Level 1 (Reaction) and Level 2 (Knowledge), though only two could report Level 3 (Behaviour) change. Learners in some studies did not feel they received enough mentor contact, pointing to workforce or operational challenges with executing a coaching training model.

A challenge presented by the mentorship model is that learners can experience confusion with respect to expectations if they are working with different or multiple mentors, potentially resulting in a decline in feeling supported (Weinschreider et al., 2024). Other studies have reported that nurse mentors can experience competing priorities, making it difficult to maintain consistent support; as such dedicated positions are more likely to be successful (Burgess & Honey, 2022).

The Shift to Blended Approaches

Ting et al. (2021) conducted an integrative review of 15 studies from 2010 to 2020 involving education interventions for nurses using an EHR. Their review indicated a shift towards blended approaches, including a mix of e-learning and peer coaching, and away from didactic classroom training during this time. The studies included reported positive outcomes with respect to learner satisfaction and confidence when multi-pronged education approaches were used, and when workflow-based scenarios reflecting daily routines were used in training. This validates an earlier scoping review by Younge et al. (2015) suggesting that, while there may not be a consensus as to what method is best, combining training methods is a more effective strategy than using one method alone.

There are a number of ways in which multiple training modalities can be structured into a coherent training plan. In one example, Mohan et al. (2021) proposed a four-level blended model, beginning with basic computer skills training followed by increasingly specific levels of simulation-based EHR training specific to a clinician’s care area, complimented by one-on-one training. Mohan et al. suggested moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and proposed an algorithm to determine which level of training each learner needed depending on their previous experience both with an EHR and with the organization. This points to the possibility of creating learner-driven pathways, with clinicians selecting education that meets their individual learning needs.

While evidence points to the benefits of integrating learning modalities, doing so must be done thoughtfully and purposefully. Wilbanks et al. (2018) cautioned that if techniques such as a simulation are used too early with clinicians who are new to using the EHR, learners could be overly focused on learning the basics of the EHR system rather than gaining the benefit of the simulation.

