The Views of Nurse Practitioner Students on the value of Personal Digital Assistants in clinical practice

by Kimberley Lamarche, RN NP DNP

and Caroline Park, RN PhD

Athabasca University

Abstract

![]() Hand held technology has been evolving and has played an integral role in supporting point of care decision making in health care. There has been substantive research on the use of mobile devices in medical and nursing practice, but much less in nursing education. Efforts to introduce mobile technology to novice or intimidated users have helped introduce Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) into Nurse Practitioner (NP) practice. The purpose of this study was to ascertain the number of nurse practitioner students who actually use PDAs, the specific clinical programs they find useful, and the perceived barriers to utilizing PDA technology. Two short surveys were developed; one for those students who owned PDAs and another for those who did not. One hundred and fifty students responded, including 64 students who did use a PDA and 86 who did not. Respondents were baccalaureate prepared Masters level NP students with at least two years of experience as registered nurses.

Hand held technology has been evolving and has played an integral role in supporting point of care decision making in health care. There has been substantive research on the use of mobile devices in medical and nursing practice, but much less in nursing education. Efforts to introduce mobile technology to novice or intimidated users have helped introduce Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) into Nurse Practitioner (NP) practice. The purpose of this study was to ascertain the number of nurse practitioner students who actually use PDAs, the specific clinical programs they find useful, and the perceived barriers to utilizing PDA technology. Two short surveys were developed; one for those students who owned PDAs and another for those who did not. One hundred and fifty students responded, including 64 students who did use a PDA and 86 who did not. Respondents were baccalaureate prepared Masters level NP students with at least two years of experience as registered nurses.

Study findings are aligned with anecdotal and published information on the use of PDAs and provide academics with valuable insight into the practice experiences at the “point of care”. Following this study, our institution implemented a policy making mobile devices a mandatory requirement for all NP students registered in the program. The study results informed the program policy, provided essential information about specific software, and helped develop recommendations for nursing education.

Introduction

Society and nursing are both evolving at an alarming pace. Advances in patient acuity level, health care technology and policy have impacted management of patient care. Hand held technology has surfaced as an integral tool to support decision making at the point of care. A 2009 online poll by Ipsos Reid revealed that seventy per cent of Canadians use mobile phones for personal e-mail and more than one quarter browse the web from their mobiles at least daily. It is important that we understand the impact of these devices on communication and information-seeking, and how they can be used to enhance teaching, learning and clinical practice in nursing. Hand held devices such as personal digital assistants (PDAs) are beginning to replace hard bound books that are traditionally used at the bedside. Certainly, many Canadian post-secondary students use smart phones, 3G phones or other mobile devices in daily life. Nurse Practitioners (NPs) are no exception to this trend as they transition to the digital age.

Literature Overview

Research and knowledge is still emerging on how mobile communication devices influence and contribute to Canadian. The widespread adoption of mobile wireless technology in the form of cell phones, PDAs, laptop computers, and MP3 players is now irrefutable (Keegan, 2005; Wagner, 2005). Current mobile technologies – especially third and fourth generation (such as 3G & 4G) wireless devices such as the Apple iPhone and Google Android cell phone – provide an unprecedented opportunity for inexpensive and beneficial computing power for learners (Hill & Roldan, 2005; Wagner, 2005).

While there has been substantive research on the use of mobile devices in medical and nursing practice, much less is known about their application in nursing education. Research designs used to study medical professionals and PDAs tend to be surveys of those adopting the technology (Chatterly & Chorecki, 2010; Dasgupta et al., 2010); opinion papers such as literature reviews have also surfaced (Ruskin, 2010). Researchers who have studied nurses’ use of PDAs have mainly focused on device usability and resource use (Brubaker et al., 2009; Cahoon, 2002; Newbolt, 2003; Rosenthal, 2003) and findings show that nurses are early adopters of PDAs for information support. The PDAs have been used as reference for drug interactions and laboratory values and to email pharmacy and laboratory requisitions. Nurse educators have used mobile devices to keep records of student assignments, form checklists for physical assessments, a source for information at the point-of-care, and to document student progress on-the-spot (Lehman, 2003). Goldsworthy, Lawrence and Goodman (2006) reported greater self-efficacy in administering medications among students who used PDAs; Miller et al. (2005) found students who used PDAs posed more questions in the practice setting and demonstrated a greater need for current resources. Mackay (2006) found that the use of Short Message Service (SMS) text messaging fostered a sense of connectivity with her students and supported a theory about planned mobile interaction between faculty and clinical students. Wyatt et al (2010) noted that, although researchers have mainly reported benefits including student belief that PDAs improve the quality of patient care through enhanced access to drug and lab information. Despite these benefits, few experts have reported integration of PDA technology into nursing education curriculum.

