Impact of Telehospice During the COVID-19 Pandemic

by April Casabona, RN, MSN

Jonah Abordo, RN, MSN

Geraldine Resonable, RN, MSN

Roison Andro Narvaez, RN, MSN, PhD (c)

Corresponding author

St. Paul University Philippines

Citation: Casabona, A., Abordo, J., Resonable, G., & Narvaez, R. A. (2025). Impact of telehospice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 20(2). https://cjni.net/journal/?p=14807

Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted traditional end-of-life care, prompting innovative solutions to maintain continuity and quality. Telehospice emerged as a key alternative, using virtual platforms to deliver hospice and palliative services while respecting social distancing measures.

Aim: This integrative review synthesizes evidence on the feasibility, effectiveness, and challenges of telehospice during COVID-19, with attention to patient outcomes.

Design: A systematic search identified 12 peer-reviewed studies published from January 2020 to June 2023 in databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Embase, and CINAHL.

Results: Telehospice improved access to care for patients in remote and underserved areas, offered rapid symptom management, and supported interdisciplinary collaboration. Family caregivers generally reported positive experiences and reduced travel burdens. Yet, barriers included limited technology, privacy concerns, and challenges replicating in-person interactions virtually.

Conclusion: Telehospice proved viable and acceptable for end-of-life care, although technical and training gaps remain. Strengthening digital infrastructure, privacy safeguards, and staff training can help integrate telehospice into standard practice.

Implications: Policymakers and healthcare systems should invest in virtual care capabilities and guidelines for telehospice to ensure equitable, patient-centred end-of-life services that extend beyond pandemic conditions. Going forward, comparing cost-effectiveness with conventional hospice approaches could further validate telehospice as an option for widespread adoption.

Highlights

What is already known about this topic

- Telehospice leverages virtual platforms to deliver hospice and palliative care from a distance.

- Before the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread adoption remained minimal due to reimbursement barriers and limited technological infrastructure.

- Pandemic-related constraints rapidly accelerated telehospice acceptance, revealing significant benefits alongside persistent implementation challenges.

What this paper adds

- Many families described telehospice as surprisingly comforting, offering real-time support and shared decision-making—even when physically separated.

- With reduced travel times and virtual visits, hospice nurses reported more frequent check-ins and quicker interventions for patient concerns.

- Acceptance of telehospice grew over time as both caregivers and clinicians adapted to virtual platforms, revealing the potential for long-term integration beyond pandemic conditions.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to healthcare systems worldwide, particularly in end-of-life care. Hospice care focuses on providing a peaceful and comfortable experience for patients nearing the end of life, separate from curative treatments (Shalev et al., 2017). The pandemic’s physical distancing and risks to vulnerable populations required innovative approaches to ensure continuous support and quality hospice care for patients with life-limiting illness. To address this, telehospice rapidly emerged as a significant trend in healthcare. Telehospice involves providing hospice care remotely using telehealth technologies, such as smartphones, tablets and laptops. This approach overcomes barriers to delivering high-quality end-of-life care by using low-cost electronic devices for clinical and educational devices (Ellis & Lindley, 2020).

Numerous studies have explored the impact of telehospice during the COVID-19 pandemic, shedding light on its relevance, issues, objectives, and contributions. The studies focused on the impact of telehospice during the COVID-19 pandemic hold crucial relevance in addressing the urgent need for alternative approaches to end-of-life care. With physical distancing measures limiting in-person interactions, telehospice has become an essential tool for healthcare providers to bridge the gap between patients, families, and palliative care specialists (Cameron et al., 2021). This study investigates the effectiveness and feasibility of implementing telehealth consultations as a means to ensure continuous support, enhance patient care, and address the unique challenges posed by the pandemic (Montoya et al., 2022).