Discussion

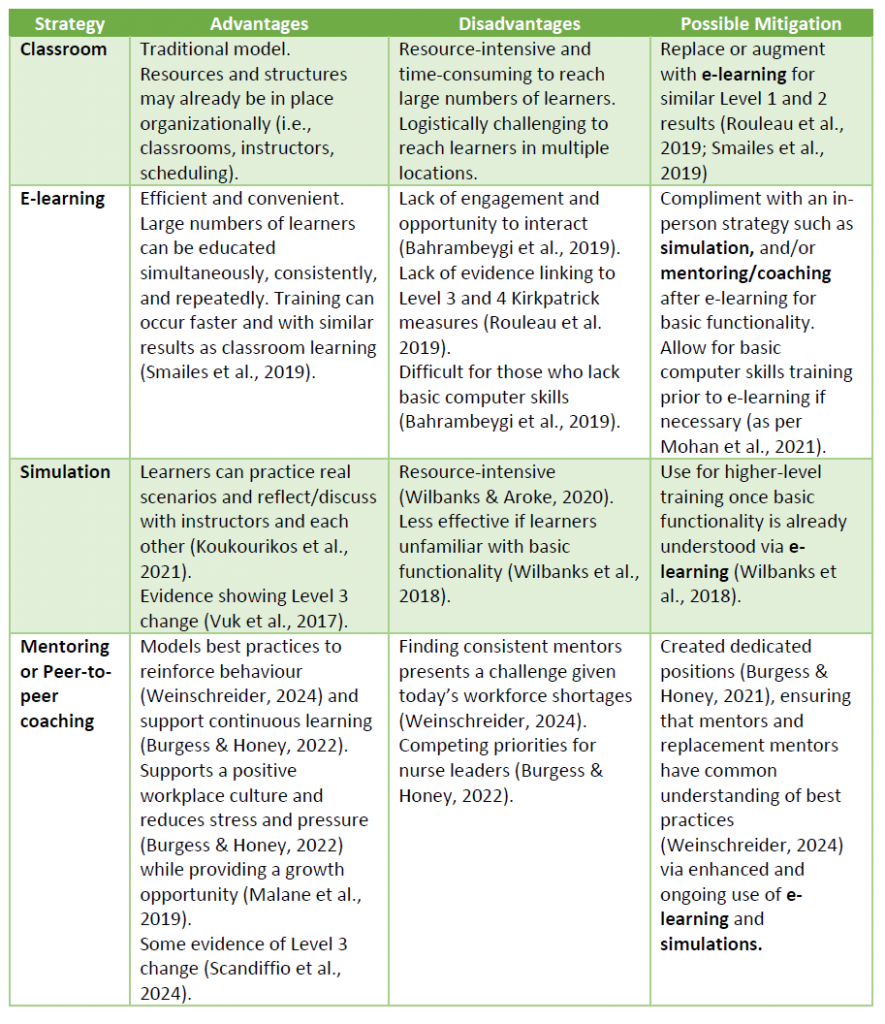

Each of the modalities discussed presents advantages. E-learning can be used in a standardized manner across different geographic locations at a learner-defined pace, providing convenience to learners while being more efficient than traditional instructor-led learning. In the context of EHR training, e-learning could take a variety of forms including interactive modules, videos, and/or independent practice in a training version of an EHR system. Simulation allows learners to practice scenarios reflecting what they will experience in their care area, while providing opportunities for discussion and reflection with each other and instructors. Practicing documentation activities alongside nursing skills (e.g., completing a head-to-toe assessment) via simulation provides an experience closer to real patient care, in which documentation is not a standalone activity, but is embedded across nursing practices. Mentoring and peer-to-peer coaching allow for ongoing reinforcement of best practices in the actual setting in which nurses are working, while making a positive contribution to workplace culture. In isolation however, each of these approaches also brings potential drawbacks. These pros and cons are summarized in Table 1, along with options for mitigation of disadvantages.

Table 1

Summary of EHR Training Strategy Advantages, Disadvantages, and Possible Mitigation

It is evident in Table 1 that mitigating the disadvantages of any one strategy likely involves employing another. Based on the literature, Figure 1 below presents a possible approach for layering multiple training modalities.

Figure 1

Example of a Multi-Modal EHR Training Strategy

The Figure 1 example begins in the weeks leading up to implementation. At this time, learners needing support with basic computer skills can begin gaining comfort with technology (0) prior to learning about the EHR. Those already comfortable with technology can begin EHR e-learning (1) via self-directed modules. This e-learning would enable standard learning objectives to be met by a variety of learners in multiple locations at their own pace (advantage), influencing Level 1 and Level 2 indicators as per Kirkpatrick’s model. Though they may not be able to ask questions during e-learning (disadvantage), it could be followed by practicing short, facilitated simulations (2) of common workflows in their care area as the implementation approaches. Walking through a simple head-to-toe assessment using simulated patient data and real equipment could build confidence while allowing team members to ask questions (advantage) and supporting Level 3 indicators. There may be resource challenges in running large volumes of repeated practice simulations (disadvantage). However, once the system is live, dedicated peer coaches who were previously trained could be assigned to units (3). While e-learning and simulation focused on general training for day-to-day workflows, in this phase coaches could now support unit-specific best practices (advantage) and help navigate novel situations in real time as the nurses gain competence and confidence. If coaches are difficult to keep in place due to workforce challenges or competing priorities (disadvantage), the e-learning and simulations could remain accessible, so new coaches could be trained using these same materials. These three streams of training – e-learning, simulation, and peer coaching – can occur concurrently, and continue beyond implementation as learners determine their own education needs via self-assessment tools. While each of the modalities described has limitations, they can be combined to form a comprehensive training plan.