During the 2000s, experts began to report the potential uses, advantages, and barriers to the use of PDAs among nurse practitioners (Keeling, Snyder, Wyatt, Krauskopf, 2003; Bower, 2004; Newbolt, 2004). Review of the literature indicates that the transition to PDA use has not been seamless. Targeted efforts to introduce mobile technology to the novice or intimidated user have assisted with the introduction of the PDAs into NP practice (Rempher, Lamsone & Lamsone, 2003). Experts have described NP phobias towards PDAs and how planned PDA instructions for new, intermediate and advanced nurses (Krauskopf, 2006) have assisted in the education of point of care clinicians.

Of special note in the literature is the usefulness of mobile technology. Krauskopt & Farrell (2011) discovered a significant interaction and difference in accuracy in the laboratory analysis section of case scenarios (F (1,38) = 21.256, p? .001) in the PDA group when compared with the textbook group of 40 novice NPs. These findings acknowledge that PDA use has benefits for novice practitioners in evaluation of clinical situations; benefits were revealed for both gaining access to correct information and doing so in a timely manner (Krawskopt & Farrell, 2011). Likewise in a study of nursing students, Goldworthy (2006) reported a significant increase in medication administration self-efficacy among students who used the PDA.

Current literature supports the integration of mobile technology into Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) education (Krawskopt & Farrel, 2011; Williams & Dittmen, 2009; Wyatt, 2010). A Canadian survey of NPs and Clinical Nurse Specialists identified improved client care as the major benefit of this technology in practice. The type and range of tools used by these nurse professionals included clinical reference tools, such as drug and diagnostic/laboratory reference applications, and wireless communication devices (Garrett & Klein, 2010).

Anecdotally reports by students have suggested widespread use of PDAs by students, preceptors and clinical sites. This anecdotal evidence however does not assist program planners as they develop policy decisions about specific software, hardware, and mobile applications to require students to use. The current extent of knowledge in the literature is insufficient to drive policy change related to PDA use. The purpose of this study was to ascertain the number of nurse practitioner students who actually use PDAs, the specific clinical programs they find useful, and the perceived barriers to utilizing PDA technology.

Methods

A nonexperimental, descriptive survey research design was used, delivered via an online distance graduate NP program course. The online WebCT learning platform allowed quick mobilization of the quiz feature to collect responses from both the PDA users and non-users and their perceptions about PDAs. For data collection, the survey was loaded on the Program communication page. Ethical approval for the study was received from the university Research Ethics Board; students were advised that participation was voluntary and that the anonymous quiz was not linked to their course work.

The researchers wanted to collect perspectives from two groups of students: those who currently use and do not use PDAs. Therefore, two short surveys were developed to capture these two perspectives. An invitation to complete the voluntary survey was posted online to all NP students in clinical courses.

Participants

One hundred and fifty APN students registered in an NP program of an online institution responded. Respondents were baccalaureate prepared Masters level NP students with at least two years of experience as registered nurses. While no demographic information was collected, future research is planned to study whether age is related to perceived barriers. Of the one hundred and fifty respondents, sixty-four (42.6%) reported they did not use a PDA and 86 (57.3%) said they did.