The rapid adoption of telehospice services during the COVID-19 pandemic signifies a growing trend in healthcare delivery. This trend underscores the increasing recognition of telehospice as a viable solution to overcome physical barriers and improve access to telemedicine services (Whitten et al., 2005). With the utilisation of telehospice, healthcare provider teams were able to do virtual assessments and provide urgent patient care without the delay of travel time, especially during the height of the pandemic. The effectiveness of virtual care centres depends on being able to observe the patient while evaluating their clinical status. While the virtual consultation is not meant to replace traditional consultation, it can be sufficient to address some other medical concerns (Koziatek et al., 2020).

Exploring the impact of telehospice during the COVID-19 pandemic addresses several key issues. These include technical challenges associated with connectivity and video platforms, the limitations of remote assessments compared to in-person interactions, and the need for training and support to ensure efficient utilisation of telehospice services. Understanding these issues are vital for healthcare providers and policymakers to effectively navigate and optimise telehospice implementation, thereby enhancing the overall care experience for patients and families (Etkind et al., 2020).

This review aims to gain a better understanding of the impact of telehospice services during the COVID-19 pandemic. It examines the impact of telehospice in assessing patient outcomes, evaluating the feasibility and effectiveness of telehospice consultation, identifying challenges and opportunities, and exploring the experiences of patients and their families with telehospice. Through rigorous research and analysis, selected studies contribute valuable insights into the impact and potential of telehospice, informing healthcare practices, policy development, and future research in the field (Webb et al., 2021). The impact of telehospice during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a subject of extensive investigation by numerous studies. However, there is no extensive review of the impact and roles performed by clinicians such as nursing personnel during telehospice consultation. By exploring its relevance, trends, key issues, objectives, and contributions, these studies provide a comprehensive understanding of the value of telehospice consultations in overcoming the challenges posed by the pandemic. The insights garnered from these reviewed studies serve as a foundation for enhancing patient care, improving access to palliative services, and shaping the future of telehospice in the post-pandemic era.

Method

Design

This is an integrative review of relevant literature to consolidate and analyze existing knowledge on telehospice’s impact during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings may enrich our understanding and guide future research in telehospice and remote healthcare. It may also reveal ways to refine telehospice practices and develop strategies for effective use in future public health emergencies or whenever in-person care is constrained. The process for an integrative review (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005) includes:

- Identifying the problem

- Searching the literature

- Evaluating the gathered data

- Data analysis

- Presentation of findings and summarizing existing literature, generating insights for further study