Additional Considerations

Timing of Training in Relation to Implementation

EHR implementations can be vast projects in which hundreds or thousands of clinicians require education. Logistically, training this volume of individuals presents challenges, lengthening training timelines; however, training staff too early could dilute the effectiveness of the education. Heponiemi et al. (2021) suggested that not only does training need to begin two to three weeks prior to implementation, but it must continue for several weeks after, with ongoing assessment to determine whether or not training is still necessary. This points to the need to build flexibility and responsiveness into a training plan. While only 15% of Canadian nurses surveyed in 2017 reported being highly satisfied with the initial training they received on the EHR, this is higher than the 9% who reported being highly satisfied with the ongoing training available to them afterwards (Canada Health Infoway, 2017). The strategy of peer-to-peer coaching is well suited to ongoing training, as structures such as protected training time and/or dedicated coach positions can be put in place to facilitate ongoing knowledge transfer between nurses.

New Graduate Nurses

Registered nurses graduating today are entering an industry in the midst of an ‘unprecedented workforce crisis’ (Weinschreider et al., 2024, p. 1). While operational leaders might assume that a tech-savvy Generation Y or Z new graduate nurse would easily transition to using an EHR, a 2022 study found that nursing graduates were not consistently prepared for a digital health environment (Kleib et al., 2022). Weinschreider et al. (2022) found new graduate RNs to overestimate their skills in using EHRs, and that being comfortable with technology does not necessarily translate to EHR confidence. Some are looking to academia to begin bridging those gaps earlier in the nurse career journey, arguing that significant reforms in nursing education are required so that basic informatics becomes a competency of nurses entering the workforce (Lentz Maidment, 2024). As documentation competencies become commonplace, there are opportunities for entry-level nursing programs to further integrate electronic health record training so that nurses are more prepared when beginning at a new employer organization.

Change Management Strategy

As an example of the scale of a large EHR project, the Epic system at Mayo Clinic cost $1.5 billion USD to implement and involved thousands of staff who care for tens-of-thousands of patients annually across multiple sites and health sectors (Borgwardt et al., 2019). The way this level of enormous change is managed – change that represents a fundamental shift in the way clinicians work – is critical to its success. In parallel, if the education supporting this change is poorly planned it can lead to negative impacts on nurses when their learning needs are left unmet (Burgess & Honey, 2022). There are multiple steps that should take place concurrently with designing a training plan, including developing the staff engagement plan, identifying site champions, confirming leadership support, and ensuring staff understand the need for the change (Doctors of BC, 2021). Further, if other organizational changes are underway at the same time as an EHR implementation, organizations must be prepared to manage competing demands (Rucci et al., 2023). All change involves learning (Rousseau & ten Have, 2022), and the development of a carefully planned training strategy is one of multiple pillars of change management in this context. While a detailed review of change management frameworks is beyond the scope of this paper, as organizations plan their change strategies and associated resource allocations, they must consider training early on just as they would a communication plan or equipment provision.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Study

Returning to the Kirkpatrick Model, it is important to note that while many studies cited in this paper include Level 1 (Reaction) and Level 2 (Knowledge) measurements, few studies demonstrated behaviour change (Level 3), and none translated their training programs directly to organizational results or patient outcomes (Level 4). This is consistent with Ting et al.’s (2021) findings that EHR training modalities are not clearly linked to patient safety. Ting et al. also highlighted that studies of EHR training generally do not include randomization to different training groups, or rigorous study design. Further, while combining educational modalities will bring challenges associated to resource allocation, little data exists evaluating combined methodologies or measuring the return on investment of different combinations. When designing a training program evaluation, leaders, educators, and researchers should consider ways in which Level 3 and Level 4 change can be measured. This could include longitudinal surveys of learners and supervisors to determine if behaviour change has occurred, and monitoring patient safety indicators such as medication errors over time. Adding this type of data to the literature would support decision makers to make the best possible choices based on evidence, rather than on assumptions about what training is most effective.