Results

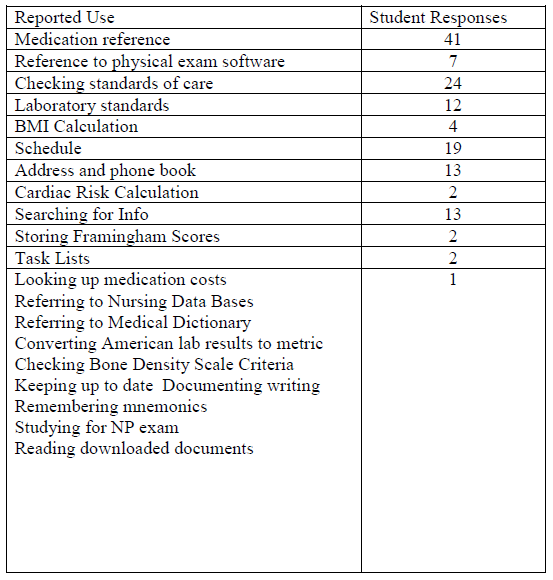

There were data to report on three main areas; student PDA use, student PDA barriers, and rationale for recommendation to other students. Descriptions of PDA use by the students in this study were similar to those mentioned in published reports. For example, the NP students reported PDA use for tasks such as: drug reference, lab values, calculator, calendar, and contact lists. Table 1 provides a snapshot of the students’ reported use, in their own words. For these students, “studying” was also reported as a PDA’s use. Studying via the PDA is definitely an implication for educational planners.

Table 1: APN Student Reported PDA Uses (N=82)

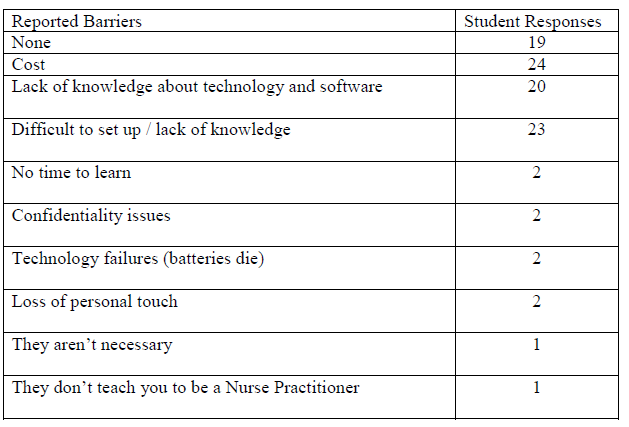

Students who reported no use of a PDA were asked about perceived barriers (Table 2). These perceptions are also relevant for educational planning to reduce perceived barriers, such as cost, confidentiality, technology failures, lack of knowledge, and loss of personal touch.

Table 2: APN Student Reported PDA Barriers (N=79)

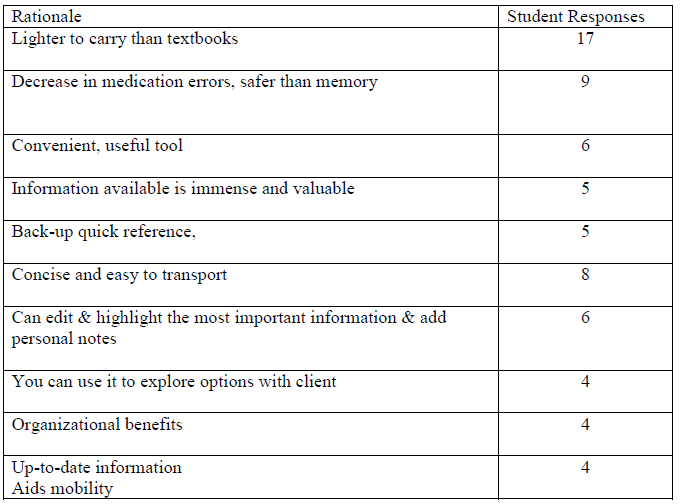

It was important to explore whether students would advise other students to use PDAs. To that end, those students who did not use a PDA were invited to answer the following question: would you recommend the use of PDAs to other NP students? If so why? Their responses (N=49) are reflected in Table 3. Many of these responses are predictable however the responses “the way of the future”, ” looks professional” and “you can use it to explore options with the clients” relate to professional identity and new ways to enhance practice. These quotes suggest that the potential power of this new technology goes beyond just being an assistive device and an informational support tool.

Table 3: APN Student Recommendation Rationale (N= 49)

At the time of the study, PDA ownership was optional for students in the NP program. Given the cost associated with a possible requirement of internet access for students, one survey question specifically asked about Internet connectivity. Only half of the users reported that their PDA supported Internet connectivity which is consistent with the report that the frequency of mentioning activities such as e-mail and web browsing were low.