Search Strategy

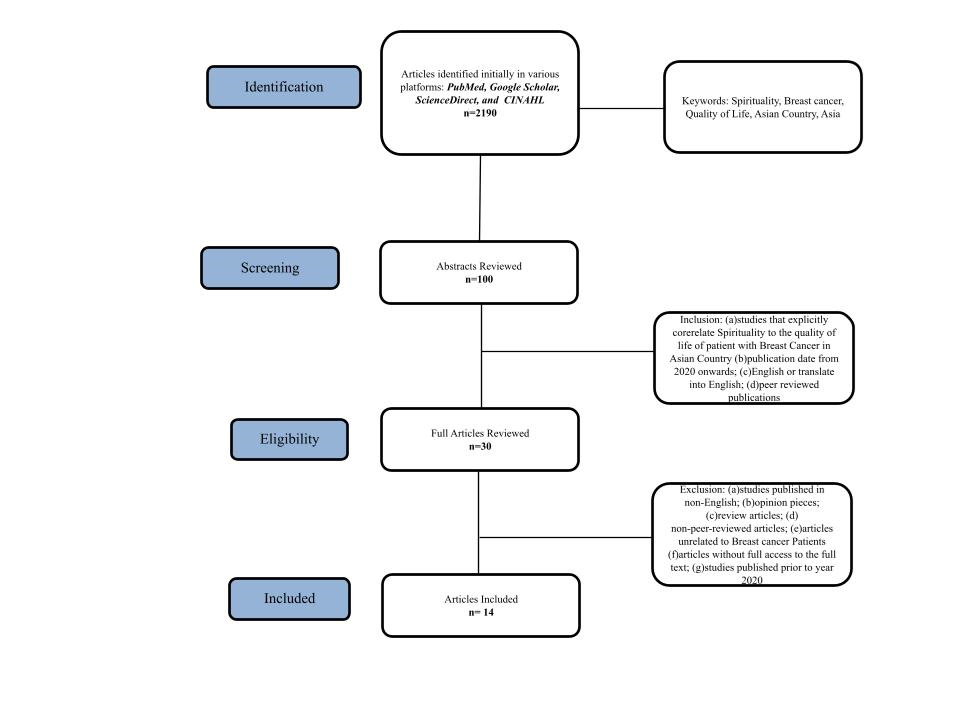

A comprehensive search was conducted from May to June 2023 across five electronic databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Embase, and CINAHL. The search utilized key terms such as “telehospice,” “telemedicine,” “COVID-19,” “pandemic,” and “hospice care,” combined with Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to ensure specificity and sensitivity of results. Truncation (e.g., telehosp*) and wildcard symbols were applied to capture variations in terminology. For instance, searches paired “telehospice” with “palliative care” or “virtual consultations” to encompass diverse expressions of remote end-of-life care. References within relevant studies were also hand-searched for additional sources. Following the initial retrieval of 751 articles, titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria. After removing duplicates and studies with incomplete or irrelevant data, 25 full-text articles underwent a detailed review, ultimately yielding 12 articles that met all eligibility requirements. This systematic approach minimized the risk of overlooking pertinent literature and strengthened the review’s reliability (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This review included peer-reviewed studies published between January 2020 and June 2023, in English or translated into English, and directly focused on telehospice or remote hospice care. Studies were excluded if they were non-English without translation, did not provide full-text access, were opinion pieces or secondary sources, addressed telehealth without a telehospice component, or were published before 2020. This ensured a contemporary, high-quality dataset on telehospice services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Evaluation/ Quality Appraisal

Data were extracted into a standardized table based on Sparbel and Anderson’s work (2000), capturing each study’s authors, publication year, country, design, sample size, instruments, aims, main findings, level of evidence, and key themes (Table 1). The review then applied Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt’s (2019) evidence hierarchy to assess methodological rigor, risk of bias, and overall quality. Any discrepancies in study inclusion or assessment were resolved through discussion and consensus. This approach ensured that only robust, high-quality research informed the review’s conclusions.

Results

Characteristics of the Study

As shown in Table 1, twelve research articles published between 2020 and 2023 were reviewed and synthesized for inclusion in this integrative review. The research was conducted in various countries including the United States of America (n=7), Canada (n=1), Taiwan (n=1), Scotland (n=1) and Italy (n=2). The research designs utilized included one cohort study, one cross-sectional study, two case series, four qualitative studies, two quantitative studies, one quasi-experimental study, and one mixed-method study. Nine of the studies provided Level VI evidence, two showed Level IV evidence and one had Level III Evidence. The studies involved a total of 22,442 participants, including patients, family members, caregivers, and a hospice care provider who had experience with telehospice during the COVID-19 Pandemic. From the 12 included studies, two were based on the patient perspective, nine were based on the care provider perspective (clinicians, nurses, caregivers, hospice personnel), and one was based on both the patient and care provider perspectives.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies on The Impact of Telehospice During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The selected studies employed a variety of methods and instruments, including the sample t-test, Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS 7–12), PedsQL Family Impact Module (PedsQL FIM), survey questionnaires, voice-recorded interviews, telephone surveys, focus groups, and quantitative analyses. The findings highlighted the positive impact of telehospice interventions on patient outcomes, their feasibility and effectiveness, as well as associated challenges, opportunities, and beneficial experiences reported by patients and families.