Conclusion

EHRs, and nurses who use them, are foundational to supporting the best possible patient outcomes in today’s digital care environment. Several distinct strategies exist for training nurses to use an EHR, including e-learning, simulation, and mentorship or coaching, and each of these strategies come with challenges that can be mitigated by thoughtfully integrating them together. There are limitations in the research, including a lack of evidence linking training models to Kirkpatrick’s Level 4, which should be addressed by future studies. Despite this limitation, a growing body of evidence points to the potential of blending training models, thereby creating a learning journey that prepares nurses to confidently document while providing effective patient care.

References

Abu Raddaha, A. H. (2018). Nurses’ perceptions about and confidence in using an electronic medical record system. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 27(2), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/2010105817732585

Alobayli, F., O’Connor, S., Holloway, A., & Cresswell, K. (2023). Electronic health record stress and burnout among clinicians in hospital settings: A systematic review. Digital Health, 9, 20552076231220241. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231220241

Bahrambeygi, F., Roozbahani, R., Shojaeizadeh, D., Sadeghi, R., Nasiri, S., Ghazanchaei, E., & EhsanMaleki, S. (2019). Evaluation of the effects of E-Learning on nurses’ behavior and knowledge regarding venous thromboembolism. Tanaffos, 18(4), 338–345. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7309888/

Bates, D. W., Leape, L. L., Cullen, D. J., Laird, N., Petersen, L. A., Teich, J. M., Burdick, E., Hickey, M., Kleefield, S., Shea, B., Vander Vliet, M., & Seger, D. L. (1998). Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA, 280(15), 1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.15.1311

Baumann, A., & Crea-Arsenio, M. (2023). The crisis in the nursing labour market: Canadian policy perspectives. Healthcare, 11(13), 1954. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131954

Boothe, C., Bhullar, J., Chahal, N., Chai, A., Hayre, K., Park, M., Ragan, C., Ramirez, C., & Suh, D. (2020). The history of technology in nursing: The implementation of electronic health records in Canadian healthcare settings. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 15(2), 1–10. https://cjni.net/journal/?p=7192

Borgwardt, H. L., Botz, C. T., Doppler, J. M., Elthon, B. I., Hansen, V. P., Jasperson, J. C., Larson Keller, J. J., Martindale-Mathern, S. C., Reinschmidt, K. J., & Shinde, A. S. (2019). Electronic health record implementation: The people side of change. Management in Healthcare: A Peer-Reviewed Journal, 4(1). https://hstalks.com/article/5571/electronic-health-record-implementation-the-people/

Bowman S. (2013). Impact of electronic health record systems on information integrity: Quality and safety implications. Perspectives in Health Information Management, 10(Fall), 1c. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24159271/

Bredfeldt, C. E., Awad, E. B., Joseph, K., & Snyder, M. H. (2013). Training providers: Beyond the basics of electronic health records. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-503

Burgess, J. M., & Honey, M. (2022). Nurse leaders enabling nurses to adopt digital health: Results of an integrative literature review. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 38(3). https://doi.org/10.36951/001c.40333

Canada Health Infoway (2017, May). 2017 National survey of Canadian nurses: Use of digital Health technology in practice. Final executive report. https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/en/component/edocman/3320-2017-national-survey-of-canadian-nurses-use-of-digital-health-technology-in-practice/view-document?Itemid=0

Doctors of BC (2021). Lessons learned: Electronic health record engagement and implementation. https://facilityengagement.ca/sites/default/files/Lessons%20Learned%20-%20EHR%20Engagement%20%26%20Implementation.pdf

Donohue-Ryan, M. A., Peleg, N. A., Fochesto, D., & Kowalski, M. O. (2023). An organization’s documentation burden reduction initiative: A quality improvement project. Nursing Economic$, 41(4), 164–175.