Discussion

Based upon the experiences of other researchers (Davenport, 2004, Jones, Johnson &Bentley, 2004), cost and lack of computer ability were predictable barriers. Confidentiality issues or concerns are also cited, and paramount in any professional discipline. This is an issue that can be addressed through careful planning of the educational program. Students identified “lack of personal touch”, “they aren’t necessary” and “they don’t teach you to be an NP” as reasons not to use a PDA. These students need help to recognize that a PDA is one of the many tools available to practitioners. It is not likely that research would suggest that PDAs are critical for learning or for competent practice, but in this technological age, it is important to keep current with new applications to be informed of the options for point of care decision-making. Due to rapid change and introduction of new technologies, nurses in advanced practice must be aware of the latest possibilities. These last three barriers are more profound and address philosophical issues unrelated to funding or policy decisions and lead to interesting personal decision making. Educators can use knowledge of these barriers as teaching tools to explore students’ perceptions of about these electronic devices and their benefits to nursing practice.

Following this study, our institution implemented a policy making mobile devices a mandatory requirement for all NP students registered in the APN program. The study results informed the program policy, provided essential information about specific software, and helped develop recommendations from nursing education. NP students learn through practice with patients and contributions to the health care team. It is imperative that NPs are equipped with the most appropriate clinical tools to create successful practitioners and optimal patient care outcomes. The required software is now provided with course packages and includes electronic lab references and clinical management texts for students to load on the device of their choice. The option to log their clinical encounters on their PDA has increased efficiency during their clinical practicum and created rich information to guide the student progress. Overall the study results are consistent with both anecdotal and published information about PDA use and provide academics with valuable insight into the student practice experience at the “point of care”.

Conclusions

As PDA use grows, the value of reflection of learning and practice draws increased attention from policymakers and evaluators. Training and orientation to use of the handheld equipment and software applications should include assessment of systems connectivity and integration, access authority, existing skills, and previous use of devices. Proponents of PDA use to support clinical decisions should assure access to reliable, useful and accurate information to NPs for reflection on learning and practice.

Wyatt (2010) concluded that successful preparation of NP graduates requires skills necessary to function in the present and future health care system. NP faculty are required to be creative, and innovative, and to incorporate various revolutionary technologies into their nurse practitioner curricula. With the rapid turnover of health care information and the ongoing need for content revision, traditional textbooks may no longer serve as reliable, current resources for nursing. Therefore, nurse educators are challenged to select relevant resources and reliable handheld technology, or PDAs for teaching and learning. (Remoher et al, 2003). The results of this study, consistent with previous literature demonstrate show that nurse educators should embrace hand held technology as the way of the future.

References

Bower, N. (2004). Put technology at your fingertips with a PDA. Nurse Practitioner Journal, 29(2), 45-46.

Brubaker, C.L., Ruthman, J. & Walloch, J.A. (2009). The Usefulness of Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) to Nursing Students in the clinical setting. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(6), 390-392.

Cahoon, J. (2002, April). Handhelds in health care: Benefits of content at the point of care. Advances in Clinical Knowledge Management, 5. Retrieved from http://www.openclinical.org/docs/ext/workshops/ackm5/absCahoon.pdf

Chatterley, T. & Chojecki, D. (2010). Personal digital assistant usage among undergraduate medical students: Exploring trends, barriers, and the advent of smartphones. Journal of Medical Library Associations, 98(2), 160.

CNW Group. (2011). Mobile Adoption by Canadian Physicians: A Harbinger of Digital use at Patient Point-of-Care.

Dasgupta, A., Sansgiry, S. S., Sherer, J. T., Wallace, D., & Sikri, S. (2010). Pharmacists’ utilization and interest in usage of personal digital assistants in their professional responsibilities. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 27, 37–45.

Davenport, C. (2004). Analysis of PDAs in Nursing: Benefits and barriers. Retrieved from http://www.pdacortex.com/Analysis_PDAs_Nursing.htm

Garrett, B., Klein, G. (2008, August). Value of wireless personal digital assistants for practice: perceptions of advanced practice nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(16), 2146-54.