Aim of the studies

Based on the overall findings of the selected studies examining the effects of telehospice during the COVID-19 pandemic, the study aims can be synthesized into the following overarching themes. Firstly, they evaluated patient outcomes through telehospice interventions, including symptom reduction, overall well-being, and quality of life, as well as mental health outcomes like anxiety and depression. (Weaver et al., 2020; Weaver et al., 2021; Chou et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Mercadente et al., 2020). They also explored patient and family satisfaction with telehospice services. (Lewis et al., 2020; Mercadente et al., 2020) Secondly, the studies assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of telehospice consultations, focusing on accessibility, efficiency, resource utilization, and the delivery of essential healthcare services. (Chou et al., 2020; Weaver et al., 2020a; Ellis & Lindley, 2020; Cameron et al., 2020; Weaver et al., 2020b) Additionally, they investigated the impact on healthcare providers, such as workload and job satisfaction.

Challenges and Opportunities

Four studies identified challenges and barriers in implementing telehospice services, such as technological limitations, internet connectivity issues, and privacy concerns (Elma et al., 2022; Ellis & Lindley, 2020; Schinasi et al., 2021; Cameron et al., 2020). They also explored the opportunities and advantages of telehospice, including increased accessibility to specialized care, reduced travel burden for patients and families, and the potential for improved interdisciplinary collaboration. These studies also investigated the impact of telehospice on healthcare systems and policy development, including its role in shaping future healthcare practices and resource allocation.

Discussion

The included studies underscored the critical role that telehospice played in delivering end-of-life care during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically in addressing barriers created by social distancing measures. Most investigations reported positive patient outcomes, including enhanced symptom management, improved psychological well-being, and reduced travel burdens (Weaver et al., 2020b; Weaver et al., 2021c). Despite methodological variability across the studies (e.g., differing designs, sample sizes, and instruments), the overwhelming consensus pointed toward telehospice’s feasibility and acceptability. Notably, children and adult patients receiving remote hospice support often expressed feeling “remembered” and well-informed, highlighting telehospice’s capacity to preserve a sense of connectedness in palliative care (Weaver et al., 2020b).

A second overarching theme concerns the feasibility and effectiveness of telehospice services in extending access to quality care. Researchers observed that telehospice expanded care beyond geographical constraints, which especially benefited rural populations (Weaver et al., 2020a; Weaver et al., 2021c). The speed of the consultation process—unburdened by in-person travel—proved particularly valuable in urgent or time-sensitive situations, enabling nurses to respond swiftly to patient and family needs (Cameron & Gugala, 2020). However, these successes hinged upon reliable technology and sufficient training for both patients and clinicians. In instances where technical infrastructure or digital literacy was lacking, engagement with telehospice services proved more challenging (Ellis & Lindley, 2020).

Concurrently, some of the studies highlighted various practical and ethical challenges. Chief among them were technology barriers such as weak internet signals, connectivity limitations, and user inexperience, all of which occasionally led to misinterpretations of clinical conditions (Weaver et al., 2020a; Elma et al., 2022). The inability to replicate certain in-person nuances—touch, facial expressions, or environmental cues—also raised concerns about the authenticity and warmth of virtual interactions (Elma et al., 2022). Privacy and security considerations emerged as an additional concern, as providers adapted to new telecommunication platforms with variable adherence to confidentiality regulations (Schinasi et al., 2021).

Despite these hurdles, many family caregivers appreciated telehospice for its convenience and the immediate support it facilitated (Mercadente et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2020). Caregivers caring for terminally ill patients highlighted the value of shared decision-making and prompt goal-of-care discussions, even when they could not be physically present with their loved ones (Mercadente et al., 2020). This was particularly salient in scenarios where hospitals or hospice facilities imposed strict visitation restrictions during COVID-19. Recognizing this value, several authors recommended a hybrid approach—integrating remote telehospice consultations with occasional in-person visits to balance comprehensive assessment and rapport-building (Lin et al., 2022).