Duffy, M. (2015). Nurses and the migration to electronic health records. The American Journal of Nursing, 115(12), 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000475294.12738.83

Evans R. S. (2016). Electronic health records: Then, now, and in the future. Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 25(S 01), S48–S61. https://doi.org/10.15265/IYS-2016-s006

Gesner, E., Gazarian, P., & Dykes, P. (2019). The burden and burnout in documenting patient care: An integrative literature review. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 264, 1194–1198. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190415

Heponiemi, T., Gluschkoff, K., Vehko, T., Kaihlanen, A. M., Saranto, K., Nissinen, S., Nadav, J., & Kujala, S. (2021). Electronic health record implementations and insufficient training endanger nurses’ well-being: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(12), e27096. https://doi.org/10.2196/27096

Kellogg, K. M., Fairbanks, R. J., & Ratwani, R. M. (2017). EHR usability: Get it right from the start. Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology, 51(3), 197–199. https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-51.3.197

Kinnunen, U., Heponiemi, T., Rajalahti, E., Ahonen, O., Korhonen, T., & Hyppönen, H. (2019). Factors related to health informatics competencies for nurses—Results of a national electronic health record survey. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 37(8), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000000511

Kirkpatrick Partners (2024). The Kirkpatrick Model. https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/the-kirkpatrick-model/

Kleib, M., Nagle, L. M., Furlong, K. E., Paul, P., Wisnesky, U. D., & Ali, S. (2022). Are future nurses ready for digital health? Nurse Educator, 47(5), E98–E104. https://doi.org/10.1097/nne.0000000000001199

Koukourikos, K., Tsaloglidou, A., Kourkouta, L., Papathanasiou, I. V., Iliadis, C., Fratzana, A., & Panagiotou, A. (2021). Simulation in clinical nursing education. Acta Informatica Medica, 29(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.5455/aim.2021.29.15-20

Kurt, S. (2018, September 6). Kirkpatrick model: Four levels of learning evaluation. Educational Technology. https://educationaltechnology.net/kirkpatrick-model-four-levels-learning-evaluation/

Lentz Maidment, K. (2024). Making tech-savviness mandatory in Canadian nursing. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 19(1). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=12749

Malane, E. A., Richardson, C., Burke, K. G. (2019). A novel approach to electronic nursing documentation education: Ambassador of learning program. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development 35(6), 324-329. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000587

McBride, S., Alexander, G. L., Baernholdt, M., Vugrin, M., & Epstein, B. (2023). Scoping review: Positive and negative impact of technology on clinicians. Nursing Outlook, 71(2), 101918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2023.101918

McBride, S., & Tietze, M. (2023). Calling for bold action to address the negative impact of technology on nurses. Texas Nursing, 967(4), 14–16. https://issuu.com/texasnurses/docs/tn-issue4-2023-digital

Menachemi, N., & Collum, T. H. (2011). Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 4, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S12985

Ministry of Health Services BC (2009, February). eHealth overview. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/about-bc-s-health-care-system/ehealth/ehealth_snapshot_february_2009_final_draft.pdf

Mohan, V., Garrison, C., & Gold, J. A. (2021). Using a new model of electronic health record training to reduce physician burnout: A plan for action. JMIR Medical Informatics, 9(9), e29374. https://doi.org/10.2196/29374

National Learning Consortium (2013). Change management in EHR implementation. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/resources/changemanagementprimer_feb2014.pdf

Olley, R., & Hozynka, J. (2023). The effectiveness of scenario-based training of clinicians in the use of electronic health records – A systematic literature review. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.24083/apjhm.v18i1.1711

Rouleau, G., Gagnon, M., Côté, J., Payne-Gagnon, J., Hudson, E., Dubois, C., & Bouix-Picasso, J. (2019). Effects of e-learning in a continuing education context on nursing care: Systematic review of systematic qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-studies reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(10), e15118. https://doi.org/10.2196/15118

Roumeliotis, N., Parisien, G., Charette, S., Arpin, E., Brunet, F., & Jouvet, P. (2018). Reorganizing care with the implementation of electronic medical records: A time-motion study in the PICU. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 19(4), e172-e179. https://doi.org/10. 1097/PCC.0000000000001450

Rousseau, D. M., & ten Have, S. (2022). Evidence-based change management. Organizational Dynamics, 51(3), 100899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2022.100899