Hill, T. R. & Roldan, M. (2005). Toward third generation threaded discussions for mobile learning: Opportunities and challenges for ubiquitous collaborative learning environments.Information Systems Frontiers, 7(1), 55-70.

Ipsos Reid (2009, May). Two in ten (17%) cellphone and smartphone users typically access the internet on a daily basis from their phone. Commercial poll. Toronto: ON. Retrieved from http://www.ipsos-na.com/news/pressrelease.cfm?id=4398

Jones, C., Johnson, D. & Bentley, J. (2004). Role preference: Are handheld computers an educational or personal technology? Journal of Information Systems Education,15(1), 41-53.

Keeling, A., Snyder, A., Wyatt, T., Krauskopf, P. (2003). Accessing PDA information. Nursing Practitioner Journal, 28(1), 10.

Keegan, D. (2002). The future of learning: From eLearning to mLearning. Ericsson.

Keegan, D. (2005, October). The incorporation of mobile learning into mainstream education and training. Paper presented at mLearn 2005, the 4th World Conference on Mobile Learning. Cape Town, South Africa.

Krauskopf, P. B. & Farrell, S. (2011), Accuracy and Efficiency of Novice Nurse Practitioners Using Personal Digital Assistants. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43, 117–124.

Krauskopf, P., Wyatt, T. (2003). Even techno-phobic NPs can use PDAs.Nursing Practitioner Journal, 31(7), 48-52.

Lehman, K. (2003). Clinical nursing instructors’ use of handheld computers for student recordkeeping [Electronic version]. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(10), 41-42.

Mackay, B. (2007). Using SMS mobile technology to M-support nursing students in clinical placements. Nursing & Health Conference Papers. Retrieved from http://www.coda.ac.nz/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=northtec_nh_cp

Miller, J., Shaw-Kokot, J. R., Arnold, M. S., Boggin, T., Crowell, K. E., Allehri, F., et al. (2005).A study of personal digital assistants to enhance undergraduate clinical nursing education.Journal of Nursing Education, 44, 19-26.

Newbolt, S. K. (2003, October). New uses for wireless technology. Nursing Management, 22, 22-32.

Rempher, K., Lasome, C. & Lasome, T (2003). Leveraging palm technology in the advanced practice nursing environment. AACN Clinical Issues. 14(3), 363-70.

Rosenthal, K. (2003). “Touch” vs. “tech”: Valuing nursing specific PDA software. Nursing Management, 34(7), 58.

Ruskin, K. J. (2010). Mobile technologies for teaching and learning. International Anaesthesiology Clinics, 48(3), 53-60.

Stroud, S., Erkel, E. & Smith, C. (2005). The use of Personal Digital Assistants by Nurse Practitioner students and faculty,

Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 17(2), 67-75.

Wagner, E. D. (2005). Enabling mobile learning. Educause Review, 40(3), 40-53.

White, A., Allen, P., Goodwin, L., Breckenridge, D., Dowell, J.R. & Garvey, R. (2005). Nurse Educator 30(4): 150-154.

Williams, M. G., & Dittmen A. (2009).Textbook on tap: Using electronic books housed in handheld devices in nursing clinical courses. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(4), 220-225.

Wyatt, T. (2010). Cooperative M-learning with Nurse Practitioner Students Nursing Education Perspectives 31(2), 109-112.

Zurmehly, J. (2010). Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs): Review and Evaluation. Nursing Education Perspectives: 31(3), 179-182.

Author Bios

Caroline Park, R.N., Ph.D.

Caroline is an Associate Professor with the Centre for Nursing and Health Studies at Athabasca University, where she teaches in the Masters of Health Studies and the Masters of Nursing programs. Besides an interest in hand held devices for clinical learning, she is participating in research relating to inter-disciplinary research teams. Caroline can be reached at: clpark@athabascau.ca

Kimberley Lamarche, R.N., N.P., DNP

Kimberley is an Assistant Professor with the Centre for Nursing and Health Studies at Athabasca University, where she teaches in the Masters of Nursing program. Besides an interest in hand held devices for clinical learning, she is participating in research relating to Nurse Practitioners. Kimberley can be reached at: lamarche@athabascau.ca

CJNI Editors

- Dr. Loretta Secco

- Helen Edwards

- Elsie Duff