Looking ahead, the studies collectively indicated that telehospice is likely to remain a vital component of end-of-life care, particularly when geographic or policy-driven constraints limit face-to-face interactions. Future research might focus on determining best practices for training hospice staff in virtual communication and assessment, refining secure telehealth platforms to safeguard patient privacy, and exploring cost-effectiveness comparisons between telehospice and traditional hospice (Chou et al., 2020; Cameron & Munyan, 2021). As governments and healthcare organizations contemplate embedding telehospice more deeply into their care models, these findings can inform policies that foster equitable technology access, bolster interdisciplinary collaboration, and ultimately improve palliative care experiences for patients and families in need.

Implications for Practice

Telehospice has the potential to transform palliative care by enabling continuous support, rapid consultations, and family involvement regardless of geographic barriers. Nurses and other hospice professionals can leverage telehospice to promptly address patient symptoms, offer emotional support, and collaborate with interdisciplinary teams in real time. Moreover, virtual platforms allow for ongoing caregiver education—equipping family members with skills and confidence to participate more actively in care. With appropriate training, healthcare providers can refine telehospice communication strategies, conduct nuanced remote assessments, and offer individualized patient counseling. Over the long term, policy integration and financial investment in telehospice infrastructure can further enhance its reach, ensuring sustainable and equitable access to end-of-life services.

Limitations and Recommendations

A key limitation is that most existing studies focus on high-income countries with comparatively robust technological infrastructures, potentially limiting the generalizability of telehospice across resource-limited settings. Additionally, many reviews, including this one, are bound by English-language publications, raising the possibility of language bias. Future research should include multilingual and multi-regional perspectives to capture a more global picture of telehospice effectiveness. Studies could also adopt longitudinal designs to assess the durability of telehospice outcomes and cost-effectiveness relative to traditional care. Lastly, standardizing security and privacy protocols would help address ethical considerations and build patient confidence in telehospice interactions. By incorporating these recommendations, telehospice can continue evolving as a vital component of end-of-life care, during and beyond public health crises.

Conclusion

Telehospice proved crucial in sustaining access to end-of-life care during the pandemic, bridging physical gaps and reducing the need for in-person visits. Feedback from patients, caregivers, and providers largely affirmed its adaptability and acceptability, despite technological and privacy-related challenges. With continued investment in infrastructure, broader training, and stronger policy support, telehospice can remain equitable, sustainable, and responsive to future healthcare needs. Its evolving role promises to reshape how end-of-life care is delivered, extending benefits well beyond pandemic constraints.

References

Cameron, P. M., & Gugala, K. (2020). Virtual visits in hospice: Lessons learned and directions for the future (FR441D). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 59(2), 471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.12.156

Cameron, P. M., & Munyan, K. (2021). Systematic review of telehospice, telemedicine and e-Health. Telemedicine and e-Health, 27(11), 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0451

Chou, Y., Yen, Y., Feng, R., Wu, M., Lee, Y., Chu, D., Huang, S., Curtis, J. R., & Hu, H. Y. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the utilization of hospice care services: A cohort study in Taiwan. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(3), e1–e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.07.005

Costantini, M., Sleeman, K. E., Peruselli, C., & Higginson, I. J. (2020). Response and role of palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national telephone survey of hospices in Italy. Palliative Medicine, 34(7), 889–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320920780

Elma, A., Cook, D. J., Howard, M., Cook, D. J., Hoad, N., Swinton, M., Clarke, F. D. A., MD, Rudkowski, J. C., Boyle, A., Dennis, B. B., Vegas, D. B., & Vanstone, M. (2022). Use of video technology in end-of-life care for hospitalized patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Critical Care, 31(3), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2022722

Ellis, K. S., & Lindley, L. C. (2020). A virtual children’s hospice in response to COVID-19: The Scottish experience. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(2), e40–e43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.011

Etkind, S. N., Bone, A. E., Lovell, N., Cripps, R. L., Harding, R., Higginson, I. J., & Sleeman, K. E. (2020). The role and response of palliative cre and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: A rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), e31–e40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029