Rucci, J. M., Ball, S., Brunner, J., Moldestad, M., Cutrona, S. L., Sayre, G., & Rinne, S. (2023). “Like one long battle:” Employee perspectives of the simultaneous impact of COVID-19 and an electronic health record transition. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 38(4), 1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08284-3

Samadbeik, M., Fatehi, F., Braunstein, M., Barry, B., Saremian, M., Kalhor, F., & Edirippulige, S. (2020). Education and training on electronic medical records (EMRs) for health care professionals and students: A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 142, 104238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104238

Scandiffio, J., Zhang, M., Karsan, I., Charow, R., Anderson, M., Salhia, M., & Wiljer, D. (2024). The role of mentoring and coaching of healthcare professionals for digital technology adoption and implementation: A scoping review. Digital Health, 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076241238075

Smailes, P. S., Zurmehly, J., Schubert, C., Loversidge, J. M., & Sinnott, L. T. (2019). An electronic medical record training conversion for onboarding inpatient nurses. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 37(8), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000000514

Ting, J., Garnett, A., & Donelle, L. (2021). Nursing education and training on electronic health record systems: An integrative review. Nurse Education in Practice, 55, 103168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103168

Topaz, M., Ronquillo, C., Peltonen, L. M., Pruinelli, L., Sarmiento, R. F., Badger, M. K., Ali, S., Lewis, A., Georgsson, M., Jeon, E., Tayaben, J. L., Kuo, C. H., Islam, T., Sommer, J., Jung, H., Eler, G. J., Alhuwail, D., & Lee, Y. L. (2017). Nurse informaticians report low satisfaction and multi-level concerns with electronic health records: Results from an international survey. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings. AMIA Symposium, 2016, 2016–2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5333337/pdf/2499455.pdf

Tsarfati, B., & Cojocaru, D. (2022). The importance of receiving training in computerized technology for nurses to maintain sustainability in the health system. Sustainability, 14(23). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315958

Vlerick, I., Kinnaer, L., Delbaere, B., Coolbrandt, A., Decoene, E., Thomas, L., Vanderlinde, R., & Van, H. A. (2024). Characteristics and effectiveness of mentoring programmes for specialized and advanced practice nurses: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 80(7), 2690–2714. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16023

Vuk, J., Anders, M. E., Mercado, C. C., Kennedy, R. L., Casella, J., & Steelman, S. C. (2015). Impact of simulation training on self-efficacy of outpatient health care providers to use electronic health records. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 84(6), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.02.003

Weinschreider, J., Sisk, H., & Jungquist, C. (2022). Electronic health record knowledge, skills, and attitudes among newly graduated Nurses: A scoping review. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 53(11), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20221006-08

Weinschreider, J., Tenzek, K., Foltz-Ramos, K., Jungquist, C., & Livingston, J. A. (2024). Electronic health record competency in graduate nurses: A grounded theory study. Nurse Education Today, 132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105987

Wilbanks, B. A., Watts, P. I., & Epps, C. A. (2018). Electronic health records in simulation education. Simulation in Healthcare, 13(4), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1097/sih.0000000000000288

Wilbanks, B. A., & Aroke, E. N. (2020). Using clinical simulations to train healthcare professionals to use electronic health records. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 38(11), 551–561. https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000000631

Younge, V. L., Borycki, E. M., Fellow, A. W. K., C. (2015). On-the-job training of health professionals for electronic health record and electronic medical record use: A scoping review. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, 7(3), 436–469. https://www.kmel-journal.org/ojs/index.php/online-publication/article/view/296

Biographical Statement

Jennifer Wilks holds a Master of Health Studies from Athabasca University, and a Bachelor of Arts from Simon Fraser University. She has been an education manager at a BC health authority for four years. She is passionate about furthering best practices in continuing education in the health sector.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Julia Lukewich, RN, PhD for her valuable insights throughout the process of writing this paper, and Sarah Manley, MHS and Jill Smith, MHS for their ideas, advice, and support.