Koziatek, C. A., Rubin, A., Lakdawala, V., Lee, D. J., Swartz, J., Auld, E., Smith, S. W., Reddy, H., Jamin, C., Testa, P. A., Femia, R., & Caspers, C. (2020). Assessing the impact of a rapidly scaled virtual urgent care in New York City during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 59(4), 610–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.06.041

Lewis, F. M., Loggers, E. T., Phillips, F., Palacios, R., Tercyak, K. P., Griffith, K. A., Shands, M. E., Zahlis, E. H., Alzawad, Z., & Almulla, H. A. (2020). Enhancing connections-palliative care: A quasi-experimental pilot feasibility study of a cancer parenting program. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(2), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0163

Lin, S., Jones, T., David, D., Lassell, R., Durga, A., Convery, K., Ford, A., & Brody, A. A. (2022). Supporting dementia family care partners during COVID-19: Perspectives from hospice staff. Geriatric Nursing, 47, 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.08.003

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. (Fourth edition). Wolters Kluwer.

Mercadante, S., Adile, C., Ferrera, P., Giuliana, F., Terruso, L., & Piccione, T. (2020). Palliative care in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(2), e79-e80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.025

Montoya, M. I., Kogan, C. S., Rebello, T. J., Sadowska, K., Garcia-Pacheco, J. A., Khoury, B., Kulygina, M., Matsumoto, C., Robles, R., Huang, J., Andrews, H. F., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Denny, K., Gaebel, W., Gureje, O., Kanba, S., Maré, K., Medina-Mora, M. E., Pike, K. M., Roberts, M. C., … Reed, G. M. (2022). An international survey examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on telehealth use among mental health professionals. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 148, 188-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.050

Schenker, Y., Kavalieratos, D., Gryczynski, J., & Patel, S. (2020). Feasibility of video consultations for outpatient palliative care home visits: Cross-sectional observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e16684. https://doi.org/10.2196/16684

Shalev, A., Phongtankuel, V., Kozlov, E., Shen, M. J., Adelman, R. D., & Reid, M. M. (2017). Awareness and misperceptions of hospice and palliative care: A population-based survey study. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 35(3), 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117715215

Schinasi, D. A., Foster, C. C., Bohling, M. K., Barrera, L., & Macy, M. L. (2021). Attitudes and perceptions of telemedicine in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of naïve healthcare providers. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 647937. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.647937

Sparbel, K. J., & Anderson, M. A. (2000). Integrated literature review of continuity of care: Part 1, conceptual issues. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32(1), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00017.x

Weaver, M. S., Neumann, M. L., Navaneethan, H., Robinson, J. T., & Hinds, P. S. (2020a). Human touch via touchscreen: Rural nurses’ experiential perspectives on telehealth use in pediatric hospice care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(5), 1027–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.003

Weaver, M. S., Robinson, J. T., Shostrom, V., & Hinds, P. S. (2020b). Telehealth acceptability for children, family, and adult hospice nurses when integrating the pediatric palliative inpatient provider during sequential rural home hospice visits. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(5), 641–649. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0450

Weaver, M. S., Shostrom, V., Neumann, M. L., Robinson, J. T., & Hinds, P. S. (2021c). Homestead together: Pediatric palliative care telehealth support for rural children with cancer during home?based end?of?life care. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 68(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28921

Webb, M., Hurley, S. L., Gentry, J., Brown, M., & Ayoub, C. (2021). Best practices for using telehealth in hospice and palliative care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing : JHPN : the official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 23(3), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000753

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. A. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Whitten, P., Doolittle, G., & Mackert, M. (2005). Providers’ acceptance of telehospice. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 8(4), 730-735. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2005.8.730

Author Bio(s)

April Casabona, RN, MSN https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3518-5805

Jonah Abordo, RN, MSN https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1706-5590

Geraldine Resonable, RN, MSN https://orcid.org/0009-0005-9822-8891

Roison Andro Narvaez, RN, MSN, PhD (c) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7555-5420

St. Paul University Philippines